Rising above the ‘blood curfew’ - Poor, black, unattached yearn for better days in bitter inner-city enclaves

Dangerous thorns spring aplenty in the gritty inner-city community of Rose Gardens, nested inside the crime-infested community of Southside in the capital city, sitting within the larger infestations in Kingston known as Spoilers. Robert Calvert...

Dangerous thorns spring aplenty in the gritty inner-city community of Rose Gardens, nested inside the crime-infested community of Southside in the capital city, sitting within the larger infestations in Kingston known as Spoilers.

Robert Calvert was brought up in this area, where the deck is heavily stacked against the young, unskilled, uneducated males of the community and a life of crime is almost a certainty.

He fits the bill perfectly and has never smelled any roses, but he has defied the odds so far.

Frequent relocation is a common feature among inner-city residents, but since Calvert’s family moved from Wildman Street at age four, they have called Rose Gardens home for more than two decades.

Calvert told The Sunday Gleaner last week that at 28 years old, he could have been a “veteran gunman” had he decided to walk that path when he left school in 2010.

Coincidentally, his last day at school was the day a police-military operation was launched in Tivoli Gardens to capture and extradite Christopher ‘Dudus’ Coke on gun and drug-running charges, on which he was later convicted in the United States.

“Is the first time I was seeing anything like dat. Helicopter all over the place, police, soldiers, fire. The whole place was under lockdown and everybody frightened ’cause nobody neva really know what a happen or what was going to happen,” he recounted.

That day was May 24, 2010. And despite having a year to go at St Andrew Technical High, it was the last time he set foot in school.

“I didn’t even do my exams. I leave school that time and never go back,” Calvert said, his voice a mixture of sadness and finality.

... Voiceless, powerless with grim view

Robert Calvert is still young. His dark complexion shows an abundance of melanin in his 5’8”, 170-pound frame.

He describes himself as poor, but surviving on a “better salary” than his regular “janitor workers”.

He is disadvantaged, uneducated and skilled at nothing and powerless because he calls no shots.

Voiceless on the fringes, he doesn’t even believe his vote counts, as desperate circumstances have driven may residents to offer their ‘X’s to the highest bidder at election time.

But Calvert is no criminal. He has never been named a suspect in a crime, arrested or charged with anything, although he had considered robbing people before.

He could have also committed murder many times. He could have also used a knife to inflict serious wound, except, as he puts it, “all the people who I know do dem something deh either at May Pen Cemetery or Dovecot, and mi nuh know if dem resting peacefully”.

The two graveyards hold the bodies of many youth with unfulfilled potential from areas like Spoilers – fragile umbrella covering communities within the boundaries of North and East streets, Camp Road and East Queen Street. It is a violent social and political ecosystem which bear strange fruits like those Billie Holiday immortalised in song showing black people being lynched in the Southern United States.

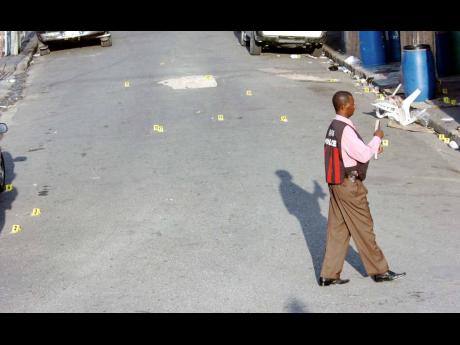

In Kingston Central, warring factions are currently peppering each other with bullets and wallowing in the aftermath of the bloodbaths.

Both Rose Gardens in Southside and Wildman Street, where Calvert grew up, could fit perfectly into scores of other similar communities across the city, and a number of areas in several rural parishes.

In these areas, people are sometimes murdered in multiples for an unspoken ‘diss’ – perceived or real disrespect.

They are the urban poor – powerless, unemployed and their existence is where decaying infrastructure and a desert of human and social biology is their only view.

The view is ugly.

So, too, are the hearts of many, especially men and women Calvert’s age who spew vulgarity and crudeness even in cordial conversations.

