Trevor Munroe | Advancing in the justice system; lagging in control of corruption

Vision 2030, Jamaica’s National Development Plan, was initiated, prepared and finalised in 2009, with input from the Bruce Golding administration, the Portia Simpson Miller-led Opposition, government ministries, departments and agencies, as well as several stakeholders, including students, academics, professional and business organisations, trade unions, non-governmental organisations and the man in the street.

This widespread consultation crafted the national vision – to make “Jamaica the place of choice to live, work, raise families and do business” by 2030.

Today, in 2019, at midpoint between 2009 and 2030, the Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ) tells us that we are on schedule with one quarter of the indicators but behind on three quarters.

As most of us know, in relation to the economy, we are pretty much on target and, in some cases, ahead of schedule, for example, in reducing the annual rate of inflation, increasing earnings from tourism and reducing levels of unemployment.

In that last regard, however, we would be well advised to be cautious, as the data is not readily available on average earnings in each sector, on the extent of “decent jobs” providing for secure employment (as distinct from contract labour), including pension benefits, as well as vacation, sick and maternity leave, etc.

Equally difficult to come by is up-to-date data to confirm or refute the appearance of widening gaps between the top five per cent and the rest of the society.

It was Minister Audley Shaw, in the special sitting of Parliament, which I attended, to honour the late Prime Minister Edward Seaga, who reminded us that in 1967, Jamaica’s annual economic growth was at an all-time record high. He did not mention, however, and all of us would do well to recall, that this economic growth was largely among ‘the haves’, excluding ‘the have-nots’, and was taking place on the eve of social unrest, precipitated by the 1968 Rodney riots and reflecting a widespread popular discontent with high levels of equity in the society.

Nevertheless, the current economic performance has to be welcomed, even as it needs to reach down more to the man in the street.

MILESTONE ACHIEVEMENT

Not so well publicised and less appreciated is a milestone achievement in Jamaica’s justice system. The Gleaner headline on Monday, June 17 read ‘Case clearance rate tops 103 per cent in parish courts during first quarter’. This means that for every 100 new cases filed in the parish courts, approximately 103 were disposed of or completed.

This exceeded the international benchmark, was the highest recorded since the establishment of the statistical unit in 2016, and was well above the target set for 2018-19 in the national development plan.

Extraordinary clearance rates were achieved in the parish courts of St Mary (162-plus per cent), Portland (137-plus per cent) and St Catherine (129-plus per cent).

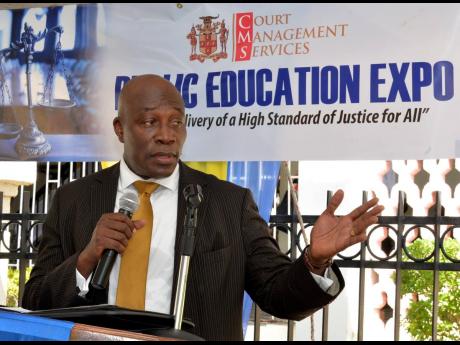

Given the importance of the high clearance rate as one factor in reducing the long waiting time Jamaicans have long endured for cases to be disposed of in the parish courts, I fully agree with Chief Justice Bryan Sykes’ comment, “while there is still a far way to go ... Jamaicans should be encouraged and hopeful that our judiciary is on course to become the best in the Caribbean in three years and one of the best in the world in six years as it relates to the delivery of legal services”.

Meeting the national plan’s goal of a secure, safe and just society requires that the judicial branch, co-equal to the executive and the legislative branches, sustain this first-class performance.

Commendations are due to all concerned – the former chief justice, Zaila McCalla, during whose administration a statistical unit was set up to measure performance; to the court staff working diligently with the statistical unit; to the senior parish court judges, who are in charge of the parish courts; and ultimately to Chief Justice Sykes himself, whose leadership has built on the foundation of his predecessors.

In particular, the chief justice has been adding a new dimension to the traditional training programmes in ‘continuing legal education’ – that is, two- to three-day seminars now incorporating specific training for parish court judges and court staff in the disciplines of leadership.

It was in July 2018, in association with the National Integrity Action and the Judicial Educational Institute, that the internationally renowned Franklyn Covey Organisation was first commissioned to guide interactive sessions in leadership at the Norman Manley Law School, initially for two batches of parish court judges. This training is contributing to the empowerment of our parish court judges by imparting the intellectual tools to move from the idea of improving our courts to the practical execution of that mandate, once again demonstrating that relevant training and quality leadership are critical to the success of any transformational process.

URGENTLY APPLIED

These lessons need to be urgently applied in relation to other areas where effective governance is lagging. For example, in relation to the rule of law and control of corruption, our performance, according to the National Outcome Indicators published by the PIOJ, falls well below the target we set ourselves for 2018-2019 and contributes to increasing lack of confidence among our people in Jamaica’s democratic institutions.

Similarly, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) also warns us in its May 2019 Fifth Review on Jamaica’s Stand-By Agreement that “weak governance and corruption can severely hamper economic growth … and the rule of law”. The IMF also reminded us that “Jamaica also underperforms relative to its peers on a variety of corruption co-related fiscal measures” and that the “functionality is yet to be tested …” of the Integrity Commission “to address corruption risks among parliamentarians and public officials”.

In that regard, I urge the commission to pass the test, apply the law, without fear or favour, and follow precedents in recommending action against parliamentarians whose statutory declarations remain incomplete.

Beyond this, with so much “unexplained wealth” obvious to the naked eye in Jamaica, the Financial Investigations Division, the Major Organised Crime and Anti-Corruption Agency, the Revenue Protection Division and the Office of Director of Public Prosecutions, as well as other investigative and prosecutorial authorities, need to pay increased attention to the incidence of ‘illicit enrichment’, that is, the offence whereby public officials have assets and income beyond their known legal sources.

It is encouraging that in one year, 2017, 1,844 cases of corruption, with 519 convictions, were secured in the parish courts, but deeply disturbing that in the seven years for which I have secured data, there have been a grand total of seven convictions of bigger fish for illicit enrichment.

I urge the public officials of integrity in our criminal justice system to summon up the courage to apply the directive in our National Security Policy, as is now being done with the corruption case involving the Manchester Parish Council – “the focus has to shift from street level criminals to the top bosses who enjoy and control the profits … the facilitators … the politicians, lawyers, accountants, doctors, businessmen, real estate brokers, who operate in both the licit and illicit worlds … targeting the top bosses ... is ... the most effective way to degrade criminal networks, seize their assets and undermine their power” (Page 29-30).

Professor Trevor Munroe, CD, DPhil (Oxon), is the executive director of the National Integrity Action (NIA). Email feedback to tmunroe@niajamaica.org and columns@gleanerjm.com