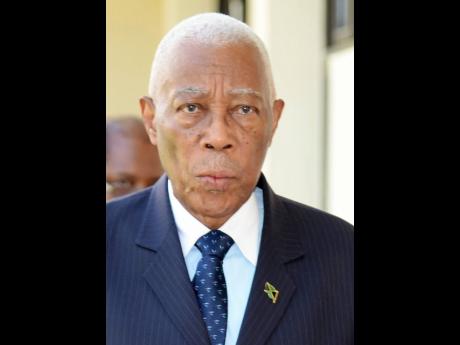

A.J. Nicholson | Strictly no referendum, find common ground

Dr Lloyd Barnett, outlining ‘Factors Guiding the Constitutional Reform Committee’s (CRC) work’, signalled: “With respect to the determination of whether the UK Privy Council should remain Jamaica’s final appellate court or be replaced by the Caribbean Court of Justice, the CRC found that no consensus existed. However, because of the importance of this issue, the committee suggested for consideration the placing of this issue as a separate question on the referendum ballot.”

Is it, then, of no moment whatsoever to the CRC membership that beginning with Canada, which completed the process in 1949 ending with St Lucia’s recent landmark step, not one of the 40-plus former British colonies across the continents that made the transition away from the UK court has done so through “the referendum ballot”?

This referendum question was, inexplicably, injected into the transition initiative by a partisan siren call from then Jamaica Labour Party leader Edward Seaga. But on what basis does a Constitutional Reform Committee put forward the suggestion that consideration of matters concerning the judicial structure be unprecedentedly placed within the hustings of an unrequired referendum exercise?

Grounded in right thinking, there are solid reasons why that road has never been travelled. What wisdom is there in holding a referendum on a matter a possible outcome of which does not lie within the power of the local authorities to implement or guarantee?

So that if the vote is for retention of appeals to the Privy Council, power or control over that outcome resides not in Kingston but in Whitehall, where the British authorities would no doubt ponder what led those Jamaicans to pose a referendum question on a matter that is ‘exclusively within our gift’.

PRUDENT REASON

That would surely have constituted a prudent reason why all territories that made the transition altogether shunned the referendum ballot, which, in any event, just as in Jamaica’s case, has never been legally required.

Moreover, several entities, including the Jamaican Bar Association and some trade union organisations, have long publicly warned of irreparable damage that could attend the vulnerable judicial structure by exposure to the dangers of the political hustings, a path which all before have feared to tread.

The question is sometimes asked: Why are you afraid to trust the people? Deeper reflection would soon reveal that this is not a matter of not trusting the people, but a matter of not trusting a referendum exercise to leave the judiciary arm of government unscathed.

It is long past time that this thoroughly negative referendum idea was excised from the transition conversation. The record shows that in the Westminster system of government, the referendum mechanism has proven to be the thorniest route in any process of change, leaving irksome consequences in its wake.

In our system of government, consensus – finding common ground – referred to in the CRC’s Report, lies at the heart of governing in the people’s best interests.

The Constitution sets out the issues that require a referendum for change to take place. For other changes, including this transition, common ground is required to be found by the authorities in the voted-for Executive and Legislative branches.

Regardless of the view taken of the reasoning of the Privy Council judges on this transition process, their declared requirement of a two-thirds majority vote in each House of Parliament sends the signal of consensus being unavoidably reached across the aisle.

NOT BEEN ADDRESSED

This important question of the imperative of finding common ground has not been addressed more clinically than by Bruce Golding over a decade ago.

In opening the debate on the Charter of Rights Bill in 2011, in which the issue inescapably arose, Prime Minister Golding nimbly alerted his colleagues in the House of Representatives, and the public, to the highly improbable path being advocated for Jamaica to take.

“What we will need to do,” he indicated, “is to see how we can reach a consensus because ... the fact of the matter is that there is no other way that it can come about.”

He explained: “Anything that is to be put to the people in a referendum to amend the Constitution starts here with a bill. That bill requires two-thirds majority (vote) before it is put to the people for a simple majority. If that bill does not get the two-thirds majority (in both Houses) and the Government, whichever is the Government of the day, decide that they are still going to put it to the people, it then requires a sixty per cent majority, something that has never been achieved in any political arrangement in Jamaica.”

“And therefore,” he stressed, “that’s how the Constitution was written. That’s how it was structured, perhaps for good reason”.

He concluded: “What the framers of the Constitution were saying is that look, there are certain changes that are so important that it is not just a matter of counting up the votes to see who has won. It is a matter of how Government and Opposition can find common ground.”

Finding common ground must be driven and conditioned, restrictively, by what is in the people’s best interests within which promptly regularising the challenges that beset the apex of our judicial structure squarely falls.

The revered Deacon Paul Bogle would have insisted on the authorities finding that common ground, enquiring of them: Why the pharaonic hard-headedness in continuing to unjustly withhold this empowering privilege from our citizens, your employers?

Respectfully, is that not what the CRC and all of us should be urging?

A.J. Nicholson is former minister of justice of Jamaica. Send feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com.