“I am a wiper. I have experience doing it. I do janitor work for years, and best of all, I love it. I love it, man, ‘cause I can do it good and mi like when mi do it people say it done properly,” Calvert beamed with pride, celebrating his humble job, which is often greeted with upturned noses by many, including the unemployed.

... Walking a straight path

Robert Calvert is on his fifth job at FLOW – the one with the highest upgrade and best pay.

The son of a street cleaner and mechanic/labourer father, Calvert is among nine children from both parents, and has worked at Creamy, Cal’s, Big Joe and Manpower – all on janitorial contracts.

Stating that he said he has received “fights” from supervisors, he has also admitted that being absent from work for three days without telling his supervisor was “irresponsible”. Still, he admitted to have learnt many lessons about “human nature”.

He is currently a road team customer service representative for telecoms company FLOW and proudly donned his uniform for the interview.

Political activism, he said, brought him into the path of Imani Duncan-Price, the losing Kingston Central candidate in the general election last year. He saluted her for efforts he described as “going above and beyond to help me and other people find work”.

“Mi nuh want nuh handout. Mi want fi work for what I want, and Imani help me,” he said, adding that he has returned the favour by helping to assist other persons with employment.

He has, so far, survived the pressure on the inner-city man to sow oats everywhere, have many children, or be called a ‘gelding’ – a man who cannot impregnate a woman.

Although his “name has been called on one child”, Calvert said he has no contact for the mother, who gave the child her surname.

He is not a genius, but is smart enough to stay away from crime and has vowed to shun criminality and all of its branches.

He has lost many persons, including close friends, to violence in the community.

“Mi nah go inna dat. I love to work. I am a talented person. I love life. I can read and write. Gun ting a nuh fi me. Mi caan manage dat. And I try to stay around people who can help me get opportunities,” he told The Sunday Gleaner.

He did not disclose where he currently sleeps, but he, like many young men, have been warned to stay away from Spoilers, which is “running hot”.

“Gunfire tun up,” he said.

When it is not hot, “it’s a nice party spot where the people a mostly all family and everybody know everybody in dem likkle community. Football talents and netball, girls”.

... A different type of fight

A trip to Southside will yield the customary pairs of eyes of women peering from behind walls, and the sight of a man or child sitting on the avenue, eyes darting up and down. These are the eyes of the community. Nothing goes unnoticed.

Old cars, dilapidated buildings, discarded furniture, uncollected garbage, half-dressed females and the exposed underwear of males are part of the view.

Calvert does not know the reason for the current crime wave, neither do many other residents of the community.

But it could be anything.

“Man and man inna quarrel over gambling, and man and woman ova de same ting. Man and man a play football and get kick and don’t like it and go for him gun. Somebody say somebody get diss, but most times is over money. Them go fi gun and next thing the whole place under blood curfew.”

Calvert knows black people life and history “very hard”, but believes the current bloody period in Jamaica is just as bad “when people was a fight fi dem rights”.

With February being recognised as Black History Month, he acknowledged that they were also not making things easier for themselves.

“People fi know demselves. Sometimes a family a kill family. Look how much news we hear about family a kill family. It nuh right. People can live better,” he stated.

Today’s wars and those of the past were different, he acknowledged, however.

“Back in de day black people fight system fi better. Now people a fight dem one another. That caan be for better. So we have to stop fight one another and fight systems. We must start live better. We better dan dis, enuh. Mi know me better dan dat. That’s why mi nuh involved. No sah,” he said, simplicity and determination bellowing from his voice.

As we spoke by the waterfront in downtown Kingston last week, the large expanse of water provided the backdrop for the interview as seagulls lurking in the distance cackled with life as they received a generous gift of fish entrails from a nearby vendor.

Calvert believes his current employment has caused him to develop wings, as he has “become quite a good road team member”. He wants to be taught to fish, so he can fly, but he also want the same for poor, black, disadvantaged but honest persons, like himself, in all communities.

“Young people just need a chance and might be nuff, nuff patience. That’s what FLOW give me, and mi using that fi help myself so mi don’t have to be begging people for anything,” he told The Sunday Gleaner.