Maziki Thame | Landownership and reparatory justice

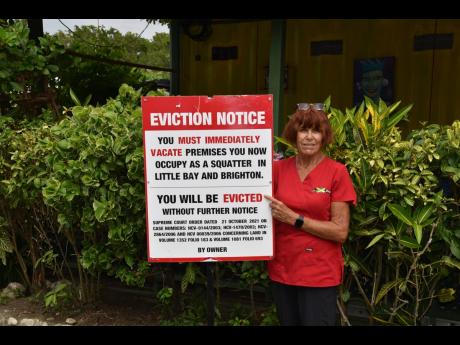

THE PEOPLE of Little Bay, Westmoreland, like the up to 35 per cent of Jamaicans living as so-called squatters, carry the weight of history on their backs. At stake is righting that history. At 60 years of Independence, we should consider this issue as a matter of reparatory justice for the descendants of enslaved Africans in Jamaica.

For the ‘concerned citizen’ who wrote to The Gleaner editor on April 26 in relation to the plight of Little Bay residents, “the phenomenon of squatting is evidence of [the NHT’s] failure to provide adequate housing solutions to the average Jamaican”. It was argued that the practice should not be encouraged. Disappointment was expressed that the opposition leader and the mayor of Savanna-la-Mar, Bertel Moore, would support the “squatters”.

Moore had in 2018 indicated support when tensions were brewing. The Gleaner report of June 7, 2018, ‘Battle for land – MP, mayor side with Westmoreland squatters’, had Moore telling us that the 867 acres of land was bought by a couple with the full knowledge that people (500 settlers) had been living there for 67 years. In 2011, the courts rejected the residents’ claim on the land made eight years prior, and they have been delaying eviction procedures through the courts since. Details of the land sale are surely matters of public interest.

In response to a recent bid by the residents for the prime minister to intervene on their behalf, the prime minister told them that his adminisitration would never allow property rights to be compromised, and since the Government could not afford to buy the land for them, they should think about moving, as demanded by the courts. When the opposition representatives told them to “stand firm” on their claim, Local Government and Rural Development Minister Desmond McKenzie called their advice “disgraceful and dangerous”.

MALDISTRIBUTION OF RESOURCES

Many believe the residents should have no rights to the land because they did not buy it. Many believe property rights should be respected. But we should centre the fact that property rights and the maldistribution of resources in this country emerged from the history that created those conditions in the first place.

When the prime minister proclaims a respect for property rights (as have many public officials before him), we should never lose sight of the fact that the roots of property ownership in Jamaica is land-grabbing. The Europeans who planted their flag and claimed the land had no concern for those people they met on the land. The history created by Europeans bequeathed poverty and landlessness to the descendants of enslaved Africans and property ownership and wealth to Europeans. An uncritical acceptance of property rights is upholding the injustice of history.

To the people of Little Bay (and elsewhere), the prime minister said “disorderly land settlement must never be countenanced,” because that would allow those with political connections, those who know ‘people’ and have ‘badman’ connections who can use force, to get land while the average person cannot. Are so-called average people now able? Which people is it that we should know to get land? Does the use of bulldozers against so-called squatters count as the use of force to get land? Could the people who meet the prime minister’s requirements to own land be those with means to buy 867 acres with people already settled there? Does wealth and connection to the state now, as always, allow for land grabs?

The mainstream narrative against squatting and for the protection of property rights has consistently reinforced the idea that property laws have validity, rather than being rooted in an unjust historical structure of black deprivation. This narrative makes those who claim the land without purchasing it in the present, be seen as disorderly criminals. It often justifies forced removal, beginning with the tragic history of Back-O-Wall in 1963 -- since Independence. What space is there for us to consider these people simply as people who are deprived in the postcolonial, racial power structure? Aren’t they in need of justice?

IMPORTANT FACTOR

Alienation from land has been an important factor in determining the place of blacks from slavery to the present. Black landownership since Emancipation was of necessity attached to squatting, given their lack of capital. Land issues are not merely issues of housing solutions. In our case they are issues of reparations for past injustice, for constructing freedom and creating a just society.

In 1838, formerly enslaved people fled the plantations and settled in the hills and free villages, established by churches to assist them to escape the memory of slavery and to make a way for themselves: to eat and live free from the oppression of the plantations. Many were brought back to the plantations as low-wage workers due to oppressive taxation that added to other economic pressures.

In 1865, Bogle’s efforts at purchasing land for peasants in St Thomas were meant to open the path to self-government. Landownership was needed to be a representative in the legislature at the time. We know the brutal war and killing they faced from the colonial administration in response.

Among the contributors to the 1938 labour rebellion in Jamaica was the rumour that following the 100 years of Emancipation, land was to be transferred from whites to the descendants of enslaved people. It is no small thing that Frome, Westmoreland, (and St Thomas) were where the 1938 labour rebellions began, and it is not unimaginable that the people of Little Bay can trace their roots back to the slave plantations of Westmoreland. It is now 184 years since slavery ended and 60 years since Independence, and very few Jamaicans can ‘afford’ land. Isn’t that a disgrace?

Questions of the relationship between squatting and the paramountcy of property rights must be related to economic justice and reparations for the descendants of enslaved Africans in Jamaica. While some of us recently called for the British royals to pay reparations, we must also settle internal injustices that, at a very basic level, must address the ownership of the resources of Jamaica by the descendants of those who worked the land for free and faced brutal violence, death and dehumanisation in the process.

What do we believe the descendants of enslaved Africans are now due on this land? What is available for those who were impoverished through slavery and have been unable to rise above the waters of history in the 21st century? As we think on the tasks before us at 60 years of Independence, do we believe it is our duty to create a just society premised on the fair distribution of the resources of the land?

Maziki Thame, PhD, is a senior lecturer at the Institute for Gender and Development Studies, UWI, Mona. Send feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com.