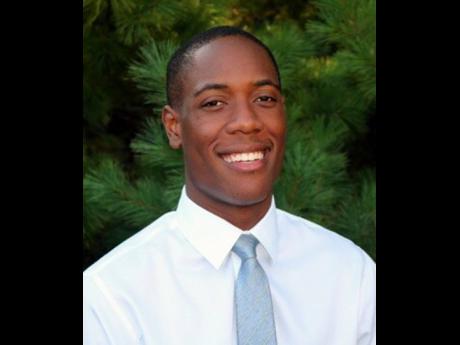

Stefan Richards | Reclaim our stolen boots!

At the recent launch of the Special Reparation Issue of the Journal, Social and Economic Studies, hosted by the Centre of Reparation Research, in collaboration with the Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, Stefan Richards responded on behalf of the other contributors. In “Reparation Conversations”, we bring you a young man’s moving account of his journey to writing and publishing his essay and his surprise that reparations can be a divisive topic among the victims.

Reparations is a means of gaining justice for the centuries of torment and subjugation of our people. Not only are reparations morally sound, but through my study, I found that reparation can be financially sustainable in the long term. Throughout this journal, what we are also talking about is our shared history, our shared memory, and how it has come to shape our present, our future, even our perception of who we are. When I began preparing this brief reflection, I spent so many late nights and early mornings thinking about where to start. Our history is so heavy and so vast. Eventually, I began thinking about the moments and experiences that shaped my perception of reparations from relative disinterest to staunch proponent. Today, I will share some of them with you.

I remember being seven and foreign-minded. I could not wait to travel the world and, hopefully, trade Jamaica for somewhere up North. I used to tell people I was born in Miami. Toys R’ Us was probably my biggest incentive at the time to move to the United States, but even then as a child, I saw the differences between an underdeveloped and developed country though I had been unable to articulate it. I remember when I began travelling as a teenager and finally moved to the UK to study at age 17. I remember when that yearning to be ‘in foreign’ turned to resentment; resentment for the excess and waste all around me while I tried to save every last scandal bag and Ziploc I used; resentment for having to trade warm weather for frigid winters just to get an education that would be seen as more valuable globally; resentment for leaving my family, my community, and the only place I have ever called home to reside in lonely cities; resentment for the centuries of robbery and treachery that inevitably resulted in an underdeveloped global South and prosperous metropoles, full of immigrants trying to reclaim their wealth and heritage, even their artefacts.

I remember visiting Musée d’Aquitaine in Bordeaux, France. The tour guide spoke of Bordeaux’s past riches, beautiful architecture, while boasting about the fact that most of these riches came from Bordeaux’s heyday as a primary port in the Trans-Atlantic Trade in Africans, commonly known as the slave trade. That is to say, most of these riches came through the trading of humans who look just like me. When the tour guide asserted this, my classmates looked to me with pity and concern as the only black person in the group. But what was I supposed to do? Tell them it’s OK? That I’m not angered at the sight of all this opulence while my country, in many ways the source of the riches, suffers endlessly?

DIFFICULT TO GRAPPLE

I remember reading La Condition Noire by Pap Ndiaye, an excellent study that looks into the social costs of being black in the French colonial empire. I lived with host parents in Paris at the time, and while I was reading the book in the living room one evening, my host parent’s son asked me, “Isn’t it hard to read that?” I hadn’t understood the question, so I plainly responded, “Not really, my French is getting better.” However, I later understood that he believed that the atrocities against black people described in the book may have been too difficult for me to grapple with. As I thought about it I wondered, shouldn’t it be hard for the children of the oppressors, the ones who have caused so much pain to several continents, to read about their own atrocities?

I remember applying to an internship in Jamaica several years ago. The company requested that I submit a PowerPoint presentation on a topic about which I was passionate. Who told me to do a presentation on reparations? Naively, I assumed that this topic would be received warmly. Yet, a couple weeks into the internship, one of my supervisors told me jokingly that they had hired me “despite my presentation”. She found it strange and did not understand how one could be passionate about something that “didn’t make sense”. In that moment, I was confused. I had not considered that reparations could be a divisive topic among the victims.

Finally, I remember writing my article published in the journal, titled “Can Reparations Buy Growth? The Impact of Reparations Payments on Growth and Sustainable Development”, and I encourage you to read it. I wrote it as undergraduate research. My adviser thought I was wasting my time. He said that I should aim to write something interesting that may be published one day, not just something I, myself, found interesting. After what can only be described as a protracted academic war, I was granted permission to complete this research as long as it was never called a thesis. Today, I am grateful to everyone here who has found value in creating and sharing knowledge on how to achieve justice for our ancestors, our grandparents, ourselves.

So as we sit here and discuss reparations, I do not take this space and opportunity for granted. We are discussing lives and livelihoods lost; lives and livelihoods that in many cases never even started. A continent is in mourning for what was, and more importantly, what could have been had it not been for the violence and hate. For all of this, we need justice, and there is no justice without reparations.

The US recently celebrated Martin Luther King Jr and his legacy. One of his messages has always stood out to me. He stated: “It’s all right to tell a man to lift himself by his own bootstraps, but it is cruel to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps.” The time has come for us to reclaim our stolen boots.

I would like to thank the organisers from the Centre for Reparation Research and the Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies for providing a dedicated space for us to discuss reparations, a topic that deserves much more attention than it currently receives. I would also like to thank Professor Sir Hilary Beckles and Professor Verene Shepherd for continuing to champion the cause of reparations across the Caribbean and grounding the topic firmly in academia. In the same vein, a big thank you to each person who contributed to this publication! Finally, I would like to thank the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, David Cameron, for visiting Jamaica and telling us to “move on”. His statement was a wake-up call, a reminder that injustice is not experienced equally and that colonialism never really ended.

- Stefan Richards is a network scholar at the CRR and a junior counsellor at the Office of the Caribbean Executive Director at the Inter-American Development Bank. Send feedback to reparation.research@uwimona.edu.jm.