Women and the Jamaican Political Process – Part I: The Campaign for the Right to Vote

The 20 members of Jamaica’s first Assembly which convened in 1664 were all white and male.

Jamaica was a British colony and in imperial Britain, women were completely excluded from the political process. The white, male monopoly of Jamaican politics was institutionalised by a statute enacted in 1711 which excluded Negroes and Jews from the franchise. In 1830 the Assembly passed a bill extending the franchise to free black males and to Jewish males the following year. Women were still excluded in both Britain and Jamaica.

It was during the French revolution of 1789 that women’s rights, including the extension of the suffrage to women, were first placed on the agenda of European nations. This debate led to the publication of the first book by the British writer, Mary Wollstonecraft, demanding the right for British women to vote and hold elected office in 1792.

However, over the next century, women in Britain remained subordinate to men. They were excluded from most universities, made little progress in entering professions and were not given the right to vote. This exclusion of women from politics continued for another century.

A petition by British women’s groups presented to the British Parliament with more than a quarter-million signatures calling for an expansion of women’s rights fell on deaf ears. Indeed, Queen Victoria who reigned between 1837 and 1901 described the demands by women for equal rights as “a mad, wicked folly”.

In Jamaica, both the new constitution of 1884 and the constitutional amendments of 1886 only further extended the male suffrage, giving men paying a land tax of not less than ten shillings, the right to vote.

The campaign by British women for the right to vote took on a new militancy with the founding of the Women’s Social and Political Union by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1903. Some women went on hunger strikes, while others adopted even more extreme forms of protest. Finally, In 1917 British women won the right to vote.

The following year, 1918, a campaign to extend the suffrage to Jamaican women was launched. Interestingly, this campaign was launched by two white Jamaicans of influence, H.G. de Lisser and H.A.L. Simpson.

De Lisser was then editor of The Daily Gleaner and founding president of the Jamaica Imperial Association. Simpson (1872-1937) was a colourful Jamaican legislator, who had been elected to the Legislative Council in 1911 and became mayor of Kingston that same year.

De Lisser, whose loyalty to imperial Britain was well established, welcomed the opportunity to follow the British precedent, and Simpson, ever the clever politician, was not about to miss the opportunity to add some three hundred supportive women to the electorate.

The Jamaican campaign for women suffrage was launched in May 1918 and carried extensively in the pages of The Daily Gleaner. A Woman’s Co-operative Social Club was formed to lead the campaign. At public meetings, speakers linked the extension of the female suffrage to an expansion of the welfare services offered by Jamaican elite women to the poor.

From the outset, the campaign was for a limited suffrage and the sponsors made it quite clear it was not to be extended to Jamaican working-class women.

“We do not want to have an army of women voters who will almost swamp the votes of men and who will be the type intellectually and educationally that was designated the ‘ten-shilling voter’. If that were so, a large number of intelligent women (and men) would refuse to have anything to do with politics”.

This was the outlook of the group of elite ladies who led the campaign, linked by marriage to the predominantly white planter/merchant class as well as members of the colonial administration. Their patron was the wife of the governor. Simpson tabled a bill in the Legislative Council to amend the registration of voters’ law, to extend the suffrage to women twenty-five years and over, who paid £2 a year in taxes, or earned £50 annually. Finally on May 14, 1919 the bill was taken through all stages and passed into law.

It is to be noted that the qualifications for women voters were higher than those for men. Whereas the voting age for men was 21, for women it was twenty-five. Literacy was a requirement for women but not for men, and the land tax qualification was £2 for women as opposed to ten shillings for men.

Registered women voters were a small part of the 4,359 voters on the list for the 1920 Legislative Council Elections. No women candidates were nominated and even with the introduction of women voters, the elections were low keyed, with nine of the fourteen parishes returning candidates unopposed.

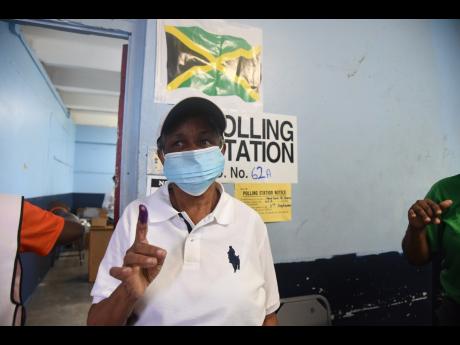

The absence of female candidates in the Legislative Council Elections of 1925, 1929 and 1935 clearly indicated that the minority of Jamaican women who were granted the right to vote in 1919 were content to limit their participation in Jamaica’s political process to voting for the candidate of their choice. It was the 1938 Labour Rebellion which created a new political environment in which mass political parties and trade unions were established. The granting of universal adult suffrage in 1944 finally opened the door for Jamaican women of all social classes to become engaged in the political process.

________________________________________________________________________________

Arnold Bertram is a historian and former minister of government. You may send comments to: redev.atb@gmail.com