Haunted by 1980 | ‘Demon’ Seaga, ‘dangerous’ Manley: tales of the 1980 election

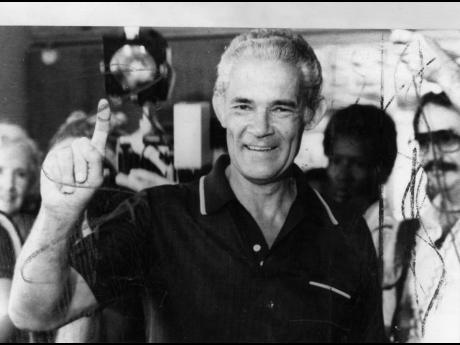

The historic electoral whupping of the People’s National Party (PNP) of October 30, 1980, at the hands of the Edward Seaga-led Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) still evokes raw emotions today.

Sixty seats were contested and the JLP won 51.

That victory symbolised the sound rejection of socialism and communism politics with which the flamboyant Michael Manley flirted during the time of the Cold War.

At stake were the fledging democratic traditions of Jamaica against the so-called push to liberate Jamaicans and the promise to equalise a society characterised by a deep divide between classes of people.

The victory by the JLP placed Jamaica firmly in the corner of the West and meant that Jamaica, for at least a decade, would stand against any influence of socialism and communism.

In the year of the 40th anniversary of that famous election, the JLP trounced the PNP in like fashion at the polls, which has pushed the party into a tailspin, searching for a new leader, a renewed philosophy, and new energy.

Politician historian and former PNP senator Delano Franklyn recalled that Manley and Seaga went after each other aggressively in rhetorical duels that morphed into pitched battles among supporters.

“Because the campaign during that period of time was within an ideological framework and philosophical framework and you had Michael Manley on one side who was a person who campaigned hard – he was extremely convinced, deeply committed – and on the other hand, you had Seaga who was equally passionate to the belief that he held dear.

“It was friction! Friction and sparks during that period of time,” recalled Franklyn in an interview with The Gleaner.

Franklyn asserted that the messaging from the JLP was sharp, aggressive, and centred around unshackling the country from the Manley regime. Seaga and the JLP had spelt out in precise language why socialism and communism was dangerous for Jamaica.

“The deliverance was about the Jamaica Labour Party being here to deliver you from communism. Being here to deliver you from a Government that wanted to take away your rights,” he said.

“The platform engagement at that time excited Jamaican people. It kept young people glued to their television and fully engaged in the process,” Franklyn added as he emphasised how the two leaders were poles apart in the philosophies.

And as such, Manley and Seaga challenged each other in the charged political atmosphere characterised by guns, wailing, and bloodshed.

“Manley was of the view that a demon had entered the leadership of Jamaican party political representation. Manley was of the view that Mr Seaga was more out to divide than to unite,” Franklyn, also an attorney-at-law, said.

But Seaga had his own view of Manley and went to great lengths to warn the masses about Manley’s ideological flirtations.

Franklyn said that Seaga told the people that Manley was friends with former Cuban President Fidel Castro and members of the defunct Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and was dangerous for Jamaica.

“He was very aggressive on the party’s political front. He said that you do not want a party in Jamaica that represents democratic socialism ... that we must stand up – ‘stand up when you hear the bell’, you must stand up against that type of politics,” Franklyn said.

The former senator said that Seaga’s firebrand style drove fear into his opponents and critics as he went about trampling the seedlings of communism, which he thought were being given sunlight to take root in the young democracy – less than two decades into independence.

“People were afraid! He drove fear into a lot of persons in Jamaica at that time, and that fear manifested when he became prime minister,” Franklyn stated.

“Seaga’s campaign was very aggressive. It was aggressive on the economic front. The argument was the PNP had failed Jamaica, and Jamaica required a leader and a kind of party that could build back the economic base of Jamaica,” he added.

Apart from those two primary actors, Franklyn recalled that many community groups, unions, and activist organisations had helped to shape the political conversation at the time as the country was roiled by strife.

“People were not afraid to express themselves despite the violence that was taking place. They were either in support of the PNP or the Jamaica Labour Party. It was, therefore, not by chance that the turnout in the 1980 elections reflected 82 per cent,” he said.

That sort of engagement has been absent from the political process still and so, too, the high voter turnout resulting.

In the September 3 polls, 37 per cent of registered voters turned out to vote, the lowest ratio registered since Independence. Although the outbreak of the coronavirus might have had some impact, the trend lines of political apathy have been steady since the late 1990s.

Franklyn believes that voter engagement has been dampened by the absence of clear philosophical differences between the two main political parties.

“Connected to that is the absence of ideological and political discourse. Absent from the politics of today against that time is the involvement of our people nationally. Politics is more now about individualism than nationalism,” said Franklyn.

“The third element that is missing from the politics now against then was at that time, you had hope despite the foment of the politics.”