Poetic and one-drop magical, but also real: 'Ricantations' - An interview with Loretta Collins Klobah by Ann Margaret Lim

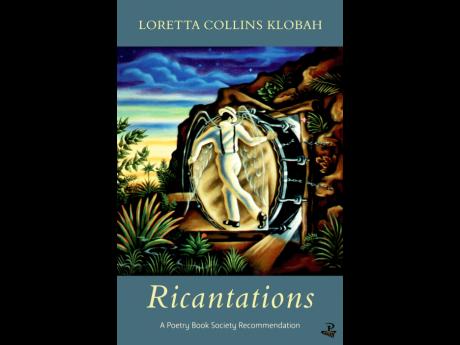

Loretta Collins' Klobah second book Ricantations (Peepal Tree Press, 2018) is a British Poetry Book Society summer recommendation. As her editor notes, this new book confirms and builds on Collins Klobah's reputation as a "superb poetic storyteller," which she earned from her first book, The Twelve-Foot Neon Woman (Peepal Tree). It received the 2012 OCM Bocas Award for Caribbean Literature in the category of poetry.

Ricantations chronicles moments from Puerto Rican history and the current circumstances of the island, giving readers vivid glimpses of coastal and mountain pueblos, where the mythic, the monstrous, and the marvellous elements of the society, as well as art and music, are invoked as a means of thinking through some of the urgencies of the past and the here-and-now. She stays close to her subject matter, writing compellingly (harshly or humorously) about the strangeness of everyday life, speaking out about damaging social forces and violence in the Caribbean context, engaging with the natural world, and painting poignant portraits of memorable people.

Collins Klobah recounts about Ricantations and her writing life as a poet, also touching on the previous book,The Twelve-Foot Neon Woman.

AML: As you did in your first book, The Twelve-Foot Neon Woman, in Ricantations, you have placed Puerto Rico squarely within the ambit of Caribbean poetry while endearing the people, stories, and places of Puerto Rico to those outside of that island. Your work challenges those who would try to exclude Puerto Rico from the Caribbean space. Is the placing of Puerto Rico as Caribbean something that you deliberately set out to do? Is that the aim, to represent the island that you love in what seems the most authentic way and that includes its Caribbeanness?

LCK: Puerto Rico is Caribbean, geographically, geologically, historically, culturally, environmentally, linguistically, musically, dietarily, and even politically. Puerto Rico is located exactly at the crossroads where the Greater Antilles meets the Lesser Antilles, just a couple of islands over from Jamaica. Nonetheless, sometimes writers from the English-speaking Caribbean who have visited Puerto Rico have been surprised by its Caribbeanness, in all senses. I guess that is because the Free Associated State of Puerto Rico is still a territory of the US maybe they were expecting just to see US strip malls everywhere, not mountains that look so like the Blue Mountains of JA, dishes and dance rhythms that are familiar, and people of complex Creole ancestry with family structures and lifestyles that clearly express a form of Caribbeanness. The Caribbean literary tradition is not just the anglophone tradition.

I am interested in the connections between the Spanish-speaking and English-speaking islands - all of the islands (and their diasporas) in all of their linguistic variations. A poet here in Puerto Rico has told me that one of my literary contributions is trying to make the link between Puerto Rico and the other islands. Several Puerto Rican poets actively participate in literary events in the other islands and South America, though, more than I do. Some publish bilingual books. The difference might be in how writers collaborate with writing communities across language boundaries and where their primary reciprocal literary friendships are formed. I also teach literature of the English-speaking Caribbean at the university here.

I write out of the tension of my own identity complexities as an immigrant belonging for decades to the Caribbean and being situated in multiple spheres of the Caribbean. I just represent my own observations, inspirations, concerns, and criticisms as one writer - in touch with long-standing literary traditions. In my writing, I do deliberately place Puerto Rico in the Caribbean in relation to both its own literary and musical traditions and anglophone Caribbean poetry and fiction.

AML: Was there a big picture or vision or where you wanted to go in its organisation before you started putting the poems together for a book?

LCK: I had an idea or two to frame the collection when I began writing it related to writing about parts of Puerto Rico outside of the San Juan metropolitan area and focusing on some of the forms of colony we maintain inside this colony. The third section of Ricantations does have several poems that stem from my original ideas, but the book became a playful, living beast as I wrote it, and other themes and aesthetic approaches to the poem emerged. Marvellous elements crept in.

The finished manuscript was relatively easy to organise into four titled sections and order poems. The monstrous, mythical, and shadowy figures in the first section, "Come, Shadow," trace how this society relates to the poor, the dead and dying, the physically anomalous and misshapen, the psychologically ill, the debilitated, and the outcast, human or animal. But the section also contemplates cultural resurrection as symbolised by the cover. "Revel Rebel," the second section, is an assortment of people poems, persona poems. "Memoir of Repairs to the Colony" is about history and rural parts of the island, small sister islands, and the people who somehow give something significant to their communities. It ends with the title poem, which is about Hurricane MarÌa and its aftermath.

