Delano Franklyn | Racism, United States and ex-cricketers

The recent storming and occupation of the centre of government in the United States by supporters of President Donald Trump has, once again, brought into very sharp focus, among many other things, the issue of racism in that country.

The marauding invaders who forcefully entered the building, vandalising sections thereof, violently attacked law-enforcement officers and threatened elected officials, seems to have been treated with kid gloves by the security forces.

Contrast that with the heavy-boots approach used by the police against members of the black community and the Black Lives Matter movement who have stepped up their protest in recent months against the harsh treatment many blacks have experienced at the hands of the police.

This contrast in behaviour by law enforcers has led some to conclude, including President-elect Joe Biden and former President Barack Obama, that if those who marched on the capital last week were black, the reaction of the security forces would have been far more strident.

The growing concern by well-thinking persons in the US and elsewhere regarding the deepening of institutionalised racism under the Trump regime has brought back to memory the days of apartheid in South Africa and the struggles by Jamaicans and others in the Caribbean in support of the fight against apartheid.

One tool of engagement in that fight was an international sporting embargo that was implemented in 1968 when the International Conference of Human Rights recommended the exclusion of South Africa from the membership of international sports federations and associations because of the practice of racial discrimination in sports. This eventually led to the Gleneagles Agreement in 1977, which discouraged all sporting links with South Africa.

In these efforts, Jamaica led from the front. We were the first country to declare a trade embargo against South Africa in 1957. It was, therefore, not surprising when the Jamaican Government and other governments in the region imposed a ban for life against twenty cricketers who sneaked out of the region, in the early 1980s, to play cricket in South Africa in return for huge sums of ‘blood money’ paid by the South African cricket regime. The ban meant that they were not able to play test cricket and in some countries of the region not able to play regional or club cricket. Their isolation from cricket affected their lives in different ways.

EX-CRICKETERS AND SOUTH AFRICA

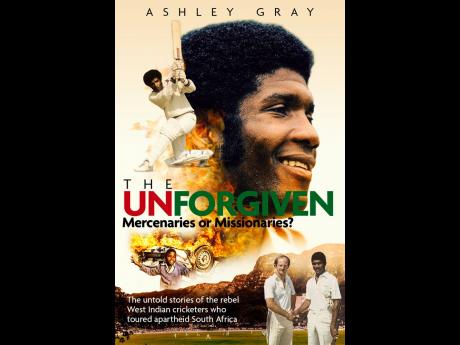

‘The untold stories of the rebel West Indian cricketers who toured apartheid South Africa’ are revealed in a recently published and well-written book titled The Unforgiven – Mercenaries or Missionaries, by leading Australian journalist Ashley Gray.

Gray, using personal interviews with the majority of the ex-players, gives his readers deep insight into the personal state and condition of all 20 cricketers who turned their backs on local and international regulations in order to play in apartheid South Africa.

Needless to say, the governments and the people of the region were incensed by the decision of the players. The late Roy Fredricks, a past player himself, who was at the time, the Minister of Youth, Sport and Culture in Guyana, suggested that the renegade players should “not cause further discomfort to the West Indian population by attempting to live among us”. Clive Lloyd described the tours as “an affront to the black man throughout the world”. Vivian Richards said that he would “rather die than lay down my dignity”, the way they had done.

The 20 players involved were Lawrence Rowe, Herbert Chang, Richard Austin, Everton Mattis, and Ray Wynter (Jamaica); Alvin Kallicharran, Faoud Bacchus, Monte Lynch, and Colin Croft (Guyana); Derick Parry (St Kitts and Nevis), Bernard Julian (Trinidad); Albert Padmore, David Murray, Harley Alleyne, Ezra Moseley, Alvin Greenidge, Emmerson Trotman, Collis King, Sylvester Clarke, and Franklyn Stephenson (Barbados).

According to Gray, “Some coped with ostracism by deserting their homelands. Others sought refuge in drugs and religion.”

In relation to the five Jamaicans who went, Richard Austin is no longer with us, Rowe and Mattis live in the US while Chang, who is battling mental-health challenges, and Wynter, live in Jamaica.

Of the others, regrettably, as is the case with Austin, Bernard Julian and Sylvester Clark have passed.

REASONS FOR GOING TO SOUTH AFRICA

In their interviews with Gray, the cricketers gave different reasons for going to South Africa. Some claimed that they went to help black people to understand what they could achieve as blacks, others claimed that they went for the hefty sums of money that they were paid, while others claimed that their career had come to an end as far as playing for the West Indies was concerned.

We must recall that these cricketers could not have been able to move freely in South Africa unless they were granted the status of ‘honorary whites’. That designation allowed them the privilege of venturing into areas reserved for those who were white. We must also recall that at the time those who were in the forefront of fighting against apartheid stated their objection to the cricketers travelling to South Africa.

Further, it was very clear at the time, that the primary aim of the organisers, who all supported apartheid, was to further legitimise apartheid, by getting black cricketers to play in South Africa.

Those among us who are calling for the ex-cricketers to be forgiven, must read Gray’s book to understand that the vast majority of these ex-players, to date, have expressed no regret in going to South Africa. Everton Mattis, however, told Gray, that it was the biggest mistake of his life.

Rowe, who captained the rebel side in 1983, still cannot understand why players such as Michael Holding, Clive Lloyd, Vivian Richards and Jeffery Dujon were so strident in their criticism of him and the others for going to South Africa.

Rowe’s response is that ‘I believe that these guys were so jealous of what I was. A lot of people describe me in Jamaica as what Usain Bolt is now. Few of us reach that level, that kind of iconic level from the public. Mikey never got that. I don’t know why’. Rowe singled out Holding because he did not mince words when he said that ‘if they were offered enough money, they would probably agree to wear chains’.

Alvin Kallicharran, Rowe’s deputy captain, who was a key figure in the conceptualisation of the tours, told Gray that he would not apologise for going because, ‘he has nothing to be guilty about’.

Franklyn Stephenson, then only twenty-three, and the youngest player in the team, remains adamant that the visit to South Africa helped to advance the cause of ‘freedom’ in that country. Monty Lynch, without reservation, disclosed that he has no remorse and Ray Wynter, like Stephenson, is of the view that they, ‘played a role in ending apartheid’.

NO TO RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

It is very clear, based on what has been unearthed by Gray, that many of the ex-cricketers were, and still are, at sea, regarding the impact of apartheid on the majority of the people of South Africa, where racial discrimination was an organised way of life, until 1994, when the first democratic elections were held, and Nelson Mandela became the president of post-apartheid South Africa.

The tours to South Africa took place thirty-eight years ago. Fast forward to 2021 where the United States, which professes to be the greatest democracy on earth has, by the policies and words of President Trump, given racism new life.

Unlike the rebel cricketers, we cannot remain silent or give support to those who seek to promote any form of racial discrimination.

- Delano Franklyn is attorney-at-law and former PNP senator and minister of state. Send feedback to delanofranklyn@gmail.com