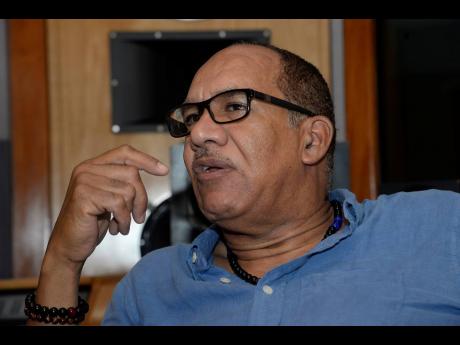

Big Yard’s Robert Livingston almost went bankrupt 5 times

Big Yard Music Group’s CEO, Robert Livingston, an artiste manager and producer whose list of accolades in the music industry is quite distinguished, has also had his (un)fair share of infamy, ironically from the same persons who he teamed up with on their spectacular journey to stardom. But, he is still grateful for the opportunities that he has had, and continues to have, to inspire artistes and channel reggae music in the global space.

“I have had the privilege of being involved in this for a minute,” he told The Gleaner. “I was 19 years old when I went on my first tour with Gregory Isaacs and Clint Eastwood. This came about because I was friends with Junior Delgado and through him, I met artistes like Dennis Brown, Gregory Isaacs and others.”

At one point in his career, he even worked with Bunny Wailer’s Solomonic Productions and subsequently with Maxi Priest. However, the curious thing about Livingston is that despite being around a horde of Rastafarian artistes throughout his lifetime, he has somehow always managed to remain a ‘baldhead’.

“Well, to be honest, I almost convinced myself to become a Rasta at one point,” he confessed, “but the problem was that I didn’t fully understand it. And I still don’t fully understand it.”

Livingston, who says that he counts his blessings, because if you don’t, “then God’s not going to give you any more,” revealed that on five separate occasions he almost went bankrupt. But those days are far behind the entrepreneurial father of nine, who jets between homes in Florida and Jamaica every two weeks. He admits that this kind of lifestyle comes with its own share of difficulties, but he is in charge, most of the times. “There are the occasions when you want a particular shoes to wear and then at the last minute, you remember that you left it in Jamaica,” he said.

Chris Martin’s Album

Among his projects out of Jamaica is Chris Martin’s latest CD, And Then, which was recorded at Big Yard, the place Martin calls his musical home. Livingstone has production credits on eight of the 15 songs on the VP Records CD and he is also named, along with VP Records boss Chris Chin, as executive producer. But while Livingston sang the praises of Chris Martin, who he pointed out “has good writing skills, great voice and personality and star quality,” he is still not totally sure what role he will eventually play in the singer’s career.

“He has a manager and I respect that. Give credit to Kingie for what he has done,” he said. “I haven’t yet cemented in my head what my contribution will be,” he said, adding that he likes the young talents in reggae and dancehall currently. He thinks, for example, that Tommy Lee is disciplined and spoke quite highly of the controversial dancehall artiste. “He uses the studio here to do his work, and one evening when I was about to leave, I saw him in the yard and went over to him and introduced myself. He couldn’t believe it,” Livingston said.

The artiste manager/producer, whose career took off in New York, has played an integral role in the success of two major Jamaican artistes – Super Cat and Shaggy. He says the difference between his journey with Shaggy and that with Super Cat is this: “I went looking for Super Cat; Shaggy came looking for me.”

He recalled that when Shaggy, who had just returned from the marines, approached him in New York, he really wasn’t interested in managing anybody because he had just had the split from Super Cat.

“Shaggy and I met and then he called me back, and I eventually agreed to do it. I told him that I wanted a 60-40 deal, because I was the one who would be making the investment.” He noted that that was a reasonable deal, because many managers at that time, were signing 50-50 deals.

After 21 years of hard work, which saw the artiste selling diamond and earning multiple international awards, the relationships ended on the same note as that of Super Cat’s. Separation.

“It hurt me to my heart to see that I build two monster acts and they don’t talk to me,” Livingston said.

“I don’t know to this day what happened,” he said of both. And while the break-ups were both painful, Livingstone still has a lot of regret as far as Shaggy’s is concerned. “That’s a family that I never wanted to lose.”

He added, “Everything that I’m doing, he’s a part of it. The studio in New York was both of us, if he’s buying a new car, he tells me. I deal with him like a son.”

Not bitter

Livingston, however, is not bitter and he pointed out that Shaggy is deserving of all the success he had made in entertainment. “He is a hard worker. Doesn’t miss a flight. Never late for a studio session.”

Super Cat for him was “a very talented, disruptive in some areas, character. We both had a lot of trial and error. Lots of different challenges. The time that he really respected me was after the split,” he said with a cynical laugh. “You can do me anything, but just don’t call me a thief. When everything went down with Super Cat and lawyers were calling me, I just gave up everything. So I never got a cent off the (1992) Don Dada album. No royalties. Nothing”

Did he learn from my mistakes? “Actually, moving forward, I made some better decisions,” he said, “but I also repeated some of the same mistakes.”

He revealed that his ability to think like a gangster has served him well in the music business. “I think like a gangster. I grew up around them. A paper overseas one carried an article that said Shaggy’s manager is a mobster. But that wasn’t true,” Livingston stated.

And despite the betrayals he has suffered, Livingston says he always tries to deal with people fairly.

“I have to live with people. I can’t act like I don’t need people. The nine furlongs is a long race,” he said philosophically.