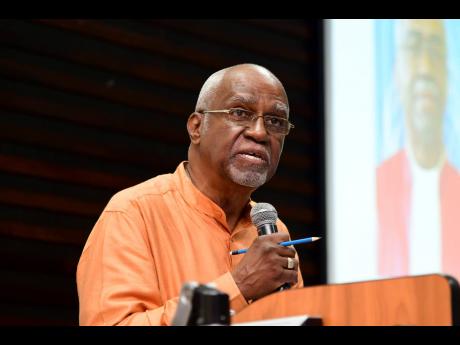

Patrick Robinson | Grange Hill Primary – preparing for 21st century realities

The Grange Hill Elementary School, which later became the Grange Hill Primary School, was established in 1924. I am a former student of the elementary school.

It appears that the change in nomenclature from elementary school to primary school took place in the latter part of the 1950s, a few years before Independence. Nonetheless, for the purpose of this presentation, the primary school as a system is treated as a modern, post-Independence institution.

As we rightly celebrate the 100th anniversary of the school, we should remind ourselves of the importance of the elementary school in colonial Jamaica. In effect, the elementary school provided the vast majority of the Jamaican population, who happened to be poor and black, with the only certain opportunity for education they would have. At Independence, after 307 years of British rule, the colonial government had only established two secondary schools, namely, Cornwall College and Beaconsfield School, now Montego Bay High School for Girls, as well as a few technical high schools. All the other secondary schools had been established by churches or by way of trusts emanating from legacies.

Thus, prior to Independence, thousands of Jamaican boys and girls had no access to secondary education, which unlike elementary education, was not free. After Independence the Government attempted to make up the deficit in secondary and other post-elementary education by establishing junior secondary and technical schools. Some of the junior secondary schools were successful, but many were secondary only in name.

Although elementary education focused on developing a certain competence in reading, writing and arithmetic, students were exposed to science and social studies, including history and geography; importantly, they were introduced to co-curricular activities such as sports, physical education, needlework and gardening.

Having transitioned to sixth class at an elementary school, some students sat the first, second and third Jamaica Local Examinations set by the Ministry of Education. Formally, education ended at 15 years of age.

Success in third year was the zenith of achievement in the elementary school system. Those who succeeded in passing third year were usually older than 15 years of age, and had some options for further educational advancement, including entering a Teacher Training College, such as The Mico or Bethlehem, or the Jamaica School of Agriculture for training as extension officers, among other things.

LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

One feature of the elementary school that cannot be overstressed is the extent of its involvement in the life of the community that it served. The elementary school was the life of the town, district or village in which it was located. Its only competitor was Church.

The elementary school, then, in colonial Jamaica was the bedrock, the foundation for social and economic mobility of the vast majority of Jamaicans.

The Grange Hill Primary School has, therefore, inherited from the Grange Hill Elementary School a rich legacy of responding to the need for young Jamaicans in Western Westmoreland, to ‘break the stranglehold of the sugar plantation culture which was so evident then’, as Dr Sylvia Palmer-Dunn put it in tributes to Rudolph Samuel Robinson on the opening and dedication of the R.S. Robinson Smart Room at The Mico University College – April 12, 2017. The Grange Hill Primary School, I would submit, has the responsibility to guard this legacy like a sacred trust.

The primary school of today has some clear advantages over the elementary school, such as the use of informational tools like computers, and teachers with university degrees. However, we continue to receive reports that the competence of our primary school students is on the decline and our children are performing at a level lower than comparable students in the Caribbean and other parts of the world. For example, according to the Patterson Commission’s Report, the 2019 Primary Exit Profile Test for Grade 6 students showed that ‘ a … third of students at the end of primary schools cannot read, 56 per cent could not write and 57 per cent could not identify information in a simple sentence’.

However, any evaluation of the primary school system, particularly the schools in Western Westmoreland, must take into account certain factors that may have affected the primary school, but did not affect the Elementary School, or if they did, not to the same degree.

