Mazola dissects ‘Messianic Parables’

Last month, patrons had been mulling over Kenyan Jamaican artist Mazola wa Mwashigandhi’s ‘Messianic Parables’ in his ‘Playground’ studio at Craig Hill in St Andrew. “Messianic Parables is a visual and poetic interrogation and reinterpretation of ancient parables as seen through the eyes of a child of rainmakers,” the mission statement said.

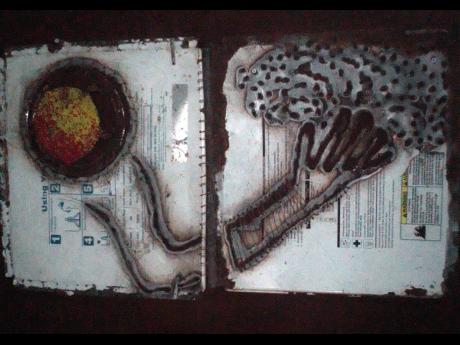

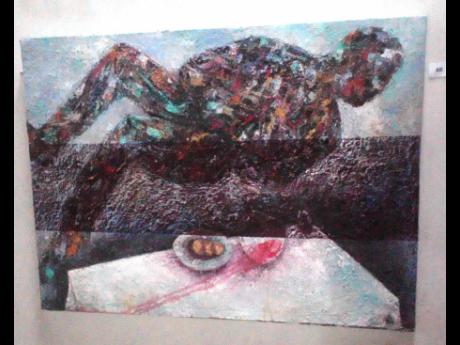

On display were 28 multimedia pieces inclusive of paintings, sculptures, installations, and assemblages, some of which are entitled by biblical references such as, ‘Feeding the multitude’, ‘Stairway to heaven’, ‘The hand that giveth’, ‘Resurrection’, ‘Walking on water’, ‘Book of life’, ‘Seven times seventy-seven’, ‘Crown of Thorn’, and ‘The Second cock crow’.

He is using art to question and reinterpret biblical stories and parables told about, and within, the context of the gospel of the messiah, Jesus Christ. Though he was brought up a Christian, he doesn’t belong to any one faith, and he’s now translating the parables of the messiah in his own way.

Coming from a lineage of rainmakers, Mazola, as he is known in the artistic community in Jamaica, dedicated the show to his father, Silas, who died in 2005, and whom he did not mourn at the time. In African traditions, rainmakers are people who perform sacrifices to get rain.

And Mazola told the story of how Christianity superimposed its beliefs and practices over traditional ones in his village of Mlambenyi in Kenya. Even the local church was built over their traditional shrine.

TAKING OVER

“In a way they are taking over this place, and they are killing whatever you are doing, and that is exactly what happened,” he told Arts and Education. Even in his own family it had created conflict and destroyed the relationship between his grandfather and father.

Each of his grandfather’s children had a charm to protect them from evil practices. When his father was about 12 years old, the boy requested his charm from his grandfather. As soon as he had got it, he threw it into a pit latrine, saying that he didn’t need it since he had found Jesus.

The rift that that act created became so wide that his father was forced to leave home to fend for himself in Mombasa, Kenya’s oldest and second-largest city. That was one instance in which the stories/parables of the messiah can be interpreted in a negative way. Thus, the essence of the show is embedded in the religious, the familial, and the personal.

“It is in relation to my dad’s life and what he has taught me,” Mazola shared. Yet there were other shows that seemed to have been connected to the passing of a family member. The first in 1998, his very first show in Jamaica, was dedicated to a brother who died in a road accident.

His mother passed in 2010, also when he had a show. “So I’ve been doing these things a long time. I’ve had to find my own way of grieving, if it is grieving, maybe to celebrate their lives,” he said in retrospect. “So a sort of inspiration come from them.”

His own personal motivation came when his right arm, the more dominant, was broken. It was a very serious injury that required ‘save it or lose it’ surgery. To fix it, the surgeons knocked him out. He referred to his waking up from the anaesthetics as his “resurrection”, depicted in a painting of the same name. And things got really interesting when a surgeon requested a sculpture of a black messiah.

Mazola calls the injured arm his “bionic” arm, which is now doing more work than it did before the injury. And while it was being healed, he did not keep a pity party. His left arm chipped in and produced a series of watercolour collages called ‘Meditations on my broken hand’.

The father of three is a storyteller, and he has revisited biblical parables, telling stories with his work, which he said are not to be viewed at face value. You have to do your own interpretation. They are intended to provoke thought even about messianic parables.

“I tell stories, and even when you look at my work, my work takes something very complex and make it so simple, like a child, and when it becomes simple, it becomes complex again,” he said.