Bernard Headley | I could have been among Prime Minister Theresa May’s disinherited (Pt 2)

The Great Migration to Great Britain of the Jamaican peasantry began in 1948 when 482 men paid their £28 fare and boarded the Empire Windrush vessel bound for London. In the next 10 to 15 years, hundreds of thousands of Jamaican men, their wives and children, would make the journey.

For Britain, whose industrial infrastructure had suffered ruinously from relentless bombardment from German Luftwaffes, the Great West Indian Migration meant reclaiming an international foothold. The country needed a mass of strong, able-bodied men who could work hard and long

The benefit seen by the massive numbers of people from below was that migration to Britain was an opportunity to escape persistent poverty.

The older groups of men were less sanguine. They anxiously talked about wives and children they were leaving behind. Some said they were only going up for maybe five to 10 years and send back some funds. A larger number of the more mature men indicated that they planned to send for their wives and children in a year or two; that they would be planning to bring them up to Britain and resettle there. This, they figured, would give their children a leg-up on the chance for a good education and, ultimately, a rewarding profession.

My father's thinking in 1952 was clearly in the latter camp. He had viewed his situation as dire, if not desperate. He needed a plan to join his rural compatriots in migrating to England. But he knew that this could not be a topic he could raise with our mother, who had, over the years, forcefully resisted any such talk. He figured, however, that he simply had to "take the bull by the horns". He had to strategise a plan that was stealthy but not devious. And the plan would have to be so well laid that by the time his wife could try to coax him out of it, he'd be well out in the Atlantic. Once in Britain, he'd save enough to send for his family. Their one-way, no-return tickets would be their escape from a life of endless hardship and uncertain future.

First things first, though: Uncle Windsor had told him that he needed to see about his passport and to obtain a reference letter. Having recently travelled to a couple of Caribbean islands (selling books as an itinerant, persevering Adventist colporteur), he had a passport, a British passport, which meant that as a colonial British subject, he could live anywhere in Britain, the 'mother country', as a British citizen. The same would be true for his dependent children, who would be travelling up on their mother's anticipated British passport. He'd have to see about the reference letter.

Journey to Nowhere

One of the things my father gave up when he joined his wife's Mount Carey Seventh-day Adventist Church was his nice, cushy job as the driver of a McCauley's Royal Mail vehicle. He loved that job. The Royal Mail route plied between Anchovy and Green Island, Hanover.

He resigned because it involved working on Saturdays, the Adventist Sabbath.

My father left McCauley's bus company with new-found respect from his boss. Any man who held so firmly to his religious beliefs and religious values, Gerald McCauley had told him, was a principled, solid, and morally sound man. If there was anything he could do for him in the future, McCauley told my father, he'd be happy to do so. He further said that he'd be always looking out for him.

Seven years of fits and starts, disappointments and harsh failures, after marrying and leaving his steady job, led my father to his secret going-to-England plan. For that reference letter, he would secretly go to his friend and former boss, Mr McCauley.

When my father, on a Tuesday morning in April 1952, walked into McCauley's office in Kingston, the wealthy, brown-skinned Jamaican company owner greeted him with exuberance, excessive mirth, slapping him several times on the shoulder. Clearly, McCauley had something to tell him, but he let my father talk first. My father explained to McCauley the reason he had come all the way from Mount Carey to see him. At that point, McCauley burst out in laughter. "You are not going to no England, Headley. Fahget it," he said, whimsically, yet assuredly.

"Just yesterday, I was calling your name. I was searching how to get in touch with you, and here you are!" McCauley told my father. "You know why? Last week I signed a hell'va contract with the Canadian bauxite company that recently started operations in Williamsfield, Manchester." (The plant would later be named Kirkvine Works.)

The contract McCauley signed with Alumina Jamaica Limited was for his company to allocate four 32-passenger-seat buses, with drivers, to transport from Mandeville to the plant, and back to Mandeville, expatriate and white-collar workers. "But you know why I've been thinking of you, Headley? I need someone to put in Mandeville to both drive a bus and supervise the entire operation. The most qualified, principled and honourable person I could think of for the job was you. And you know what the most beautiful thing about this job is, Headley, which you will love? It won't involve no Saturday work! You park the buses on Friday evening and you can go and worship your God in peace all day Saturday."

McCauley did not ask whether he accepted or not. He simply said, "I need you in Mandeville first thing next week to assume responsibilities." My father said he'd be there.

No argument

My father returned to Mount Carey with the exciting news but only telling my mother the part about the new job, not about his original intent in going to see McCauley. Would she consider pulling up her Emancipation-era roots in Mount Carey and move the family to live in Mandeville? The children could attend the Adventist school up there. Right?

She said yes.

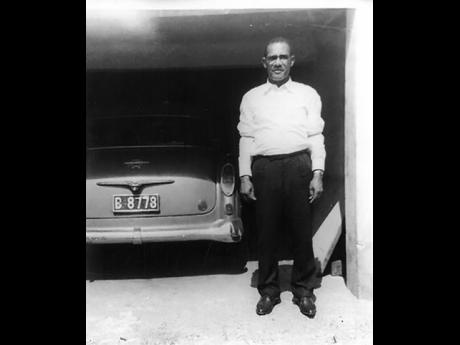

Together, my parents built in Mandeville a modest but comfortable house. And my father, for the first time in his life, was able to purchase a presentable car - a 1959 Opel sedan, a German car! Around the family dinner table one Sunday, several years after the move to Mandeville, he confessed the details and full scope of his going-to-England plan. My mother sat in cold silence listening. After he was through telling his story, she falteringly rose from the table, stood up and testified in words that echoed the language of the hymn writer Eliza E. Hewitt: "I need no other argument."

Spared, we certainly were, from Tory government-heaped ignominy of no re-entry, removal and deportation.

Kamal Headley assisted in the production of this column.

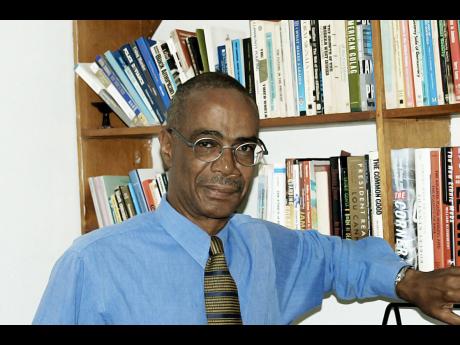

- Bernard Headley, PhD, is a retired professor of criminology, UWI, and professor emeritus of sociology and justice studies at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago, Illinois, USA. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com and bernardheadley1@gmail.com,