Anthony Clayton | Policy options for COVID-19 in Jamaica (Part 1)

WITH FLU, it usually takes about three days from infection to becoming ill. With COVID-19, it averages five or six days, but it can be up to two weeks, and some people who get the virus don’t develop any symptoms. About 80 per cent of those infected will have a mild illness, about 15 per cent will suffer a more severe illness, and about five per cent will become critically ill.

In the mild cases, people might need to rest for a week or two, the more severe cases may require hospitalisation and oxygen support, and the critical cases will require admission to an intensive care unit to try to prevent serious complications such as organ failure.

The reason why COVID-19 is now a global pandemic is that most of the people who are infected don’t get very ill, and many of them don’t stay at home. These are the people who are spreading the virus. As a result, the number of cases in New York is now doubling every five days, which means that it takes just eight weeks to go from 10 to 40,000 cases.

The key variable is the reproduction number (R), which is a measure of how many other people, on average, someone carrying a virus will infect. If R is less than one, the number of cases will shrink. If R is greater than one, there will be an outbreak.

Seasonal flu has an R value of 1.4; COVID-19 has an R value ofaround 2.5. In order to control the pandemic, therefore, it is essential to reduce the COVID-19 R below one.

R depends on a number of variables, such as how easily the virus is passed on, how many susceptible people there are in the population, the latency period (how long a person can be infectious without showing symptoms), the duration of the illness, social circumstances (the number of people that an infected person meets), human behaviour (including compliance with health and safety advice), and ethics (the extent to which people change their behaviour to protect others). The biological factors are not amenable to policy initiatives, but the social, behavioural and ethical variables are.

For someone young and healthy, the chances of dying from COVID-19 might be about 0.5 per cent, but for those over 64, it is probably closer to five per cent, and will be higher still if they have high blood pressure, heart disease or diabetes (unfortunately, these conditions are relatively common in Jamaica).

People in countries with good healthcare systems are probably more likely to survive than people in countries with limited resources, so the most vulnerable group in the world are older people with existing health problems in low- and middle-income countries.

GOVERNMENT ACTING SWIFTLY

The number of people who will be infected largely depends on whether a government acts swiftly and decisively. With an uncontrolled outbreak, it could be 60 per cent of the population.

The population of Jamaica is 2.96 million. An uncontrolled outbreak scenario in which 60 per cent become infected would gfsult in nearly 1.8 million cases. Of these, about 1.4 million might have to take a week or two off work, nearly 267,000 could require hospitalisation and oxygen support, and nearly 89,000 could require intensive care, giving a combined total of over 355,000 who would need hospitalisation.

This would, of course, overwhelm the healthcare system. There are fewer than 5,500 hospital beds in Jamaica, and only a small fraction of those are suitable for intensive care. If all those people were to require hospitalisation over a short period, Jamaica would need about 65 times more hospital beds than it has now.

If the healthcare system is swamped by the above-mentioned number of cases, it will mean triage to determine which cases will receive treatment, and who will be left to die. In most cases, it will be the sick and elderly who will be left to die, partly because their needs will be greater (which means that they will consume the medical resources that could support a larger number of people with a less serious infection) and partly because their prognoses will be significantly worse anyway.

In a situation of absolute scarcity of essential medical resources, the way to reduce the total harm to the population is to focus those resources primarily on the 15 per cent who are seriously ill, but who have a good chance of returning to health.

FLATTEN THE CURVE

There are promising signs that a vaccine will be developed soon, but clinical trials (which are necessary to ensure that a vaccine does not itself cause illness) usually take at least 12-18 months.

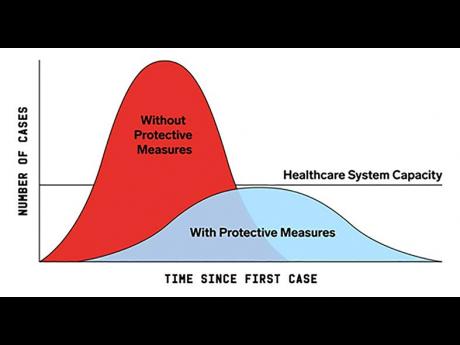

The key goal of public policy, therefore, is to reduce the insupportable peak load on the healthcare system by spreading the number of cases out over time. This means using all means possible (exhortations about handwashing and social distancing, closure of schools and public places, and so on) -- not to prevent the infection of the population, but to ensure that it happens as slowly as possible. This is represented in the chart, which shows that the aim of intervention is to ‘flatten the curve’, that is, spread the total number of cases over a longer period, primarily in order to keep the load on the healthcare system below its maximum capacity.

If some of the impact can be deferred in this way until a vaccine becomes available, far fewer people will die and Jamaica might be able to escape the worst effects of COVID-19.

Until then, the only possible course of action is to focus on the policies and interventions that have the best chance of bringing about the necessary behavioural changes.

FOUR KEY GROUPS

These interventions have to be focused on four key groups:

1. People who can work from home, and who can therefore self-isolate. This group includes, for example, academics, administrators and government employees.

2. People whose jobs require them to be at their place of work. This includes police and security forces, technicians needed to maintain the electricity grid and communications networks, cleaners and garbage collectors, the logistics staff who manage shipping, and the employees at pharmacies and grocery stores needed to deliver essential supplies to the population.

3. People whose livelihood depends on their working outside of their homes. This group includes, for example, street vendors and others in the informal sector.

4. The non-economically active segment of the population. This includes dependents, infants, and those who are elderly, frail, ill or house-bound.

IMPORTANT INTERVENTIONS

The most important interventions for each group are as follows:

1. Anyone who can work from home should now be required to do so.

2. All employers should be required to equip their staff with masks, gloves and hand sanitisers, and ensure that they are fully compliant with Ministry of Health and Wellness guidelines.

3. The third group is the most problematic. Many of these people will not be able to survive for long without an income, and cannot sit at home when their children are hungry.

4. The fourth group is also problematic, but for different reasons; the need here is to ensure that caregivers can continue to look after children and dependents, and that the elderly and frail can self-quarantine at home.

Part Two will examine the policy options for dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, including how to limit the damage to the economy and how to deliver the necessary support to the most at-risk groups in the most efficient and affordable way possible.]

Professor Anthony Clayton, CD, Institute for Sustainable Development, The University of the West Indies. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com