Editorial | Regulate carefully

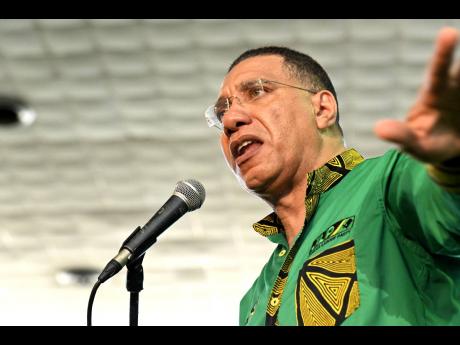

Prime Minister Andrew Holness has legitimate concerns about the growth of misinformation and so-called ‘fake news’ on social media platforms. He, however, has to be careful about which tools he employs in attempting to fix the problem.

First, the prime minister must abide by the constitutionally guaranteed principle of freedom of expression as his government navigates the tensions between upholding that freedom and protecting the right of citizens not to be harmed by the callous abuse of free speech.

This demands, among other things, an absolute commitment from Mr Holness that his bid to combat perceived harms emanating from the Internet will not lead to shadowy Big Brothers or overreaching commissariats that stifle robust debate and infringe on democracy.

He must ensure, too, that any regulatory system his government designs does not place more burden on traditional media, whose operating systems already include internal invigilation and checks and balances that severely limit the possibility of, or opportunity for, excesses of the kind that have exercised the prime minister.

At the same, Mr Holness, as leader of the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), should consider beginning this attempt at a social media reset by engaging his opposition counterpart, Mark Golding of the People’s National Party (PNP), about updating the Political Code of Conduct, which is supposed to guide the political behaviour of the island’s political parties, taking into the account the technological advances since the code was crafted a decade and a half ago.

It is not the first time that Prime Minister Holness has complained about the use of social media (which his administration once promoted as a better alternative to traditional media as a credible source of facts) to distort the achievement of his government for political ends.

But he was especially strident last week in a speech to JLP youth members. He warned that his government was considering regulations against the misuse of social media platforms, including in defaming people.

“We have been tracking, and you’re going to see some actions very shortly for those persons,” the prime minister said. “Much of what is being done is in fact against the law.”

VOLUNTARY EXERCISE

Mr Holness cited the United States and Canada as countries that “have recognised the dangers of allowing this kind of unregulated free flow of misinformation to reign”, and therefore moved to regulate the technology platforms where they find expression.

While the US Congress has indeed held hearings on the behaviour of Big Tech platforms like Facebook (Meta), Google (Alphabet) and X (formerly Twitter), there has been no specific action to regulate what these companies allow their users to do.

In fact, Section 230 of the 1996 US Communications Decency Act protects Internet service providers from the legal obligations that normally fall on publishers, once they do not themselves create the content complained against. However, the companies can, on their own volition, remove content from their networks, which essentially makes their policing of issues such as hate speech and foreign interference in US elections a voluntary exercise.

Canada has a contentious bill before the federal parliament, which, if passed, will allow regulators to demand that platforms/service providers, within 24 hours of a complaint, remove, among other things, sexual content, revenge porn-type postings, images of the sexual abuse of children, hate speech and matters promoting self-harm.

Similar regulations exist in the European Union and, since last year, Great Britain.

These issues, however, were not the burden of Mr Holness’ remarks.

REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

The focus was primarily on the false representation of his government’s policies and the defamatory statements against people, including a member of the Cabinet.

In this respect, it is noted that Jamaica’s Defamation Act gives a right of action to any person who is defamed, for which the court can award damages.

Additionally, the Cyber Crimes Act of 2015 makes it a crime (Section 9) for a person to use a computer to send another person “any data … that is obscene, constitutes a threat or is menacing in nature”. It is also illegal, under that law, to harass people via digital systems.

People have faced criminal prosecutions using this legislation.

In the circumstances, the Government should not be precipitous in introducing or expanding a regulatory framework for social media, or the Internet more generally. Any such move should be subjected to significant and clear-eyed debate, so that an action taken for the presumed good does not cause more problems than it solves.

What the Government might immediately do, however, is, for the avoidance of doubt, bring the Big Techs and their networks under the Defamation Act. This would make it clear that they are indeed publishers and therefore also liable for defamatory information published on their platforms.

Regarding the Political Code of Conduct, social media was in its embryonic state when the code was drafted. The lack of restraint in that environment, and potential to influence behaviour in a way that runs counter to the ethos of the code, should be taken into account. So, too, should the rise of artificial intelligence technologies, which can be used to distort realities and cause political and societal harm that is detrimental to democracy.