Louis Moyston | Jamaica: the land of wood and water?

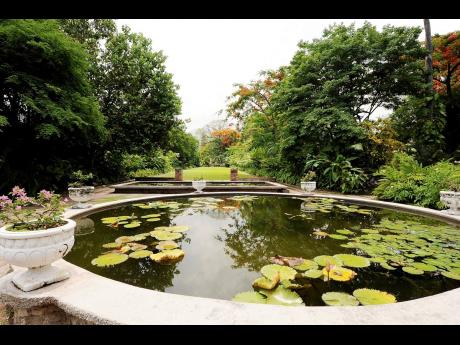

When the European explorers encountered Jamaica, they must have been struck by beauty, serenity and mellowness that forced the utterance, “the land of wood and water.” In fact, this phrase is still alive, but is Jamaica really “the land of wood and water”?

I appreciate and respect the notion of climate change, but it must not be used as scapegoat for the errors committed by those in the past, and also the continuation of those blunders by our people today. I try to imagine when Jamaica was the real land of wood and water, and then compare that thought with the present: a history of the clearing of land for sugar cane and bananas; and in these modern times, bauxite mining, mass housing schemes and overnight mega cities.

At the turn of the decade of the 1970s, the issue of the environment and major natural disasters was a major concern, especially for the underdeveloped areas – the poor countries – and, of course, the poor, the victims, were blamed.

To highlight the point, a view exist that the “four horsemen of the Apocalypse ride preferentially in the skies” of the tropics which is cursed with natural disasters; the same source informs that “nine out of ten disaster-related deaths occur among the poor in developing countries.” Drought, floods, cyclones, landslides, and earthquakes were the major destroyers in that period, and in this time it is the prevalence of fire in some areas of the developed world. The consequences of disasters imposed significant cost on the society; therefore, the matter is of supreme importance in the age of climate change narratives.

There has been the consistent abuse of agricultural and watershed lands for the achievement of short term goals in Jamaica. In the past, the coffee growers, for example, coexisted with the forest; their counterparts today, by and large, do not want to see the forest.

CONSTANT SPRING

Talk to the people in the Cedar Valley and Trinityville areas about the destruction of their roads, homes and how the structural reinforcements for the rivers throughout the communities stood up to some of the most extreme hurricanes in the past, but they could not withstand the floods of recent years.

Rivers and springs are drying up at an unprecedented rate across Jamaica; and as Peter Tosh wails out, “only the poor man feels it.”

It is not hard to visualise how Constant Spring obtained its name; and that most of the neighbourhood known as Norbrook is a watershed area. In fact, there is a place on the main road through the community where a constant spring runs from under a residence. This area has water to satisfy Kingston and St Andrew: a most adequate water supply was sacrificed by corruption and real estate greed.

Today, we are in a water crisis because of weak land regulation laws, made complicated by corrupt politicians, civil servants and rapacious real estate developers, among others. Policymakers must be careful of dealing with climate change as an expedient political issue in the face of their double standards. We must be genuine to the idea and committed to the cause and stop committing the errors of the past; but to start an action agenda for the greening of Jamaica.

We speak of the environment, plastic bags and styrofoam but we neglect the significant issue: land use and massive tree-planting activity. It appears that neither the central government nor its arm, the Forestry Department, has the imagination to make Jamaica green again.

TREE-PLANTING COMMUNITY CENTRES

Against this background, with the collaboration of the former, I suggest tree-planting community centres, led by members of their community and also the local government structure. The schools, especially those in the rural and mountainous areas, are also good sites for tree-planting centres, mobilising the people to become resilient to deal with the challenge of climate change.

In the deep-rural and wooded areas, we must strike a balance between ‘forest’ trees and crops producing an outcome of agro-forestry: the planting of food in the forest, aromatic, medicinal and exotic plants for local and export purposes. The idea can be extended to achieve further economic gains from agro-forest industry and tourism as we join the struggles for the greening of Jamaica.

The local government and some communities ought to become the “masters of the dew”; they must move to restore, where possible, reservoirs in the hills that distributed drinking water to surrounding communities in the past without the use of electricity.

Serge Island, for example, used to produce hydroelectricity for its factory and surrounding houses on the estate. Today, that dam area is called Reggae Falls. There is the need to plant trees, especially to prevent and contain general and shoreline erosion. The trees break the power of the rainfall, permitting the soil to absorb the water in a well-timed and suitable way that restores the springs and released in a judicious manner into the rivers.

I am not a natural scientist, but as an observer in the society, I see the reverse, resulting from the continued denuding of the country and outcomes of the massive flood, landslides and extreme drought.

If we are really serious about the environment, let us move from the plan to action programmes in fruit and other trees, including the bright, glowing and natural beauty of the poincianas, bougainvilleas and poui trees, for example, in all the glories of all their colours in the hills and valleys as we move in a practical manner to restore Jamaica to the land of wood and water.

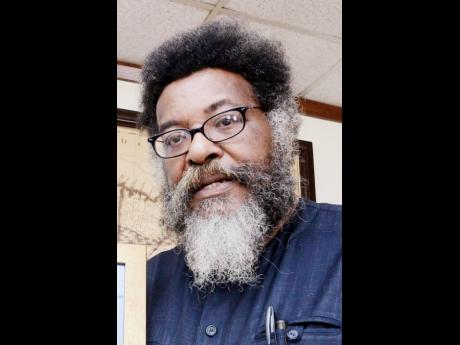

Louis E.A. Moyston, PhD. Email feedback to thearchives01@yahoo.com and columns@gleanerjm.com