Jeffrey Sommers and Patrick Bellegarde-Smith | Haiti’s disorder is the result of elite malfeasance and US meddling

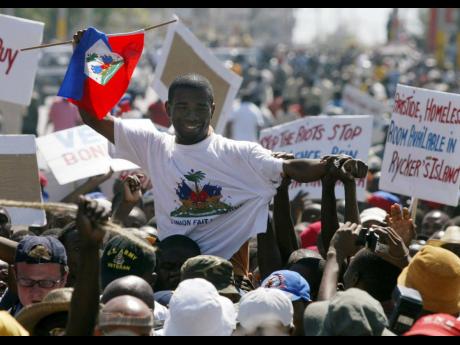

Social disorder. Prisons emptied of violent criminals by gangs looking to rebuild their ranks. Schools, hospitals, and pharmacies targeted for looting and frequently burned. Corpses left rotting in the streets for fear of succumbing to the same fate by attempts to remove them. The capital’s port was captured and ransacked, with famine threatening. Meanwhile, on Haiti’s northern coast, cruise ships still disgorge foreign tourists to the protected (with no shortage of irony) Columbus Cove Beach.

There’s no sugarcoating it — the collapse of order in Haiti and the activities by gangs in recent months to capitalise on the situation is bad.

Just as with the Middle East, we hear the refrain that Haiti “has always been like this”. Except it hasn’t. Haiti’s history has been both storied and challenged. Reasonably educated persons often juxtapose Haiti with the comparatively thriving Dominican Republic (DR), the neighbouring country with which Haiti shares an island. The comparison hints at a defect of the former relative to its better-off neighbour. Yet, a long view of Haiti reveals its current poverty relative to the neighbouring DR has been anything but constant — it only emerged in the past four decades.

No doubt a wide gap has opened up between the economic performance of Haiti and the DR. The latter’s per-capita GDP last year was roughly 700 per cent larger than Haiti’s. But, going back to 1960, the year where quality data on GDP for the two countries became available, Haiti’s per capita GDP was (inflation-adjusted) $1,716, 25 per cent more than the DR’s, then at $1,374.

Indeed, Haiti’s per capita GDP in 1960 was even a hefty 67 per cent larger than today’s rich South Korea, and far from the poorest country in the Americas. This was no one-off performance. The trend, which predated 1960, differed little up to 1980; the DR was then posting per-capita numbers 29 per cent greater than Haiti’s, which still placed them in the same ballpark.

Rather than Haiti “always” being this way, it was 1981 that marked the start of its rapid decline. The DR maintained and even slightly accelerated its steady economic growth that had until then been at rough parity with neighbouring Haiti. By contrast, Haiti’s precipitously dropped.

OIL SHOCK

Why? One reason was the 1970s oil shock, which increased the price of black gold by tenfold that decade. Needing to recycle cash from windfall sales of oil deposited with them, banks extended loans to all comers. Haiti’s dictator, Jean-Claude (‘Baby Doc’) Duvalier, gorged himself on loans, while investing too little of this cash to develop Haiti’s economy.

Meanwhile, the United States ended its inflation in 1980 with Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker’s monetary shock. This cured America’s inflation problem, but massively drove up the repayment costs of those 1970s loans around the world that had to be paid back in the now-inflated dollar.

Duvalier then made a series of lazy and disastrous bets for Haiti’s economy. He went hat in hand collecting foreign aid as cheap foreign credit evaporated, but this tranche of cash did little for Haiti’s economy. Next, he slashed taxes on export earnings and invited foreign companies to employ Haiti’s cheap labour for assembly factories. The model earned plaudits from the United States — but it did not provide much benefit to Haiti, as nearly all inputs came from abroad, tax receipts from the foreign investment were negligible, and wages were kept at subsistence levels.

Then, fearing a new swine flu, in 1986 the US Agency for International Development (USAID) instructed Duvalier to slaughter Haiti’s chief source of protein: pigs. A small, hearty variety, Haiti’s pigs were perfectly suited to low-input peasant production. USAID tried replacing them with a large US variety requiring housing conditions many peasants might envy; these new pigs died. Absent their traditional source of protein, desperate Haitian peasants turned to felling trees to sell for charcoal, thus producing the now tragically familiar images of Haiti’s deforestation.

Political upheaval followed as Haitians worked to end their 28-year-old dictatorship. The United States sought to guide this process, forcibly at points, demanding a veto power over policy in Haiti.

In 1995, US President Bill Clinton instructed Haiti to drop its tariff on US rice (subsidised and chiefly grown in Arkansas) from 50 per cent to 3 percent. Haiti’s rice production subsequently collapsed. Two decades later, Clinton apologised to Haiti for advancing this disastrous policy.

DECAMP

This coup de grâce to Haitian agriculture led peasants in the hundreds of thousands to decamp from the countryside to Port-au-Prince. Impoverished and desperate, peasants built housing from cinder blocks in the capital. When Haiti’s big 2010 earthquake hit, these cinder-block dwellings were destroyed. Official estimates put deaths at over two hundred thousand, and injuries at three hundred thousand, with another 1.3 million displaced and widespread disease following the collapse of infrastructure, from which Haiti has yet to recover.

The above is to say that it indeed has not “always been this way” in Haiti, which once economically rivalled the now-successful DR. Yet it would be too easy to blame all Haiti’s misfortunes the past half century solely on the United States — Haitian elites have made their share of errors.

On March 25, James B. Foley, the US ambassador to Haiti from 2003 to 2007, published an op-ed in the Washington Post asserting “Haiti’s dysfunction is a permanent condition” and calling for yet another military intervention. If there has been any “permanent condition” in Haiti, it has been foreign interventions, and not the despair currently being experienced in the country.

The Caribbean nations, particularly those that are members of the Commonwealth, are fiercely independent in their foreign policies vis-à-vis the United States, as many of their politicians are major intellectual figures. Their stance on Haiti comes from a position of concern; they acknowledge a shared history of resistance to imperialism. Yet, today, one still cannot discount the observation made in February 1907 by Dantès Bellegarde, arguably Haiti’s best-known diplomat and one of its most influential intellectuals of the 20th century: “The US is too close and God is too far.”

Jeffrey Sommers is a professor in the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies and Global Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. Patrick Bellegarde-Smith is professor emeritus and former chair of the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. This article first appeared in Jacobin magazine. Send feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com