Michael Abrahams | An angry child is a hurting child

Last week a high-school student fatally stabbed her female schoolmate on campus. The tragic incident disturbed me but did not surprise me. We live in a violent society, and the cause of much of this violence is pain. So we are a hurting society,...

Last week a high-school student fatally stabbed her female schoolmate on campus. The tragic incident disturbed me but did not surprise me.

We live in a violent society, and the cause of much of this violence is pain. So we are a hurting society, and our children are not spared the agony. When children are hurt, like adults, they may exhibit a variety of trauma responses. Some may withdraw. Others may become ‘people pleasers’ to avoid conflict. And some may exhibit violence. As we see, many do.

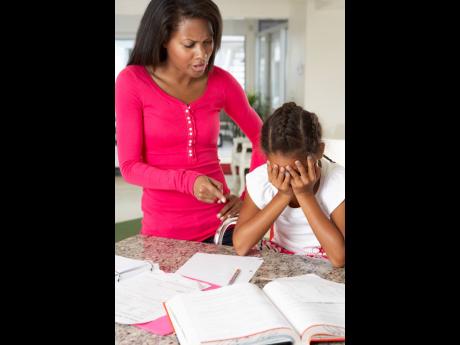

Children are among the most vulnerable among us. Their ability to protect and defend themselves is much less than that of adults, and we do an excellent job of traumatising them. First, we beat them. And we beat them a lot. Multiple studies have found that corporal punishment is not in children’s best interest, and does more harm than good. But partly as a result of the legacy of slavery (slave masters used to beat our African ancestors mercilessly to punish them), we have normalised it and assimilated it into our culture. For many, it is the go-to method of punishment. However, hitting another human being repeatedly is not discipline. It is abuse. And physical abuse is often accompanied by verbal abuse. It is not unusual, while our children are being beaten, for them to be told negative things about themselves, like “Yuh nah amount to nuttn”, or “Yuh wutliss like yuh pupa”.

NEGLECT

We neglect our children a lot. The majority of Jamaicans are raised in single-parent households. Growing up with an absent parent, or absent parents, is not anomalous. Many of our parents have abdicated their roles, leaving the upbringing of their children to others. The expressions, “Mi grow wid mi granny” or “Mi grow wid mi auntie”, are all too common. Some children are fortunate to have loving and nurturing guardians. But in many cases, the family members they are left with are unkind or even cruel to them, treating them differently from their biological children, if they have any, or treating them as servants, or even slaves. This neglect also sets children up for sexual abuse, which is also not uncommon in this country. This violation is often excruciatingly painful and likely to leave deep and permanent scars.

Along with neglect and assaults, our children are exposed to many dysfunctions in the home and their communities. Domestic violence is common in Jamaica. The incidence of mental illnesses, such as depression, has been also noted by researchers to be high in our country. Unfortunately, with the stigmatisation of mental illness in our society, many of the afflicted remain untreated. It is therefore understandable that children growing up in households with adults suffering from these maladies, and not getting help for them, will not be unscathed.

As our children are exposed to so much abuse, neglect and exposure to dysfunction, otherwise known as ACEs (adverse childhood experiences), we ought not to be surprised at the level of anger and violence they exhibit. I recall a boy I attended school with, who had previously been expelled from several other educational institutions, who was always getting into fights. When I encountered him years later as an adult and befriended him, he shared with me the torment he experienced as a child because of his father’s neglect. He said his father was always too busy at work and lodge and board meetings, and the void he experienced from not having his father around was very painful.

REBELLIOUS BEHAVIOUR

I also remember a conversation I had a few years ago with a friend, who related a story of a girl she chose to mentor. The mentorship went smoothly initially, but the child’s behaviour began to change, and she became oppositional and belligerent after a while. My friend became increasingly frustrated, and she terminated the relationship to protect her mental well-being. Years later, when she encountered the girl as a young adult, her past mentee told her that her rebellious behaviour began when she was being sexually molested. My friend had no idea and was crushed by the revelation.

More recently, a patient of mine shared her childhood history with me, a period where she experienced physical, emotional and sexual abuse, neglect, and exposure to violence and dysfunction in the home. “You used to fight a lot in school, didn’t you?” I asked. Her answer was, “Yes.” Not surprisingly, she now has chronic depression and has attempted suicide.

Angry children are often hurting children. The anger, aggression and violence we see are manifestations of their pain. They act out, rebel, fight and bully other children. If we want to see less violence among them, we must stop hurting them. But to do that, we must first fix ourselves. Conversations about mental health must be encouraged, and mental illness and therapy destigmatised. More discussions and forums are needed to educate not only parents, but also prospective parents about parenting. And we need the populace to understand that corporal punishment is not necessary to discipline children. These measures will go a long way towards breaking our cycle of abuse and pain.

Michael Abrahams is an obstetrician and gynaecologist, social commentator and human-rights advocate. Send feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com and michabe_1999@hotmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @mikeyabrahams.