Editorial | CARICOM must put COVID-19 house in order

Jamaica’s move for a coordinated Caribbean response to Britain’s discriminatory approach in deciding which countries’ citizens are properly vaccinated against COVID-19 to enter the United Kingdom (UK), continues to be endorsed by this newspaper. In fact, as we proposed last week, the Caribbean Community’s (CARICOM) effort should be broadened to a campaign for a fair, transparent and predictable system for vaccination recognition and international travel.

But equity also requires that CARICOM puts its own house in order. The region cannot demand fairness from others, if, among itself, it engages in behaviour similar to what Britain has been accused of. For instance, a citizen of Trinidad and Tobago, or someone who was in that country up to 14 days prior to arriving here is ineligible to travel to Jamaica, even if that person is fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

That travel restriction was put in place months ago when Trinidad and Tobago was battling a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases, driven by the Delta variant, and the country’s vaccination rate was significantly lower than at present. Up till September 24, an estimated 41 per cent of Trinidadians had received at least one shot of a vaccine, while 34 per cent were fully vaccinated. In the case of Jamaica, 18 per cent are partially vaccinated, but over 7.5 per cent was fully inoculated.

TRAVEL APARTHEID

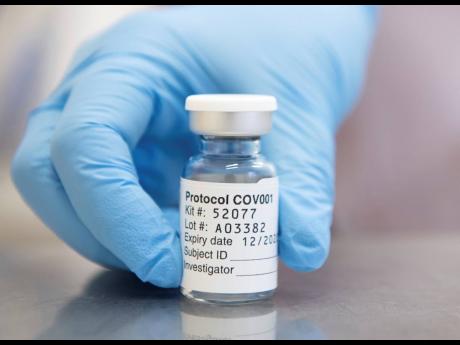

The prospect for a sort of travel apartheid, with one set of rules for some countries, rich ones, and another for poor nations, became sharply apparent to Jamaicans recently. They discovered that despite being fully vaccinated at home (even with a vaccine developed by two venerable British institutions, the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca and Oxford University, and donated to Jamaica by the British government), when they travelled to the UK, they have to jump hoops that are avoided by vaccinated travellers from many other countries. The UK does not recognise Jamaica’s vaccination regime, although what the Brits find at fault with Jamaica’s system is not clear – the skills of the healthcare professionals who deliver jabs; questions about how the information is recorded; or may have concerns over the quality of the paper used for the vaccination certificates.

In the face of public outrage against Britain’s stance, Prime Minister Andrew Holness felt driven to defend the integrity of Jamaica’s system, insisting that not only was it of the highest standard, but that all information on the vaccination certificates could be verified.

“We track everyone who has taken the vaccine,” Mr Holness said. “So, if you needed to travel, and you arrived in the foreign country and presented your card, there will be the appropriate systems to ensure that the country you have travelled to can verify your card on the Jamaican database and be satisfied that your vaccination is legitimate.”

RAISED HACKLES OF INDIA

It is not only Jamaica that has spoken out against Britain’s discriminatory treatment of some vaccinated people. The matter has also raised the hackles of India, causing a minor diplomatic spat between London and New Delhi. The Indian government is particularly peeved that while Indians, even if fully vaccinated, are, like Jamaicans, subject to extended isolation and additional COVID-19 tests. The vaccine mostly used in India’s vaccination programme is the same one developed by AstraZeneca. The only difference is that it is manufactured in India. In fact, millions of doses of the Indian-manufactured vaccine have been exported to the UK and presumably administered to Britons.

Although the UK plans to simplify its travel system, by reducing the band of countries subject to varying restrictions, from three to two – countries whose vaccinated citizens have relatively easy passage into Britain and the others – that ensures neither transparency nor fairness in the system. The latter list will likely still include countries whose vaccination regimes will not receive the UK’s seal of approval. Further, only a limited group of vaccines will be recognised.

With the United States planning from November to allow only vaccinated people to enter the US (the rules for which are still being developed), there is obviously the need for a predictable, rule-based system for global travel. The World Health Organization (WHO) might establish a model regime for COVID-19 vaccination reporting, whose implementation by states could be invigilated by the WHO. Citizens of countries who meet these standards should, but in exceptional and verifiable circumstances, be afforded the same travel privileges. In that regard, the determination for allowable travel would be whether the individual is vaccinated rather than the a priori blackballing of countries.

Having told the UK that its arrangement sucks, Jamaica and its CARICOM partners will perhaps champion this proposed new regime. But the community has to first make sure that its own house is in order.