The Reel | New filmmakers shifting local film narrative

The Jamaican film industry has been experiencing a rapid ebb and flow in recent years and seems poised for a huge wave of possibilities. Today, we conclude our feature 'The Reel', which explores the industry and highlights the players and the possibilities of a bona fide film district on The Rock.

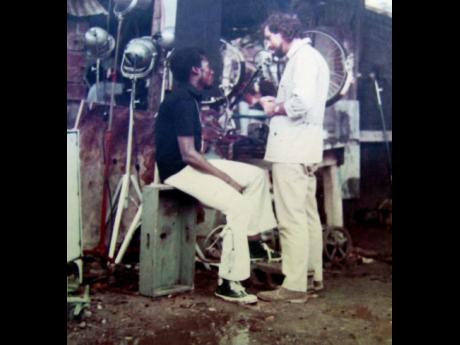

Jamaica's local film industry got a huge boost from the success of Perry Henzell's The Harder They Come. That success proved the potency of Jamaican stories on the big screen and simultaneously stunted the potential of Jamaican storytelling. That is the opinion of filmmaker Storm Saulter, who believes it is high time the shift begins, where films tell the stories of the regular man, rather than the gangster.

"Our major entrance on the scene was The Harder They Come. It was a bad-boy movie, and that has been the culture since. And with our history, our socio-economic conditions, we have a 'bad-man' culture that has been reinforced," Saulter told The Sunday Gleaner.

The filmmaker explains that the presumption of films about people of colour is that the stakes are high - that people are going to die. He believes that real, radical Jamaican cinema - the type of stories that will propel the industry forward - is less extreme. "It's not all about the roughest-ghetto-to-riches things. It's people in the grey area. It might sound boring, but those are the most radical stories to be told," he points out.

Since The Harder They Come, Dancehall Queen, Shottas, Ghett'a Life, and others, international audiences have come to anticipate action-packed turmoil. "We have to break that and show other people. It's radical but way more realistic. If you're setting out to make a film now, the last film you want to make is a crime movie. It's at saturation."

A New Narrative

This year, Saulter hit the film festival circuit with his latest feature film - Sprinter. Putting his money where his mouth is, the story sidelines the country's crime-riddled reputation, instead zooming in on the life of a high-school boy - a 'barrel pickney'

- trying to connect to his roots scattered across the world. "In the reaction from Sprinter, it's proved that people want to see something different," Saulter said.

He explains that focusing on normal anxieties would be making a bold move in the filmmarket, telling real, radical stories - for the comprehension of international audiences.

"To aspire to make movies like Hollywood, we need to find a Jamaican narrative that may not feel like an American or Eurocentric one. And I think emerging filmmakers are aware that that's where we need to go - a new narrative with an original voice."

Patois

As young filmmakers work to uncover production styles and storytelling that is distinctly Jamaican, they must also determine the film's language. "I would love to show a character being true to themselves. However, some people may not appreciate subtitles," Saulter told The Sunday Gleaner.

Those people to consider are wider than just the audience. In the international film market, subtitling films drives down the price - encouraging a blockage against foreign-language films from major distributors, who are less likely to buy in. "With some stories, you can straddle the languages ... . It all depends. Personally, creatively ... I would say, be as close as possible to the character and not straddle the language, but ultimately, it's a creative choice. If you have to use subtitles, you have to."

On his visit to Jamaica recently, Hollywood writer and director Joel Zwick confidently purported that Jamaican filmmakers must use English. "There is no reason to tell your stories in any other language than English as the English-speaking world is vast. When we write in Patois, we are locking out a host of people who want to understand," he said.

Labelling Zwick's comments as myopic and deeply colonial, State Minister in the Ministry of Culture, Gender, Entertainment and Sport Alando Terrelonge challenged the director, positing that it would be difficult for Jamaican stories to maintain their authenticity if told strictly in the 'Queen's English'.

Terrelonge highlighted the local fandom of Indian soap operas Strange Love and Made For Each Other and long-running South African drama Generations - suggesting that Jamaicans and people of other nations are comfortable with the use of subtitles and the observation of other cultures presented.

"Why would we consider to tell our stories in any other form but our native tongue? When Latin America, the Chinese, the French, and African filmmakers produce their films, they have no reservations if the world can't understand what they're saying, and then they use subtitles or voice-overs."

As the Jamaican film industry moves forward, the task for all involved is capturing authentic stories that portray Jamaica outside the realm of 'gangster land' or 'island paradise', using our mother tongue.