Social intervention the first answer

The statistics on the current murder scene are important, especially along with other data. Even more crucial is the analysis of the stats. And an eye-opener, at least for some people, is the conclusion that follows.

The statistics, according to last Thursday's Gleaner (29/10/15), and now common knowledge, show murders up sharply in the west - Westmoreland, Hanover and St James - as well as in Clarendon, but steady or overall even marginally down in the east - Kingston, St Andrew and St Catherine North.

These data are particularly impactful when put alongside other known facts. For the west, there is the reality of lotto scamming. More significantly, there is, as well, the fact that traditional police attempts to curtail scamming, while considerable and praiseworthy, have not been matched by a comparable social intervention, which is also lacking in Clarendon (and is not a task for the police).

The social side in the west has been the welfare type, not the mainstreaming of high-risk youth that was happening in Kingston, St Andrew and that hot spot St Catherine North, where for years two notorious gangs have shot it out in the streets of Spanish Town (and are still active).

High-risk

But let me pause to list the criteria used to classify youth as 'high-risk':

* Grew up in a single-parent household.

* Dropped out of school for lack of money or impact of community violence.

* Cannot hardly read or write, add or subtract.

* Received no formal trade or skill training.

* Has family member (father, brother, uncle) involved in gang activity.

* Had a family member or friend killed in gang violence.

* Has seen guns in action or handled one himself.

* Was in lock-up or prison at least once.

Everyone will acknowledge that this is a terrifying situation for a young person. Yet it does not even catch the deep psychological trauma inflicted by the frequent experience of extreme violence to caring family and friends whom he, too, has loved. It is not a situation this youth has chosen. It is the 'upbringing' he has been given. He finds himself in this box, this deep hole, before he even knows himself.

Social Intervention

Four thousand such high-risk youth, 95 per cent male, are currently being reached by the Peace Management Initiative in nine communities of St Catherine North. The PMI has been contracted for this by the Ministry of National Security and has received the full acceptance of the superintendent of police for that division. It is such youth that the PMI and other agencies like Grace and Staff, Children First and the Violence Prevention Alliance have been dealing with for the past dozen years and more. It is why, between 2005 and 2009, there was a 40% decline in murder in four police divisions of the Kingston Metropolitan Transport Region, even while murders were rocketing up in St James, Clarendon and nationwide, and why today the levels in those four divisions remain relatively low.

The revealing conclusion, which civil-society organisations (CSOs) have long been urging but which for the first time in 50 years a Government is now accepting in a practical way, is this. There have to be social interventions of the kind that the above-named CSOs have been carrying out. They complement community policing, as well as firm policing against killers and criminals. Minister of National Security Peter Bunting has made the acknowledgement and taken some action on it.

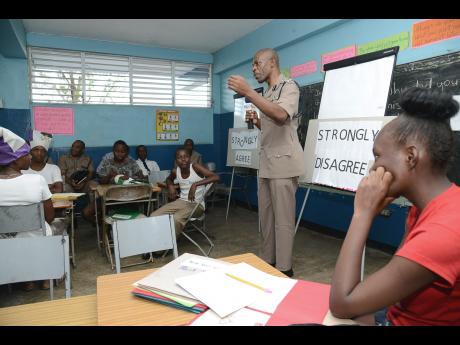

The PMI and other agencies seek to mainstream the high-risk youth by getting to know them individually, winning their trust, providing opportunities for football, for cultural activities, for training in the kind of skills that attract them like video and film-making. They also counsel the traumatised.

An out-of-city or town retreat for 50 such youth, as was done last year for 10 communities (500 high-risk youth) in Kingston and St Catherine, is also to be provided. The youth there are exposed to strict discipline, regular meals and to talks and videos on community, family life, sexuality, drugs and career paths. A file, completely confidential, is kept on each participant, and case managers follow up on every youth to ensure that agreements made in individual interviews for training or project action are observed and, where needed, help given to observe them.

Cost

What is now urgently needed is the extension of this kind of social interventions to other parishes, notably Westmoreland, St James, Hanover and Clarendon. The cost of the intervention in St Catherine, which is to run for 11 months, is a bit under $35m. The programme may have to be extended for consolidation; and a larger amount would be required for parishes like Clarendon and Westmoreland, which are geographically more extensive.

But $35m, a bit over $3m a month, is not a huge expenditure for the kind of results obtained and needed. Think of the billions spent on vehicles and other equipment for the security forces.

The minister of finance, who in 2002 as the minister of national security, made the unusual decision to have civilians deal with community violence by establishing the PMI. That decision paid off. Another decision, this time to arrange the little funding required for the expanded social programme, would be very powerful. It would reverse the decades of murder. Tens of thousands have died. Fifty years of a tragic loss of young life and talent and fifty years of victim trauma are crying out for correction.

- Horace Levy is a human-rights campaigner. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com and halpeace.levy78@gmail.com.