Family reflect on Bunny Wailer – the Blackheart Man and Don Dadda - Documentary gives insightful slice of history

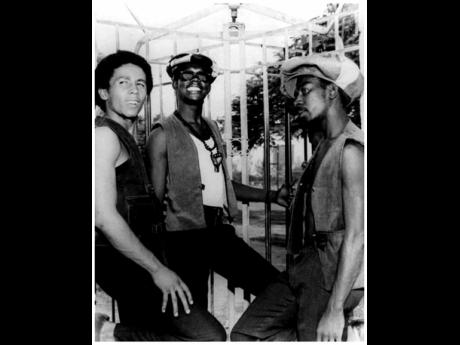

Carl Livingstone, the older brother of Bunny Wailer; Danny Livingston, his younger brother; Cedella Marley Booker; Asadenaki Livingston, Bunny Wailer’s son; and Maxine Stowe are some of the persons who feature in Blackheart Man, a mini-documentary tribute to Neville O’Riley ‘Bunny Wailer’ Livingston.

Like the legendary Wailer himself, the project is multilayered and seeks to make simple the complex. The 30-minute documentary, released in celebration of the 73rd birthday of the three-time Grammy winner, explores familial relationships, his journey with Rastafari, his own music, and the catalogue created as part of the legendary Wailers, alongside Bob Marley and Peter Tosh. Bunny Wailer is on a mission to ensure that The Wailers as a group is not airbrushed out of history.

There are numerous stories floating about, fingering the person(s) who “mash up The Wailers”. However, the narrator in the documentary, while repeating what is already known, that after the Catch a Fire tour (April-July 1973), Bunny Wailer stopped touring owing to his Rastafari faith, also states: “The Wailers never broke up. Bob, Peter, Carl, and Aston performed on Bunny’s solo project and decided to support each other as solo artistes.”

“He really misses his brothers. We will never understand the relationship they had growing up as a family, suffering together, rising together,” is Asadenaki’s take on his father’s reaction to the deaths of Marley and Tosh. And brothers they were. Bunny and Bob’s story started in Nine Miles in St Ann. “I was about seven, Robert (Bob Marley) was about nine. We went to the Stepney Elementary School,” Bunny Wailer explains. There was “something special between Taddy (Bunny’s father) and Cedella (Bob’s mother), and both moved to Trench Town from Nine Miles”. That ‘special’ relationship produced a daughter named Pearl. Interestingly, Peter later fell in love with one of Bunny’s other sisters and their son, Andrew Tosh, is now carrying on his father’s legacy.

Asadenaki relates a dream his father had about how he and Peter were at the National Stadium and saw the cops carrying a man outside. The man was distraught because he said he had seen Bob Marley inside, but Marley, at that time, was dead. When Bunny and Peter went inside, they saw the man, who closely resembled Bob. “So Peter go up to him and there was a name that Bob alone used to call Peter – Perks. The man looked at Peter and said, ‘A wha happen to you, Perks?’ And Peter just jump pon him and hug him and hug him. Jah B seh when him wake up from that dream, his pillow wet with tears,” Asadenaki recounts in the documentary.

Experienced music-industry player Maxine Stowe hails Wailer for so precisely living his faith. “His spirit led him to stop touring on the brink of international stardom and to owning his own catalogue. That’s the spirit of the B lackheart Man (the title of his first solo album),” she said. Not only did Bunny Wailer set a precedent by owning his catalogue, the group blazed a trail with the establishment, in 1966, of the first local, artiste-owned record label, Wailing Soul, and later, the Tuff Gong label.

Jailed for ganja

The story of Bunny Wailer is closely interwoven with the herb, and in the ‘60s, he was jailed for ganja. He remembers it like this: “In those days, police raided Trench Town quite often. That day I was there, but Tata – a bredren who we all loved and respect (Robert Marley wrote songs and put them in Tata’s name) – was in hospital,, and the brothers were there doing things for Tata. While there, the police raided because one of the brothers took the herb from where Tata had it and took it on the street and was selling. I was there and the police held on to me too.”

Years later, Bunny Wailer found out that his case had been dismissed, but he had served the 14-month sentence in the Richmond Farm Prison anyway. While there, he wrote the song B attering Down Sentence.

Asadenaki, who recently shared his thoughts with The Sunday Gleaner, stated: “I feel it’s a magnificent reality that he is still here to tell his story. His experiences are historic milestones of our growth as a culture and as a people. It is out of this love that The Blackheart Man documentary was spawned.” He hailed narrator Simone ‘Chuka’ Simpson for her production role in the project and Jack Sowah, popular dancehall cameraman, who was very instrumental in the archival process.

Bunny Wailer’s catalogue runs across the spectrum of roots reggae, dancehall, electronic, and rap. He originally wrote and recorded Marcia Griffiths’ Electric Boogie, which reached number 51 on the US Billboard Hot 100 in 1990. In the documentary, Bunny Wailer is seen dancing up a storm to the Electric Boogie.

“He’s like the Don Dadda he speaks of,” Stowe says as she likens him to a fire spirit. “I have met a lot of people culturally who have a hot spirit, so I understood the fire spirit. It is a hard shell to a soft person. And it has served him well.”

In the background, Bunny wails, “Jah love, it is like a burning fire. It keeps on burning, burning, burning. In my soul.”