Miss Lou ‘a good person and a skilful poet’, says Morris

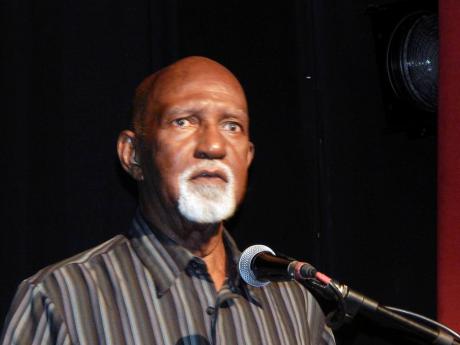

Louise Bennett was a good person and a skilful poet.” That pithy statement about Jamaica’s most loved cultural icon was made last week Tuesday by long-time Bennett researcher, University of the West Indies Professor emeritus Mervyn Morris.

The sentence came at the end of the 2019 Edward Baugh Distinguished Lecture, which was titled ‘The Cunny Louise Bennett: Values and Craft’. Delivered at the Philip Sherlock Centre for the Creative Arts, it was one of the many events focusing on Bennett during the hundred-day period of Jamaica’s celebration of her life and work. They began in the week of the 100th anniversary of her birthday, September 7.

As befitting a talk on poetry, irony abounded – on many levels. Surfacing early was the fact that from she was a child (thanks to the influence of her mother, grandmother and a great-aunt, a Marcus Garvey adherent), Bennett loved Jamaica’s native culture. However, not only was her formal education in the arts mainly European, but Jamaican culture was denigrated.

Morris quoted her as stating: “All the things in our oral tradition, handed down to us from generation to generation, were very much alive and vibrant around me. I was excited by them, though I sensed … they were not the things to which one should aspire, not the things that one should desire to learn … or indulge in. In fact, they were to be deplored, despised as coming from the offspring of slaves who were illiterate, uncultured and downright stupid. The general and accepted trend was to be as European as possible.”

Morris said that when Bennett made it clear she wanted to be a writer, her mother, a dressmaker, respected her wishes, telling her, “If you can write as well as I can make a frock, you will have a successful career.” And later she encouraged her daughter to accept the many invitations she got to perform her work, even if she was not paid.

At the same time, Morris pointed out, though Bennett was greatly concerned with her African heritage, she acknowledged and celebrated other influences. He quoted from one poem which tells of the meeting of Asian, European and African cultures which are wheeled, turned and rocked together, “an lawks de riddim sweet”. In some of her poetry and radio monologues, she references and echoes English writers – from poet Tennyson to operetta creators Gilbert and Sullivan.

Morris said that Bennett attended her first dinki mini with her grandmother, Mimi, and linked the traditional folk ceremony aimed at cheering up the grieving relatives of some deceased person to the fact that Bennett’s poems are often about confronting hardships. Bennett herself said that a favourite expression of Mimi’s was, “Tek kin teet and kibba heart bun.”

Morris told the audience that Bennett was taught to respect people and, to her, everybody was a lady – “the fish lady, the yam lady, the teacher lady”. Nevertheless, she was incensed at the man who published her first book and sued her, claiming he had the right to all her subsequent books. In anger she published a poem, Old Puss, which included the lines, “what a wutless dutty swine … dem should pass a law to hang man like dat fi tief.” Later, on reflection, she said she was ashamed that she had used her talent in anger.

According to Morris, Bennett’s poems “inhabit a continuum extending between celebration and judgement, between purposeful satire and sheer comedy.” Additionally, “Many of the poems suggest sympathy with the small man engaged in the struggle against systems he does not control.” He cited Sarah’s Choice and Census, but made the point that ultimate approval was qualified by irony.

He said, “Many of the poems expose people ashamed of being Jamaican or ashamed of being black.” Poems like White Pickney and New Governor ridicule class and colour prejudice.

Morris spent a lot of time on the poem Jamaica Ooman (referenced in the title of his talk), a work praising the achievements of Jamaican women and girls, saying that it was “a more comprehensive gender statement than appears elsewhere in her poems.”

After the lecture, a trio of musicians – Peter Ashbourne (piano), Rosina Christina Moder (recorder) and vocalist Tiffany Thompson – performed a Louise Bennett song, Evening Time. In the question-and-answer session that followed, irony again reared its head when a patron noted that though the talk was partly about Bennett’s pride in Patois, the talk and audience comments were in standard English.

A final bit of irony came during the discussion on whether Bennett should be made a national hero. Morris’ opinion was that she was already one (to many Jamaicans).

The lecturer also dealt with technical aspects of Bennett’s poetry, its rhythm and metre, the structure and flow of the stanzas, the rhyme scheme, and so on. Additionally, he spoke of her loving personality, and stressed that neither just reading nor hearing her poems would reveal all their complexities. Both were often necessary, he said.