Editorial | Constitution reform priorities

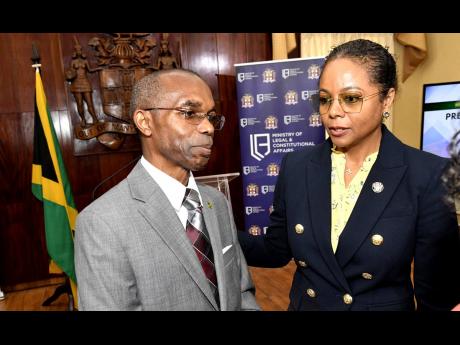

Marlene Malahoo Forte and Rocky Meade, the joint leaders of the lawyer-laden committee that is to make suggestions for updating Jamaica’s Constitution, have three urgent tasks.

First, they have to convince sceptical Jamaicans that they are not a stealth duo intent on eroding existing rights and freedoms, on the grounds that it is necessary to combat crime.

Second, and related to the first point, they have to establish a work format that makes it easier for all Jamaicans, including ordinary folk, to contribute to their deliberations.

Finally, which is related to the second point, there is no need to reinvent the wheel, even if there is need for upgrades. Much good work has already been done by previous constitution commissions, including the one that sat in the mid-1990s. Many of whose recommendations were embraced in a 1995 report by a joint select committee of Parliament.

That report should be republished and widely circulated not only as the starting point for the committee’s deliberations, but as an opening to its engagement of citizens. It would be useful if people were reminded what was previously on the table and around which there was consensus.

MORE AMBITIOUS

It is an opportunity, too, for the Government to be more ambitious – beyond transforming Jamaica from monarchy to republic – during what Ms Malahoo Forte, the legal and constitutional affairs minister, sees as the first phase of the reform process.

While committees of this kind are, by definition, interrogative and curious, willing to follow all strands of opinion, they are expected to be informed by the expertise that resides within them. Their outcomes, too, are often influenced by, if not reflective of, the thinking of their leaders.

In that respect, neither Ms Malahoo Forte nor Lieutenant General Meade will be surprised, or offended, that some people harbour questions about the philosophy they will bring to their roles.

Lieutenant General Meade was recently named a special ambassador, to operate as a sort of public sector troubleshooter, fixing things that are not being done properly, which Prime Minister Andrew Holness deems as priorities for his Government. Obviously, constitutional reform, or elements thereof, is one of those.

Prior to this assignment, Lieutenant General Meade was chief of defence staff of the Jamaica Defence Force and a major proponent of the use of states of emergency to combat the island’s problem of violent crime. In mid-2021, he criticised Jamaicans who were unwilling to trade guaranteed rights for the sake of security.

“We do not have an appetite to forgo, temporarily, some of our rights in order to secure the right to life,” he said. “... We don’t seem to understand that the right to life should supersede all other rights.”

How this view may seep into, or impact, any discussion on reform of Jamaica’s Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms will be closely watched.

Indeed, on this issue, the co-chairs of the Constitutional Reform Committee have similar views. In 2016, Ms Malahoo Forte, then the attorney general, warned that “fundamental rights and freedoms guaranteed to Jamaicans may have to be abrogated, abridged or infringed” in fighting criminality.

Of course, such opinions do not totally define either person. Critics, for instance, are likely to be reminded of Lieutenant General Meade’s key role in the establishment of the military-grounded Jamaica National Service Corps that has delivered skills to hundreds of young people.

PRIVILEGE OF THE CHAIR

Moreover, while Ms Malahoo Forte and Lieutenant General Meade have the privilege of the chair, they are surrounded by intelligent, skilled and experienced committee colleagues, who will insist on all viewpoints being heard. These guardrails can, however, be strengthened by an open and transparent process which robustly encourages citizens’ participation.

Although the first listed committee’s mandate is to assess the 1995 reform proposals against the backdrop of today’s realities, the Government has made its priority ditching the British monarch as Jamaica’s head of state and replacing the king with a non-executive president.

This newspaper supports the repatriation of this critical symbol of Jamaica’s sovereignty. But of equal symbolic importance, and of greater practical value, would be ending the practice of seeking justice from the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, Jamaica’s highest court, via a prayer to His Majesty.

Indeed, there was consensus in the 1995 commission, as well as the parliamentary committee that reviewed its finding, that appeals to the Privy Council should end “if and when” a Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) was introduced.

The CCJ has been operational for 18 years and the high quality of its jurisprudence is in no doubt. Neither is the fact that accession to the court would widen access to the top tier of justice for the majority of Jamaicans.

Accession to the CCJ is constitutionally far easier than transitioning to republicanism. Jamaica, nonetheless, straightjacketed itself out of the court not out of some philosophical concern, but because of political denialism, the reason for which few remember or genuinely believe in. We should free ourselves of that enervating approach to politics and policy – and of the Privy Council.

In the first round of reform, the Electoral Commission of Jamaica, the Office of the Public Defender and the Integrity Commission should also be entrenched in the Constitution.