New book depicts Una Marson as multifaceted pioneer

Part 1 of a two-part article.

A seven-year-old girl is among those currently getting acquainted with the woefully neglected but important Jamaican pioneering poet, playwright, feminist and social activist Una Marson. The girl has been reading the recently published biography written by The University of the West Indies, Mona lecturer Lisa Tomlinson.

“She finished chapter one and has been talking to me about it,” Dr Tomlinson said of the girl, a neighbour whom she had promised a copy of the book when it got published. The copy came from the University of the West Indies Press in June.

Speaking with me in her office last week, the petite, dark-skinned Tomlinson acknowledged a resemblance to the photograph of Marson on the cover of the book. She added that they were alike in other ways (their shared love for journalistic writing, for example), which may be why she has long been drawn to Marson.

Tomlinson said that Marson, her “favourite literary and cultural icon”, produced four collections of poetry and three plays between 1930 and 1945, but she was more than just a writer. She was also “a cultural activist, who worked to revive the cultural scene, not just in Jamaica, but regionally and internationally”.

RACIAL DIVIDE

By the end of her tumultuous life in May 1965, she had travelled far from the tiny district of Sharon, St Elizabeth, where she was born on February 6, 1905, the youngest of six children of the Rev Solomon Isaac Marson and Ada Marson. She and two of her sisters went on to attend Hampton School, “an elite and conservative boarding school for primarily upper-class white and light-skinned girls … known for its educational excellence”.

It was there, writes Tomlinson, that Marson developed “an awareness of race and class as she observed the racial differences and prejudice directed towards dark-skinned girls” like herself. Her light-skinned sisters, on the other hand, “were favoured by the school teachers and administration”.

Tomlinson laments the fact that “Marson’s presence in Caribbean literature is often overlooked despite her tremendous achievement in internationalising a Caribbean literary canon” through, for one, the BBC radio show she established and hosted, ‘Caribbean Voices’.

Tomlinson quotes West Indian critic Lloyd W. Brown’s statement that Marson was the “first female poet of significance to emerge in West Indian literature”. And that is only one of Marson’s many important ‘firsts’ cited in the lecturer’s handsome, easy-to-read book.

LITERARY JOURNEY

At age 20, in Kingston, she started working as assistant editor for the political journal Jamaica Critic, gaining skills which led to another ‘first’ – her becoming a co-founder, main editor and writer of the monthly magazine Cosmopolitan. The first of its kind in Jamaica, it became “a major outlet to politicise feminist views, as well as cultural and literary topics”.

In England, for five years initially (from age 27), Marson also then used her job as an unpaid assistant secretary for the League of Coloured Peoples to write about her passions in the league’s newsletter, Keys. Her pieces included articles on current global affairs and racial discrimination in England and abroad, as well as her own literary work and that of African American writers like Zora Neale Hurston and Countee Cullen.

She joined some of Britain’s many women’s organisations, which often called on her to give speeches, and Tomlinson told me she became a “powerful” public speaker.

In 1935, after landing a short-term job with the League of Nations in Geneva, she got to work with Emperor Haile Selassie in his fight against the Fascist takeover of Ethiopia. Tomlinson writes: “Influenced by Garvey, Marson’s support of African cultural expressions was intended to be a vehicle to challenge white cultural hegemony and was also to be seen as a connecting force to unite African people and to ignite African pride.”

That same year, Marson became the first black woman to go to the 12th Annual Congress of the International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship in Istanbul, Turkey. There she delivered her “most emotional speech ever”. In it, she demanded that white feminists recognise the struggle of black people across the world and, as a result, received commendation from the British press.

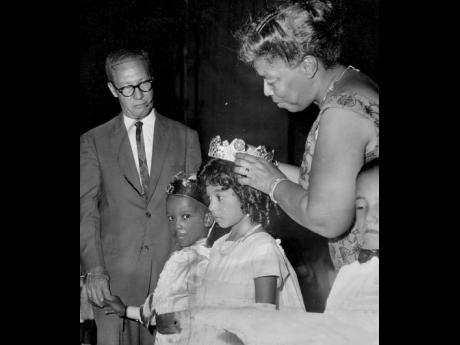

Back in Jamaica for two years, from 1936, she started a column in the newly established weekly Public Opinion, and continued to write on women’s issues and “the class system that exploited and dominated the labouring classes”. She and fellow activist Amy Bailey not only worked together “to challenge the leadership of white upper-class women”, but they started Jamaica Save the Children (JamSave) to support poor children and their families.

Part 2 next Friday.