Book Review | A story of resilience

Author Barbara Ellis chronicles a transitional period in the black experience. It is the postslavery era, but freedom brings a new set of challenges.

An African Journey is a captivating sequel that details slavery's aftermath, the curious events surrounding its abolition, and the search for meaning after manumission. Throughout, the resourcefulness of a people is evident.

That blacks continued to struggle despite their new-found status is not unexpected, their economic plight exacerbated by the influx of indentured servants in several West Indies colonies leading to competition and lower commodity prices. Handicapped by less than ideal terrain to grow produce, harsh weather conditions, high taxes, and lack of political representation, families were continually weighed down by harsh colonial rule.

After 1838, migration for work outside their native land was seen by many workers as the solution to abject poverty. Ellis explains, "They went to Panama to construct the railway, to the banana plantation of Costa Rica and Cuba ... Some went to the oilfields of Venezuela, Aruba, Trinidad seeking work.

"Meanwhile living condition worsened. Many of the landowning Africans were also affected by drought, hurricanes, increased taxes, and rising costs of everyday essentials; they could not pay their taxes ... the jobless workers scavenged on abandoned estates for food, the police arrested them and took them to court ... The community leaders encouraged them to express their grievances to the assembly, the queen and the government."

MORANT BAY REBLLION

A suffocating economic climate led to the Morant Bay Revolt. The brutal, retaliatory crackdown on protests led to the summary execution of hundreds, including the principal actors.

The Crown responded to this anguish with cosmetic changes to the political apparatus. Still, veritable access to power was off-limits to these descendants of former slaves.

But the winds of change propelled by the Second World War opened another avenue for the oppressed to explore.

Ellis writes that black heroics during that conflict were marginalised. Many returned in a state of abeyance, their future uncertain.

But the killing fields of Europe brought a sliver of hope.

Infrastructural and demographic devastation opened the flood gates of opportunities for black workers. Great Britain needed to be rebuilt.

Brixton, hollowed out by repeated bombings became Ground Zero for black immigrants. We are introduced to the Brown family, and others, and their adaptation, their experiences echoing those of countless. Families drew closer in this strange land. Women, in particular, formed an impervious bond, if only for the sake of their families. They eyed a broken education system, mindful that social mobility was the antidote to generational poverty. Pertinacity was key to surmounting the shocks of a new culture, prejudice, and xenophobia.

Ellis elaborates, "Historically, the British school system has evolved to cater for three types of pupils, those with learning disabilities, the average child, and the very able to be taught in different schools. The run-down schools operated on these principles. Their children would be viewed as 'problems' because they had come from the island ... they were black and working class and because they lived in the decaying inner cities."

NON-CONFORMIST CHURCHES

Ellis perceptively examines the role of non-conformist churches in the post-slavery era. Known for their role in fanning many uprisings on the island decades earlier, they had again sided with the marginalised. Ellis recalls, "Now, the Methodist Church was helping many childen and their parents to achieve their educational goals in Britain."

BRITISH EDUCATION

But the author's emphasis is on Britain's education system, a system that worked against the interests of black immigrant families. Essentially, she is challenging the impartiality of Britain's political party.

"The wants of middle-class parents and their children have always been a priority for all the political parties in the inner cities. Head teachers and governing bodies were reluctant to promote the young and incredibly talented black British teachers coming into inner-city schools. More liberal views and the movement towards equality proved ephemeral with the enactment of the Education Reform Act, 1988, introduced by the Conservative Government." More importantly, Ellis argues that "state secondary modern schools were created to meet the expressed demands of white working-class communities for decent school provision."

She concludes that "they were not created to deliver quality, equality, and social mobility via schooling, but to maintain the status quo and the source of manual labour for society. Grammar, public, and private schools were designated to deliver social mobility via the school system," and "it was not surprising that many pupils from Black Minority Ethnic communities continued to receive poor-quality schooling and thus failed to meet the required GCSE examinations."

She later adds, "The impact of the education system on their children would be borne out in the following decades as the mountains and mountains of research, reports, government enquirers, and targeted funding, [found] that many pupils from the islands and mainland communities were underattaining in the school system."

Still, children of the Windrush persevered and excelled. The final chapter of Ellis' treatise, ably titled Reflections, presents the many accomplishments of immigrants. And it is here that Ellis' dialectics must be examined. She pens, "Racism had not diminished, disintegrated, disappeared or died in the United Kingdom with the older generation of white working-class people ...[But] to be, fair many who worked alongside immigrants, and over time, they became good neighbours and colleagues in workplaces, supporting each other in troubled times until their retirement ... Their lives became interconnected, and they tolerated each other."

This second instalment of African Journey is defined by its rigorous historical and sociological research. There is, also, an unmistakable existentialist element to Ellis' every thought. With remarkable affect, her work transcends the black experience. And if there are any doubts, the hanging signs outside many dwellings - "No Irish, no Blacks, no dogs - " is telling. On multiple levels An African Journey is a living document on tenacity and survival.

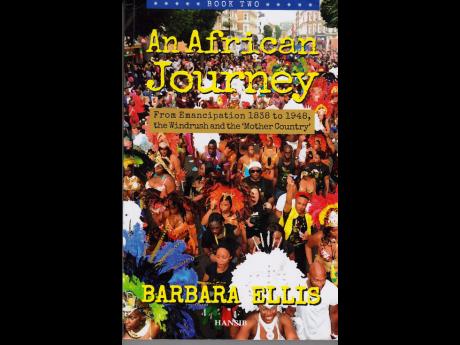

An African Journey: From Emancipation 1838 to 1948, the Windrush and the 'Mother Country' by Barbara Ellis

(c) 2018 Barbara Ellis

Publisher: Hansib Publications Limited

ISBN: 978-1-910553-91-6

Available at Amazon

Ratings: Highly recommended

Feedback: glenvilleashby