Verene Shepherd | ‘Groundings’ with Walter Rodney

On March 24 , the Walter Rodney Foundation will host the 20th Annual Walter Rodney Symposium, in Atlanta, Georgia, to mark another anniversary of the birth of Walter Rodney titled “Repairing Historical Injustices: An Amplified Call for Reparations for All Peoples of African Descent & Reparative Justice For Walter Rodney”.

This hybrid event will connect a diverse, global audience. I am honoured to have been invited to this stellar event where the keynote address will be delivered by Angela Davis, world-renowned for her activism and scholarship and for her long involvement in social-justice movements. Apart from going there to gape in wonder at Angela Davis, I will be speaking at the Symposium on a panel that will include Professor Horace Campbell of Syracuse University. There will also be the US première of the film Walter Rodney: What They Don’t Want You to Know by film-makers Arlen and Daniyel Harris. Jamaica’s own Ras Miguel “Steppa” Williams will perform at the event.

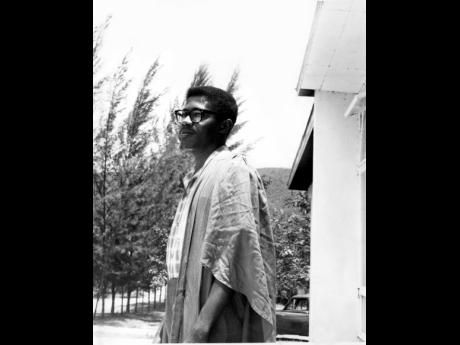

Walter Rodney was born on March 23, 1942, in Georgetown, Guyana, to a working- class family. His father, Edward, was a tailor and his mother, Pauline, a seamstress. He later married Patricia and had three children. He became a pivotal figure in 20th-century black radical politics, especially after gaining his PhD in History from The School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

He combined his historical and theoretical work with grass-roots politics wherever he lived and worked. His How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1972) is a classic study of the structure and trajectory of European colonialism on the African continent. His Groundings with My Brothers unveiled his global vision of Black Power as a unique blend of Marxism and Pan-Africanism. He taught at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania from 1966-67. Later in Jamaica, he taught African history at his alma mater, The UWI, Mona. On October 15, 1968, the Government of Jamaica declared Rodney persona non grata and banned him from ever returning to Jamaica because of his advocacy for the working poor, a ban that resulted in the “Rodney Riots” of 1968. In 1969, Rodney returned to the University of Dar es Salaam, serving as a professor of history until 1974, after which he returned to Guyana. His plan to take up a position as a professor at the University of Guyana was stymied. He then became increasingly active in politics, founding the Working People’s Alliance. In 1979, he was arrested and charged with arson after two government offices were burned. On June 13, 1980, at the age of 38, he was killed by a bomb in his car during a period of intense political activism. The Report of a Commission of Enquiry into his death has been subsequently published and efforts continue to clear his name, memorialise him in meaningful ways, and seek reparatory justice for his family.

I have always admired Walter Rodney. Regrettably, I never met him, but some years ago, I decided to pen my thoughts about him and his influence on me in the form of a letter, sections of which I reproduce here:

Dear Dr. Rodney:

I should tell you right away that I lectured in the same History Department of which you were such a distinguished member in 1968. Of course, you were in the Department for just under a year while I got a full-time post there in 1988, only leaving in 2010 as I was one of those misfits in that Department.

I have always been drawn to you, I guess because I was born with a natural affinity for people who abhor all forms of discrimination and inequality and stand up for social justice. I am still angry at how my country treated you in 1968; and even now, still feel obliged to apologize to you for such treatment.

The irony of it all is that we now celebrate our Heritage and Heroes during that very week in which the anniversary of your deportation falls, and some of our national heroes/heroine whose life we celebrate that week were black people who bawled out for justice; black power activists with an anti-imperial ideology - just like yours.

Your How Europe Underdeveloped Africa has had a profound impact on me. I read it as an undergraduate student at Mona. In this work you helped us to understand the roots of Europe’s enrichment and the negative consequences of colonialism on Africa. It was one of the most influential books in my formative academic life. Later on, I found your History of The Guyanese Working Peoples, whose basic aim was to show that working people of African and Indian descent in Guyana have a history of active struggle, which traditional history had omitted, very helpful, as I pursued research on Indians in Jamaica. You argued persuasively that every struggle plants a seed of creative disruption and aids the process that releases new social forces in the continuing drama between capital and labour.

Other aspects of your life inspire me: your refusal to imprison yourself within the walls of academia; your deep commitment to activism and public service; your sense of political mission, looking out for the interests of the working class and playing a personal role in advancing the cause of black liberation. Influenced by your wife, Patricia, you transformed from a “guerilla intellectual” to a “revolutionary intellectual”. But in your view, “to be a ‘revolutionary intellectual’ means nothing if there is no point of reference to the struggle.”

Like you, I have come to embrace the philosophy that history prepares us for activism and is a way of ordering knowledge which can be used by all as an instrument of social change. I am not alone in this. Several of us at The UWI have followed your example and embraced the role of the public intellectual. As you have stressed so often, the Caribbean was the site of the formation of European ideas of modernity and their construction of notions of hegemony, and all of us who live in Caribbean space have been deeply offended by the actualization of such notions of hegemony and feel the need to preach against it constantly. None of us can match your stature as a public intellectual, but those, like you, who have working-class origins, have shunned the path of the classic intellectual, associated traditionally with “ivory tower” and “snobbishness”, despite the persistence of this meaning of the intellectual in the popular perception. Indeed, my colleagues and I have been challenged constantly to demonstrate the relevance of history to Caribbean human-development needs as some in the society regard history as an irrelevant subject. There is an opposite view that history has an active cultural and political role because of its relationship to national and regional identity.

I will do my best to honour you on the anniversary of your birth at that stellar event in Atlanta. So as Marcia Griffith says: “Stand firm and keep the faith. Your reward should be great. We are all steppin’ out of Babylon one by one.”