The final section, "Art Brut", includes ekphrastic poetry (poems about art), two poems (one about the cover artist for my book, Samuel Lind), and two long-poem sequences, one, in part, about a Puerto Rican man who built his home in the form of a sleek space ship, and one about a glass mosaic artist who crafts virgins dressed in Caribbean flora, nearly all of them "arsenic-eating white," not the sole colour palette for Caribbean women. I see the big picture now - how the poems relate to each other.

AML: Do you think that this book differs in its approach to description or narrative compared to your previous book? Do you see obvious differences when you read both books? Do you think a poet's books should be different in terms of style? Should we always see a progression or change? When you read a poet's work, do you look for changes/differences in the collections?

LCK: I think that each poem calls for its own form, style, and voice. I do see differences between my two collections. In both, I have a quiet sense of humour at times, a desire for the precise word, and a commitment to Caribbean society. In the first collection, poems were set in several islands, including, but not exclusive to, Puerto Rico. In Ricantations, poems are set in London, England, California, Mexico, Trinidad, and Vieques, but more focus is on Puerto Rico. The first book contained spiritual and magical elements, but this book does more so and invokes myth, the monstrous, and a cast of creatures. Both books deal with violence, and specifically, historical, drug-related, or gender violence. Both refer to art and music. Both are feminist, but this one pays tribute to several men who pursue their passions and obsessions without, ostensibly, causing harm. Caribbean masculinity, both positive and detrimental, is a topic. Although the first book experimented with some poem sequences and the long poem at times, this one includes more experiments with the long poem.

I don't have prescriptive ideas about how poets should change up their style from one book to another, but I admire some poets who have done that so well. Vahni Capildeo comes to mind. Her collections are all quite different from each other as a comparison of three of her recent books, Utter, Measures of Expatriation, and Venus as a Bear, demonstrate. Ann-Margaret, your collections The Festival of Wild Orchid and Kingston Buttercup show a progression, expanding themes in the second, travelling from Jamaica to China and Venezuela in search of family history, and engaging with the disturbing narratives of Thomas Thistlewood's diary In Miserable Slavery.

AML: How long did the haunting 'Come, Shadow' take to write? Do poems this close to home take a longer time than others to feel complete because of how emotionally close to the bone they are, or is it that if you are in the "poet zone," the complete poem comes quickly no matter the subject?

Excerpt from 'Come, Shadow':

This day is in 1966, and the present year, the 50th

since my mother was strapped to the laboratory table,

electrodes placed at her temples and chest, a gag -

a plastic bit in her mouth to prevent tongue swallowing

and teeth breakage.

I see the dials on the machine

that someone will have to set for intensity,

the levers that someone will have to turn on

for a duration until she reaches the crescendo,

her whole body a stiff divining rod,

that then jerks in mal seizures, until, in fact,

she leaves her body and billows above it,

a blue-grey shadow of a sail, like the Holy Ghost.

LCK: Come, Shadow is a poem about my mother, now deceased for more than a decade, who was diagnosed as a "paranoid schizophrenic" and had been hospitalised for extended periods in large state-run psychiatric hospitals on three occasions by the time that I was five years old. The poem remembers one visit that my father and I made while she was hospitalised for my entire year of kindergarten, as well as stories that she told me over the years about her hallucinations and the forced therapies, including hydro-therapy and electroconvulsive shock treatment.

This poem came to me at the end of writing Ricantations. One day, I was able to remember the name of the state hospital and the physician who had given my mother the shock treatment. When I felt that I wanted to write a poem about her, I looked at old Internet photos of that hospital and other psychiatric wards from the 1960s, over 1,000 photos in a couple of days, probably. They were so haunting, and they perfectly evoked the stories she had told me. When I sat down to write the poem, it came in a flash, in one sitting, as if I had been waiting to write it for fifty years.

Next week, we continue with the revealing interview with Loretta Collins Klobah as we explore the writer as chronicler, painter of portraits of persons we probably would never meet in history books, but persons who constitute an island's fabric. We will also see how Collins Klobah uses poetry as a mirror, reflecting social issues that in the Caribbean context are often fractious and sensitive.

- Ann-Margaret Lim is a poet and lover of the arts. Her books, The Festival Of Wild Orchid (2013 Bocas Prize Honorary Mention) and Kingston Buttercup (2017 Bocas Prize Poetry Short List), are available at Bookophilia, Hope Road; Bookland, New Kingston, and other supermarkets and pharmacies islandwide. Contact her at annyinpin@hotmail.com