Alfred Dawes | Not my Haitian

The driver of the grey Mitsubishi Pajero who crushed the skull of Demar Lilly while stealing a bottle of his honey is still at large at the time of writing. But the silence is deafening so we shall move on.

Dr Alfred Xuma was the first black South African to become a medical doctor. An activist against racial discrimination in his homeland, he became president of the African National Congress (ANC). He is credited in revitalising the ANC – regularising membership and improving the finances of the organisation. He was a very distinguished man in South Africa and was accepted by many whites who were supporters of apartheid. In fact, he was so entrenched in white society that he found it difficult to entertain the radical youth in the organisation which he led.

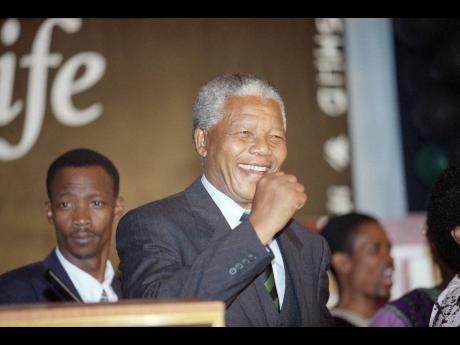

One such radical, a Mr Nelson Mandela, believed that Xuma enjoyed the relationships he had formed with the white establishment to the point where he did not want to jeopardise them with any political actions beyond letters, and delegations to lobby the ruling elite. One cannot discount the role that Dr Xuma played in the liberation struggle in South Africa. But there is a reason we recognise the name of the hothead as perhaps the greatest civil rights activist since Gandhi, and not Xuma. And that reason transcends time and geography.

THE ESTABLISHMENT

Five years ago, when I became an agitator for improvements in healthcare, I met with one of my mentors and we chatted about my work with the union. He gave me a history lesson on the mavericks of previous generations and their evolution with time. He ended with the statement. “You are a radical now, but one day you will be a part of the establishment.”

I wondered at the time if it was a subtle admonishment to be more mindful of who I was criticising, as they had played their own roles in national development. But with time, I understood that he was giving me a timely reminder that even when one has formed relationships with the establishment, they should remember the outrage at injustices they felt before it was tamed by gentrification.

As we progress in life and society, we will form bonds with the very people who deserve our criticisms and sometimes vitriol. But they are now a part of our clique, we have business relationships with them, and social gatherings may suddenly become awkward because of the presence of mutual friends. It becomes harder and harder for us to call it as it is. In fact, it is easier to circle the wagons and protect our own from the mob. We become Dr Xuma.

Yet at the same time, we turn up our collective noses at those ghetto people who are blocking roads to protest the killing of an unarmed youth by the authorities. It is clear he was no altar boy, we say. There they go defending criminals again. That is why we will always have a crime problem because they defend the murderers.

HYPOCRITICAL

Isn’t it hypocritical then that we choose to give white-collar criminals the benefit of the doubt, preferring to reserve judgement until they have their day in court? The reality is that even if by all appearances they are guilty, chances are that they will get off on technicalities because they can afford high-level legal representation compared to overburdened legal aid volunteers reserved for ghetto denizens.

We are programmed as individuals to be empathic to those who are in our circle and to be loyal to those who have lent us a helping hand. It doesn’t matter if it is the corrupt official or the community don who helps with back to school. The biggest problem with tackling corruption in our society is that those who are in the circle of the corrupt are the ones with the power to effect change but refuse to do so because of the reasons outlined.

The power brokers, being humans, will not lend readily to the anti-corruption campaign but still find corruption abhorrent and something to be fixed urgently.

But what if the movement continues without them? Can rooting out corrupt individuals be precisely achieved with mass action?

When the coalition forces toppled Saddam Hussein in the last Gulf War, they embarked on a programme of ‘de-Ba’athification’ – removing members of Hussein’s Ba’ath party from positions of influence in the government. The goal was to rid the country of the men who supported the dictator and usher in a new era of democracy and stability. It was a disaster.

The overzealous pursuit of party members led to many, guilty by association or tribal origin, being stripped of their livelihoods and left with no options but to join the insurgency. People who had joined the party not for the support of its leader or philosophy, but as a means to help their careers, were labelled as one of the corrupt oppressors.

This contrasted with the approach of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa that allowed members of the old apartheid regime to continue with their lives after facing their victims and accusers.

SMELL OF BLOOD

When the mob smells blood, the rationality of the individual becomes superseded by the raw, passion-filled desire for justice and revenge. Innocence and guilt become mere illusions in the trials of the fallen. Lesser offenders and those guilty by association are lumped with the masterminds and henchmen, and that can result in the undeserved tarnishing of good men who only wanted to serve. They become casualties in the war being waged.

As we tackle corruption, we have to be wary of the natural biases we have to protect those who are from the cohort of the corrupt, but who are close to us. Otherwise we will be a part of the problem, enablers of corruption.

I once had a conversation with a Bahamian who spoke of the colonisation of his country by illegal Haitian immigrants.

“They are coming in droves, taking our jobs, responsible for the majority of the crime and they outbreed our Bahamians three to one. In a couple of decades, by sheer numbers alone, they will take over our country if we don’t get rid of them all,” he said.

His conviction was resolute. Haitians had to go to save his people.

“But what about your gardener, he’s Haitian?” I queried.

“Oh no, not my Haitian. He’s a good one,” he responded.

n Dr Alfred Dawes is a general, laparoscopic and weight loss surgeon, and medical director of Windsor Wellness Centre & Carivia Medical Ltd; Fellow of the American College of Surgeons; former senior medical officer of the Savanna-la-Mar Public General Hospital; former president of the Jamaica Medical Doctors Association. @dr_aldawes. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com and adawes@ilapmedical.com