Kristen Gyles | Are we really getting smarter?

In some sense, you are smarter than your great grandparents, who were smarter than their great grandparents, who were smarter than their great grandparents. This is the trend known as the Flynn Effect, first identified by James Flynn four decades ago. It is based on findings that human IQ has been on the rise since IQ testing began in the very early 1900s. James Flynn’s research showed specifically that over a span of just under 50 years, samples of Americans performed better and better on IQ tests, amounting to an average IQ increase of 13.8 points.

Each generation surpasses its predecessors in IQ test performance. Assuming that IQ tests accurately measure cognitive abilities, this means there has been a continuous growth in human intelligence. According to Flynn, if we were to evaluate people who lived a century ago against modern norms, they would have an average IQ of 70, whereas we would have an average IQ of 130 if we were evaluated against their norms.

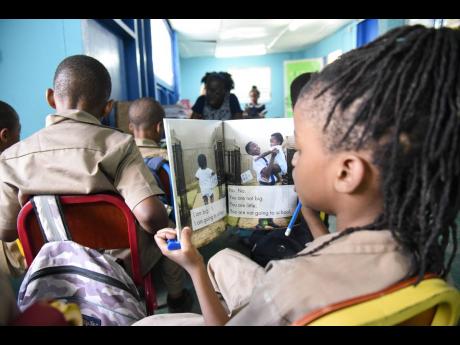

How comes? For starters, the landscape of education has changed drastically. Education is now recognised as a basic human right and is mandatory, at least at the primary level, in many countries. In contrast, not that long ago, school was a privilege enjoyed only by the elite. Furthermore, education systems around the world have matured and now benefit from improved equipment and learning aids that never existed before. Our environment is constantly changing and has become increasingly complex. As a result, our thinking has become increasingly complex.

DWELL ON HYPOTHETICALS

Moral debate has increased because we now dwell a lot more on hypotheticals. Ethical conversations abound about the rights we should but don’t have, and so do religious discussions about what to eat, wear, say and do in life and why. We engage in more abstract thinking, and logically connect ideas more.

Even at the primary level, it is now pretty typical for students to be asked questions like “If you could be an animal, what animal would you be?” or “If you could change the world, what would you do?”. We now live in a very conceptual world where we are taught to imagine all kinds of ‘what if’ scenarios that have no possibility of occurrence, but train the mind into developing scientific habits.

Our job market is also different. In 1900, only three per cent of the workforce had a job that was cognitively demanding, while in 2010, roughly 35 per cent did. Furthermore, the professions have almost all been upgraded with new, modern knowledge and a better grasp of that knowledge.

So, we are smarter, I guess. But who exactly is “we”?

Many Jamaicans were surprised by the publication of the 2022 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) study which underscored the alarming condition of Jamaica’s education system. The study, which was carried out by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), suggested the academic performance of Jamaican students was below average.

The PISA study evaluates the competencies and knowledge of 15-year-old students worldwide in mathematics, reading and science and is conducted every three years. According to the OECD, the study is intended to give “insights into how well education systems are preparing students for real life challenges and future success”. Jamaica had 3,800 students participating in the study, across 147 secondary schools.

The results revealed that our students consistently scored below the OECD average range of 472 to 485 in all the assessed categories.

JAMAICAN SITUATION

What would Flynn’s research reveal about the Jamaican situation?

The conventional, evidence-based wisdom suggests we are smarter, perhaps as a world society. But how do Jamaicans fit into the conclusions we have derived?

First, many of our students can hardly read and many of those who can read can hardly understand what they read. Numeracy skills among our students are also severely strained, such that every year we lament over the dismal pass rate for CSEC mathematics, especially.

What exactly is the problem?

While my guess is as good as any, I doubt the issue is that our students don’t have access to the information they need to excel academically. We are living in an age where information is always at our fingertips. Unfortunately, supply is high while demand is pretty low. More and more, we are demanding less information, even though we can easily access it. Could it be that we have got so used to asking Mr Google any and everything we want to know, that we are taking less time to actually learn and digest the information we assume will always be available?

Social media is often touted as a powerful learning tool that people can use to access both local and international news and that allow us to learn handy tricks and trades from each other in no time. But how much are we actually learning when we no longer have the attention span required to get through an entire five-minute tutorial video or news update? Chances are, if you’ve got this far in the article, you are a constituent of the endangered species of ‘reading humans’ who read entire articles, blog posts and book chapters in full, and not just headlines.

How can we save the dying species from extinction?

Kristen Gyles is a free-thinking public affairs opinionator. Send feedback to kristengyles@gmail.com