Walter Molano | Brazil: The samba revolution

There is an old saying, 'Conflict is the midwife of change', that prescribes what could be Brazil's subtle revolutionary transformation.

The past 18 months have been traumatic. The implosion of the commodity bubble, the Lava JATO scandal and the endless impeachment saga of President Dilma Rousseff dragged the economy into recession, shattered its reputation among investors and pushed millions of households back into the chains of poverty.

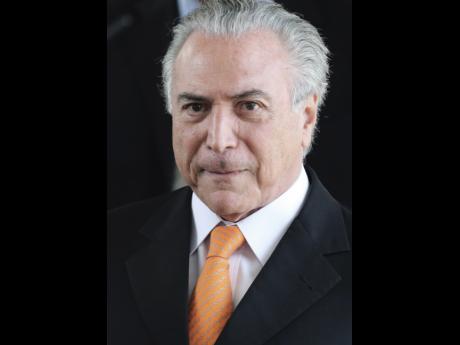

There is hope that President Michel Temer's new cabinet will stabilise the economy, restore its investment-grade rating and rehabilitate its reputation in the international community. The new administration has already taken an important step in that direction by reducing the number of ministries to 23 from 32.

Finance Minister Henrique Meirelles has vowed to slash government positions by at least 4,000 employees, the bulk of them comprised of the 24,000 members of the PT that gained employment since Lula took over. He has promised not to raise taxes or reimpose the dreaded CPMF cheque debit tax. And he is expected to de-index pension benefits, which will help reduce the fiscal deficit and stabilise the country's debt-to-GDP ratio.

Important implications

Yet, there is another change that appears subtle, but could end up having important implications.

PMDB is Brazil's largest political party, but it has not governed the country since it was founded.

Brazil has had a fragmented and torturous democratic experience since the end of the military regime in 1985. The military took over in 1964, in a coup that was largely engineered by the United States. The next year, the military rulers reorganised the political spectrum into two sanctioned parties, the ruling ARENA party and the opposition coalition called PMDB.

Although the latter eventually led the country out of military rule, its first leader, Tancredo Neves, died in 1985 before taking office. He was replaced by his Vice-President Jose Sarney, who was not from the PMBD, but led the country for the next five years.

For one reason or another, Brazil has been governed by a series of vice-presidents Jose Sarney, Itamar Franco and Michel Temer who have pushed the country in new directions. For the three decades following the end of military rule, the PMDB served more as a political machine rather than an instrument of national leadership. Its main electoral focus was on congressional and gubernatorial elections.

With the public sector representing 40 per cent of the Brazilian economy, it became a conduit for systemically tapping into the largesse of the state becoming synonymous with the country's rampant corruption. At the same time, the leadership role was relegated to the smaller parties on the right (PSDB) and on the left (PT) sides of the political spectrum.

The PMDB always shifted its allegiance to the winning side to give the ruling administration the majority it needed to govern the quasi-parliamentary legislative system, while focusing its main efforts on more nefarious activities.

Historical milestone

This is the reason why the appointment of Michel Temer as president is such a historical milestone. For the first time since the end of the military regime, the PMDB has found itself with its hands on the reins of power.

The entire nation will be watching to see whether the party, which has never had an ideological base and represents a wide political spectrum, can govern effectively and responsibly. If that is the case, we may witness a sea change in Brazilian politics. We may see the transformation of the PMDB into a party of leadership, rather than a political machine.

Although Temer is not known for his charisma or innate leadership qualities, he could set the precedent for a new PMDB. This could also trigger important changes among the smaller political parties, such as PSDB, PFL, PT and PP. It may force them to regroup or merge in order to establish the clout needed to confront a powerful adversary, such as the PMDB.

In less than five months, we will get the first taste of how the electorate will react to the new political landscape when Brazil holds municipal elections.

The real prize

However, the real prize will be in two years, when the country has its next presidential elections. The fiery end of the Rousseff administration may have not only spelt the demise of the PT, but it may have signalled a defining blow for all of the small political parties.

Out of the political crucible that engulfed Brazil for the last 18 months, we may see the emergence of a new political force that will no longer focus on systemic corruption. Instead, its new emphasis will be on economic excellence and national leadership. This has implications that transcend the nation.

A strong and competent Brazil will be a catalyst for the rest of the region that will allow the neighbouring states to orbit around a new gravitational force. Hence, like the melodic harmonies of a samba, subtle shifts in rhythm mark revolutionary changes in direction.

Dr Walter T. Molano is a managing partner and the head of research at BCP Securities LLC.