The first factor is the decline in sugarcane production. In the period of the Grange Hill Elementary School, sugar was king. Sugarcane production dominated Western Westmoreland, and indeed, much of Jamaica. Sugarcane delivered to the Frome Sugar Factory in Westmoreland declined from 4.7 million tonnes in 1965 to 499,000 tonnes in 2021; sugar production plummeted from 517,000 tonnes in 1965 to 40,000 tonnes in 2021 – by any measure, these are dramatic decreases.

Sugarcane production provided employment for many in Grange Hill. I remember well watching men walking past our house carrying a machete to cut cane. Some of the cane cutters would stop at Massa Lloyd’s shop, just below our house, for refreshment on their way to work. Of course, Massa Lloyd’s bar did not serve tea or coffee. Practically everything in Grange Hill turned on sugarcane production, although there was some degree of subsistence farming.

UGLY TRUTH

The vast acreage of sugarcane surrounding Grange Hill masked an ugly truth. There was an unhealthy reliance on sugarcane production. The dominance of sugarcane production led to a syndrome of dependency in Grange Hill and other areas that resulted in squalor and poverty.

Nonetheless, in the era of the elementary school, sugarcane production provided a level of employment that is absent today because of the decline in the industry. Of course, this is not the only factor explaining reduced employment, but account must be taken of it in examining the performance of primary schools in the more modern era. Fewer jobs for parents will likely affect the attendance and conduct of their children at school. Additionally, the mind of the young Jamaican in Grange Hill today is set against cutting cane. I heard a lady from Crowda, a part of Grange Hill, insisting to an interviewer on either radio or on TV that she would not be cutting cane like her father.

The rise in crime and violence is the second factor that may have affected the primary school, but did not affect the elementary school, or if it did, then not to the same degree.

My position is not that the elementary school was a squeaky clean place of virtue. But today the name ‘Grange Hill’ is known in every corner of Jamaica. Thanks to frequent reports in the media of incidents of crime and violence in the town, all Jamaica knows not only about Grange Hill, but of some of the neighbouring areas, such as Crowda, Lincoln and King’s Valley. Indeed, we know of the trial of the King’s Valley gang conducted by the chief justice. My wish is that sometimes Grange Hill would be confused with the district of the same name in another parish.

The rise in crime and violence in Jamaica is not peculiar to Grange Hill or Western Westmoreland. Insofar as former sugar-dominated areas like Grange Hill are concerned, it is hard to deny that the decline in sugar production, and the reduction in employment have contributed to the rise in crime and violence in these areas. Grange Hill lost its economic crutch, sugarcane production, without finding a replacement. Let us be clear: the growth of tourism in the Negril area has helped the economy of Western Westmoreland, but it has not filled the void created by the dramatic decline in sugarcane production. More generally, in relation to tourism, we must avoid the effects of over-reliance and dependency that characterised sugarcane production. Glitzy coastal development must not come at the expense of inland development.

I have no empirical evidence that the rise in crime and violence in Grange Hill and the surrounding districts has had a negative effect on the Grange Hill Primary School and on other neighbouring primary schools. But it would not be surprising if it did; for example, it might have affected the attendance and conduct of students, and on a wider level, their security and that of the school. As a matter of fact, a few weeks after this celebratory event, threats of violence to parents led to the closure of the Grange Hill Primary School for a few days; more recently, a 17-year-old boy, a student of the Grange Hill Secondary School, was shot and killed while walking home from school.

My point is that any commentary on the performance of the Grange Hill Primary School in Western Westmoreland must recognise the interrelatedness of the decline in sugarcane production, the reduction in employment, the rise in crime and violence and the impact of those factors on primary schools in this area.

The damning Patterson Commission’s Report relates to primary schools as a whole. It is not an indictment of any specific primary school. As advised by the principal, the Grange Hill Primary School is performing creditably. This is very encouraging. But we cannot be complacent. We must ensure that the Grange Hill Primary School will always be a beacon of excellence in the delivery of primary education.

Judge Patrick Robinson is a former Jamaican member of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) where he served from 2015 to February 2024. This article is an abridged version of Judge Patterson’s address at the 100th Anniversary Celebration of the Grange Hill Primary School on March 6. Send feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com.