Patricia Green | Kingston developments or glorified favelas?

“…Today, close to 80 per cent of Singapore’s residents live in public housing, and about 90 per cent of the units are owned on a 99-year lease…” states the May 29 New York Times. In the 1960s, Singapore was one of the poorest nations where three out of four residents lived in ramshackle houses and were known as “squatters”. Singapore was a British colony until 1963. Jamaica gained its Independence from Britain in 1962.

Architect and Urban Planner Dr Liu Thai Ker designed for Singapore a successful social-engineering campaign, where one of his main tasks when working for the government on public housing was to ensure prices would rise slowly, enabling homeowners to feel they owned something of commercial value without the housing becoming unaffordable, published the Business Times on May 26 titled ‘The architect who made Singapore’s public housing the envy of the world’. Now 86, he is considered the architect of modern Singapore because of his role in transforming the country by overseeing the development of apartments that changed the lives of squatters. He declared Singapore’s model could be replicated in other countries.

What are the lessons to be learned from Singapore? I posit that the key is the primary concern its governmental leadership has given continuously to housing the poor. On the basis of the biblical principle in the Proverbs of Solomon, that those who take pity on the poor operate as lending to the Lord, which results in Him rewarding them, Singapore as a nation has prospered. The 2022 World Bank data shows the GDP for Singapore at 82.8, UK 46.1, and Jamaica 6.0.

DECOLONISATION ACTIVISM

I also present that Singapore’s deliberate action to house the poor was a major decolonisation activism that redressed colonial iniquity of landlessness. It thereby negated global dogma entrenched in notions of squatting and/or informal housing and settlements.

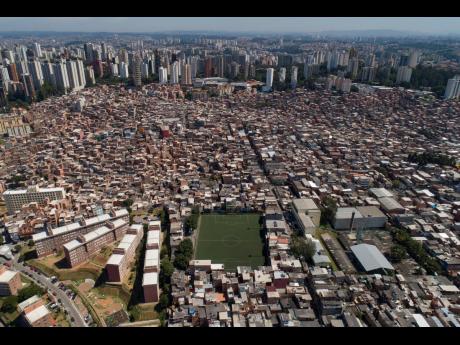

UN-Habitat defined informal settlements or slums and other poor residential neighbourhoods as existing in various forms. Interestingly, they are called squatter settlements, favelas, poblaciones, shacks, barrios, bajos, or bidonvilles. In Brazil, slums are called favelas. The Global Informality Project at the University College London stated the most important reasons for the emergence of favelas were slavery and urban migration. From mid-16th century, enslaved people in Brazil have been without accommodation and possessed limited rights. This continued for most after the 1888 slavery abolition. The 2010 census in Brazil showed about six per cent of the population living in favelas. Likewise in Jamaica, the 2011 census showed about 11 per cent as squatters.

Brazil favelas have become a tourism attraction that increased after the 2014 FIFA Football World Cup across its cities. Some of these international football patrons stayed with families inside the favelas. That year, architecture website ArchDaily published that while there are no official rules of favela construction, there is a law of mutual respect such as to avoid placing windows in a bedroom that open directly onto a neighbour’s house, or to leave a space of at least one metre (three feet) between each house.

One Brazilian tour operator, Aventuradobrasil, markets favelas globally as flourishing tourist centres, trendy with artists’ districts. To add to the fame of Brazilian favelas, one shack won the ‘house of the year’ award from an international architecture competition honoured by ArchDaily. Architects are designing slum residences, and this 2023 winning project was executed by Levante Architecture Collective who do pro bono favela house designs.

After Singapore became a sovereign state in 1965, its first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, gave Dr Liu the mandate to resettle by 1982 everyone living in slums. By 1985 slums were eliminated and virtually every Singaporean had a home. The Business Times reported in May, although 54 such apartments sold for more than US$1 million on the secondary market, families buying in the secondary market are given housing grants of roughly US$60,000. By the second half of this year, singles 35 and older will become eligible to buy a one-bedroom apartment from the government unrestricted in any location.

BENEFICIARIES

The question for Jamaica is who are, or who should be, the beneficiaries of the current trend of high-rise multi-family developments if the nation is reputed to be following the Singapore model?

The UN Sustainable Development Goal #11, “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” has Target #11.1 as “by 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums.” All nations should demonstrate that they are achieving these goals and targets, and one indicator is reduction of urban population living in slums. The Gleaner reported that the National Housing Trust had a reduction of construction activity in mid-2023 of about 61 per cent below the previous similar period, due to transferring construction to its private developers’ programme. Housing solutions completed 2022/2023 were 42 per cent fewer than the completions in the previous year. What therefore become indicators that the nation is meeting its housing targets to reduce slums in Jamaica?

The UN-Habitat three main criteria that focus on informal settlement over land, structure and services, are:

First, that slums have no secure tenure as it relates to land or dwellings ranging from squatting to informal rental housing. Singapore in the1960s contained nearly 70 per cent of the population living in slums, but slums were targeted for elimination which happened by 1985. All Singaporeans now have housing with secure tenure.

Second, that slums usually lack, or are cut off from, formal basic services and city infrastructure. Jamaica informal settlements are generally concentrated in pockets inside and around the cities, even nestled adjacent to middle and high-income residential neighbourhoods. Such settlements are without legitimate basic services. Currently, within many middle and high-income neighbourhoods, ad hoc multi-family high-rise apartment developments are now being erected but without any new infrastructure upgrading to support them.

Third, that slums may not comply with current planning and building regulations in geographically and environmentally hazardous settings, and may lack municipal permits. Jamaican citizens asking for rights to the city have been pointing out to the municipality that many of the high-rise developments are proceeding to completion non-compliant with planning regulations, some contravening legislation such as the 2018 Building Act. Others lack municipal permits and defy construction stop-orders. Yet they are completed, with some being advertised for rental on hotel booking sites.

Should housing in Jamaica redress the iniquities and inequities of landlessness associated with slums? It would seem that the flurry of new high-rise multi-family developments in established middle and high-income neighbourhoods with overlooking windows, environmental denudation, excessive lot coverage, lacking requisite approvals and/or legal conformance, some sitting on precarious slopes, may likely be described as neighbourhood ‘favelarisation.’

Patricia Green, PhD, a registered architect and conservationist, is an independent scholar and advocate for the built and natural environment. Send feedback to patgreen2008@gmail.com and columns@gleanerjm.com