How freakish fate turned jobless Jamaican into global pioneering inventor

Seventy-year-old Jamaican, Glen McFarlane, is partly credited for the pristine quality people around the world experience when they watch high-definition television (HDTV). Back in 1991, he was hired by LEMO in England to start the operations to...

Seventy-year-old Jamaican, Glen McFarlane, is partly credited for the pristine quality people around the world experience when they watch high-definition television (HDTV).

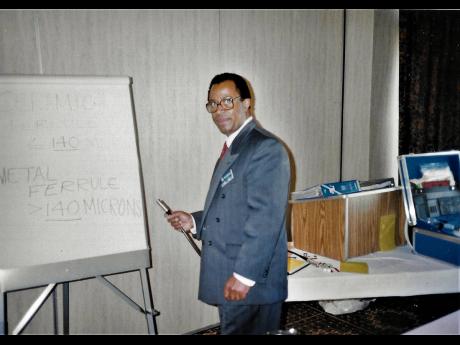

Back in 1991, he was hired by LEMO in England to start the operations to move from traditional copper cables to fibre optics, which would offer an improvement from screens displaying excessive grain, approximate colours, and irregular slow-motion replay.

That work, dating back to three decades ago, was awarded a 2020 Technology and Engineering Emmy Award in February 2021 for standardisation and commercialisation of television – broadcast, hybrid electrical, and fibre-optic camera cable and connectors.

“It is an incredible accolade, and I feel very, very proud of this achievement,” McFarlane said in a recent Gleaner interview.

The retired fibre-optics expert was born in Rock Spring, Trelawny, and at six months old - for reasons still unknown to him - his mother left and went to Kingston.

He became quite ill with an infection in his eyes, which reduced his vision.

“It's still good enough and I am allowed to drive in the UK,” he said.

A young McFarlane moved to live with his father's family, and at age seven, was placed in the care of aunt Phyllis McFarlane, who was then a deputy head teacher of Duhaney Park Primary who had no children.

“She became my mother, and I grew up with her,” he said, adding that they resided in different parishes.

He attended May Pen Secondary School and completed his education at St Andrew Technical High School, where he sat O Level examinations.

As the seven-year-old experimented in using old radio batteries to do lighting around the house, his aunt took note of his potential. He later moved in with an uncle in London when he was 18 and qualified for entry to Imperial College at the University of London.

Upon completing a BSc in physics and engineering, McFarlane had plans to return to Jamaica, but fate would have it otherwise.

McFarlane accompanied his friend to a job centre, and while his pal was being interviewed, a woman approached him and asked him about his qualifications.

“I told her, and I guess she thought I was looking for a job, so she told me not to move and said that she knows a company. Next thing I knew, they sent a car out to get me,” he said.

He landed a job with Johnson Matthey, one of the largest producers of precious metals in the world. And so he cancelled his flight, secured British citizenship, and became an engineer.

McFarlane worked in the division specialising in safety devices, and one of his first inventions was a device used on the space shuttle back in the 1980s to prevent tyres from exploding during landing.

That was just the beginning for the Jamaican, whose intellect and skills have put him at the forefront of the development of inventions or solutions and becoming a manager by age 26.

In early 1995, LEMO's Japanese subsidiary confirmed a request that was still confidential – Japanese camera manufacturers wanted to broadcast the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games in high definition.

They needed a connector to make this great premiere a success.

Together with LEMO's product director, McFarlane designed a model that met the brief – the 3K.93C – and after several trips back and forth and intense testing, the connector was sent to Japan to be tested by Panasonic and Sony.

McFarlane and the technical director, Jean-Claude Hubert, travelled to Tokyo to receive the test results where the Japanese found one weak point, which was mechanical: the anchoring device had to be able to stop a camera from falling from a platform.

They reacted immediately and worked through the night in their hotel room to create a new system, followed by technical drawings, a new prototype, and tests.

McFarlane said the Japanese were impressed, and a few months later, LEMO learned that its solution had been selected.

He recalled watching the opening ceremony of the Olympics with his fingers crossed.

There were no breakdowns or problems, and after the Olympics, the connectors and cables were sent to Japan to be tested.

The following year, the 3K.93C series was officially chosen by Japanese television as the standard for high definition.

Soon enough, American television made it its own, the Europeans in 1999, and today, the 3K.93C is the global standard.

Sharing another project he worked on, McFarlane recalled a woman in the United States washing the cylinder of a SodaStream machine with hot water when the pressure rose and it exploded, killing her.

The company to which he was employed was approached for a solution that would prevent a similar tragedy from occurring.

“It's used on these dispensers even today, right across the world, and this was about 40 years ago,” he said.

While working at LEMO, he also developed a sensor for monitoring premature babies while they are being born.

“While the baby is in the birth canal, the doctors attach the sensor to the baby's forehead and can monitor the baby's vital signs while it is being born,” he said, adding that the invention was taken over by Johnson & Johnson and has saved thousands of babies' lives over the years.

Throughout his career, he worked at Philips, was the managing director of JDS Uniphase, and owner of a small part of the company when operations were moved to its headquarters in Canada.

McFarlane told The Gleaner that one of his greatest pleasures in life was inviting his aunt Phyllis to visit and stay with him in England while he was a managing director.

“She stayed with me for 12 weeks, and on one of my return visits to Jamaica, one of her neighbours told me how proud she was of her son's achievement,” he said, adding that she passed in 2015.

Over the years, he balanced working with family life with Kay, his wife of 44 years, and three daughters, Joanna, Davina, and Sarah.

Since his retirement in 2005, McFarlane has done quite a lot of consulting and is currently working on a major personal project, the details of which he is keeping close to his chest because it is in the patenting process.