Miles Ogborn | Fight against chattel enslavement

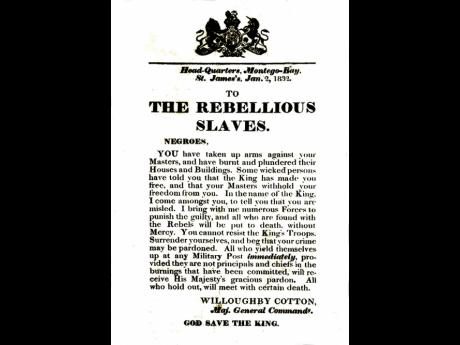

Happy New Year from the Centre for Reparation Research to all readers of our bi-weekly column. This week, we continue to mine the trial transcripts of the Emancipation War in Jamaica, which started in December 1831 and was only suppressed in January 1832, to give us a peek into the experiences of the revolutionaries who said “No!” to continued chattel enslavement.

During the early stages of the Emancipation War of 1831-2, different-sized groups of enslaved people (mostly men) sought to broaden and deepen the protest by going from property to property, raising recruits, burning pens and plantations, and fighting the militia. The largest was the Black Regiment, which fought the Western Interior Regiment at Old Montpelier Estate under ‘Colonel’ Johnson. Yet many others mobilised in more or less organised, coordinated, and well-armed bands as the war spread across the hills above Montego Bay. One such group was led by Charles McLenan of Springfield Pen. Evidence was given against him at his trial on April 12, 1832, by Henry Hine, who had been enslaved on Retirement Estate in St James

According to Hine, McLenan came to Retirement to exhort the enslaved to fight for their freedom. He told them that refusing to work [“sitting down”] was not enough and that they would not be free if they did not fight for it: “I saw Prisoner [McLenan] come to Master’s place … he said he came there for hands – he called to a man belonging to Master called Thomas Downer & he [Downer] said he could not come. Downer went as far as the Gate. Prisoner said all parcel of able hands [were] sitting down here – the Gentiles will come to these Houses and take you if you don’t go out to fight – he said the Gentiles had the Upper hand of him once, but now that he had the upper hand of them he would make them repent it (he meant by Gentiles, the White and Brown people) [. H]e said how the people here can want free if they sit down in their Houses and don’t fight for it.”

Perhaps likening himself to Moses leading the Jewish people out of slavery, McLenan gathered recruits from Retirement and Plumb estates and joined another party, led by Captain Hurlock, at Roehampton. As Hine testified, they were then ready to fight: “They then marched over to Anchovy [Estate] & when [McLenan] got there by the Wall, he asked a man & a woman there what was the reason Anchovy was not burnt down yet, if it was better than all other Estates. This was Saturday after Xmas [31st December 1831] – the party consisted of more than 50 Men – most of them had Guns – (Muskets and fowling pieces) some had Lances – when he got near to Anchovy those [that] had Guns he put before and those [that] had Lances he put behind.” Burning Anchovy elevated McLenan’s status: “he was a Captain till after he burnt Anchovy & they made him a General there … [H]e ordered Anchovy people to put the fire to Anchovy & fire was put & the estate burnt down. Prisoner then commanded the whole party [including those under Hurlock] as General.”

ATTEMPTED TO COORDINATE

After returning to Roehampton, McLenan attempted to coordinate his forces with other parties led by Captains Fowler and Williams. Hine’s evidence indicates the complexity of a fast-changing rebellion where these freedom fighters were often outgunned and needed to keep moving: “[McLenan] gave orders that night for the people to budge early in the morning to go to Breakfast at Bandon so as to go to Worcester to burn the negro Houses & also to fight the White people. [However, the] Next morning went & eat Breakfast at Bandon & were going to Worcester after Breakfast and when he got to Kempshot Penn, the Watchman told us that Fowler had gone down to Worcester with his party already & that there was no Occasion for General McLenan to go again. We remained at Kempshot till Fowler done fight the White [people] & came back to Kempshot. When Fowler came back he told McLenan that the place he stood to fight the White people the Balls were coming after him too fast & he could not stand it and was obliged to come away. Fowler then said to General McLenan he must come & let them go to Latium [Estate] tomorrow to fight the White people there & McLenan said he could not think of doing such a thing. He then returned with his party to Bandon & the next day they went to Seven Rivers & Breakfasted with Captain Martin Williams, after that Captain Williams’s party joined General McLenans & the whole Marched to Old Works (Montpelier).”

Emboldened by some success, and with McLenan heading a combined force including those already at Montpelier, “the whole marched off [in the late afternoon] with the intention of coming down to burn the Bay”, where the plantation owners and overseers had taken refuge. Yet, on their way to Montego Bay they reached a point where Captain John Tharp’s party had felled a tree to block the road on Reading Hill. There was a confrontation between McLenan and Tharpe: “Tharp asked where they were going & McLenan told him & he [Tharpe] said if any thing of the kind was to be done he was the person to do it & not McLenan to come past him & go down & burn the Bay & get the benefit – Tharpe said he was the King of this Parish. … Tharp said who made McLenan General. That he (Tharp) had Cut off two White men’s Heads at Mr Galloways Estate & he was not a General & what right had McLenan to be a General.” Tharp turned McLenan’s party back. This conflict seems to have taken the wind out of McLenan’s sails. As before, he said that if the enslaved would not fight for their freedom they would not be free, but he was now ready to give up too: “McLenan then proceeded on with his party to Roehampton, Slept there that night & went home to Springfield next day, he said every body was sitting down & would not fight for free … – he said he would fight no more[,] he would go home & sit down.”

As McLenan’s story shows, a successful paramilitary strategy relied upon cooperation and coordination between these ‘parties’. Yet their leaders’ actions and differences could also provoke conflicts over priorities, loyalty to the cause, territorial control, and status. There was certainly disagreement on the road to Montego Bay between Charles McLenan and John Tharpe over who could call themself the King of St James. In the end, the court found Charles McLenan guilty of rebellion and sentenced him to be hanged. [From TNA CO137/185/2 ff281-2]

- Miles Ogborn is professor at Queen Mary University of London. Send feedback to reparation.research@uwimona.edu.jm.