Reparation: a legal perspective (Part 2)

Historically, many civilisations in Africa practised enslavement, which took different forms in different places. Enslavement in African societies might have involved criminals, prisoners of war and debtors - and it did not necessarily involve ill-treatment, or even hard labour, but the loss of freedom.

People who were unable to feed themselves in times of famine might have voluntarily agreed to become enslaved in return for food. Their children would also have been enslaved, but both generations might be treated as part of the family. Slaves could, in some cases, rise to high positions. Sakura, one of the kings of Mali, was an ex-slave.

Slavery in Jamaica was different. Here, the slave was property condemned to hard labour under harsh conditions for the enrichment of the slave owner, without hope of reprieve; the slaves was chattel, not human beings. The inability of former chattel slaves to emancipate themselves from mental slavery is as real as a broken leg.

The descendants of former slaves take no comfort from expressions of sympathy and sorrow from those who were enriched by slave labour.

Belated declarations of regret for slavery and colonialism will not get rid of the shame and disgrace to the offender, who must be held more meaningfully accountable for the offence. Nor will such palliatives cure the mental damage of the victims. There must be some form of reparation that will ease the conscience of the offender and better the condition of the victims.

REVERSE JUSTICE

When the British government passed the Emancipation Act of 1833 for manumission of slaves, by the same act, the Jamaican planters received £6m for the loss of property in the slaves, but there was nothing for the slave.

It is universally accepted that reparation is due to the victims from those who practise illegal acts against large groups of persons as crimes against humanity by enslavement or deportation on religious, political or racial grounds.

By a perverse twist, the victims of enslavement received no compensation, but the wrongdoers were compensated. This was reverse justice for those who had lost more and suffered more during the period of their enslavement; and were made to suffer further under colonialism when discarded from the plantations to wander penniless, unskilled and dispossessed of property in a strange land, without knowing the way back home. It can never be too late to correct injustice of this magnitude.

Restorative justice may be the way forward to address the crimes committed against the black people of Africa during British colonial rule in Jamaica.

Restorative justice is a new theory of justice that requires all with a stake in the offence to redress the aftermath of the offence collectively, with a moderator, for the best interest of the community affected; in this case, Jamaica, with a moderator appointed by or from the Commonwealth of Nations. This is better by far than together building a new prison to accommodate more prisoners in comfort.

On a wider view, all offending nations of Europe could be persuaded to join restorative justice for the entire Caribbean instead of providing piecemeal benefits singularly.

From a legal perspective, restorative justice is the way forward.

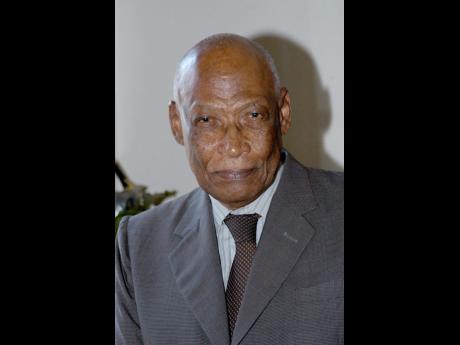

• Frank Phipps, QC, is an attorney-at-law. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com.