How social determinants impact healthcare access

HIC shares its formula for dealing with SDOH to improve cardiovascular care

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS of health (SDOH) contribute significantly to the severe morbidity and mortality that various cardiovascular diseases inflict on the society. The components of SDOH include wealth, income, employment status, education, housing, access to nutrition, and access to medical care including mental health services.

Leveraging reliable SDOH data is critical to addressing healthcare needs of the community. At-risk populations must be connected to the appropriate resources needed to overcome these barriers to access to achieve better health outcomes.

The Heart Institute of the Caribbean (HIC) was founded in 2005 to improve access to quality medical and cardiovascular services by everyone, regardless of their socio-economic status.

HIC has encountered and learned to navigate a myriad of structural, institutional, socio-economic, cultural, and behavioural barrier to appropriate CVD care for vulnerable populations in Jamaica and the wider Caribbean.

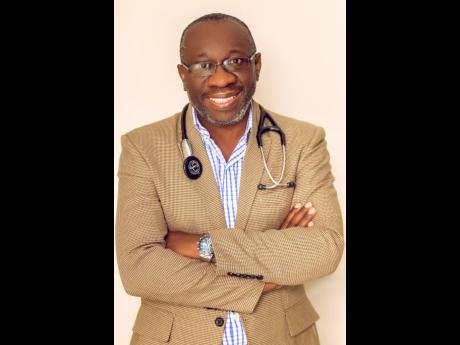

According to Dr Ernest Madu, the founder and consultant cardiologist at HIC, addressing SDOH directly will need a multipronged, long-term strategy. It will involve engagement of all stakeholders, public–private partnerships and multilateral agencies with defined targets that will aim at reducing health inequalities in various facets of the society and the economy.

“Interventions should include a combination of programmes both at the population level to shift the distribution of cardiovascular risk and also at the individual level focusing on high-risk members of society. Interventions should include civic and political engagement, and vectors of change should include schools, places of worship, government agencies, sociocultural groups, government policy, non-governmental organisations, and other stakeholders,” Madu outlined.

One important agent that can be employed is technology, he suggested. Mobile technology, particularly, has the potential to revolutionise access to care and improvement in other SDOH, especially in its ability to create information parity among the population.

“Mobile health technology can be used to reduce disparities in cardiovascular disease outcomes by overcoming such barriers as limited access to providers, difficulty communicating with providers, and inadequate communication between patients and providers regarding symptoms,” the HIC founder explained.

“For example, HIC has leveraged telemedicine extensively in the organisation by employing a robust telemedicine platform (in partnership with Netmedical New Mexico, USA) that connects patients in rural locations in Jamaica and other Caribbean islands via video to specialists at HIC and improves access to skill and expertise which ultimately benefits the population,” he added.

However, a common hindrance to effective solutions is short political cycles. “Most interventions will need governmental support or oversight and the short political cycle hinders long-term planning to address these SDOH [factors]. Funding from government agencies and philanthropists for the interventions has dropped significantly with the advent of the coronavirus pandemic,” he said.

In a recent presentation at Yale University, on the ‘Global Burden of Cardiovascular Disease’, Madu indicated that the cost of high-quality cardiovascular care in a low-resource country is daunting.

“The Jamaican population is largely uninsured/underinsured with only approximately 15 per cent of the population having health insurance. Individuals mostly finance their healthcare needs out of pocket and this is a huge burden to most patients,” he explained.

Further compounding access is the unfortunate situation where those with health insurance have very poor coverage for advanced diagnostics and treatment and in many cases, there is significant delay in response from the payers, resulting in delayed access to treatment.

“When patients present with heart attack, time is critical as the best practice standard is to open the blockage within 90 minutes of arrival at the hospital. When a payer requires five business days to issue a preauthorisation for the service, this is an impediment to access even for the insured person.

“In many instances, insurance companies may require patients to pay upfront and reclaim. This requirement effectively excludes thousands of poor patients, retirees and government sector employees with insurance from accessing lifesaving care because of their inability to front the cost of care,” Madu pointed out.

A cross-subsidy model is utilised at HIC to provide universal access to its services by patients, irrespective of socio-economic status. This model is executed through a differential pricing model where a standard rate is offered to patients who have health insurance or a third-party guarantor (such as a corporate sponsor), and a markedly subsidised rate is offered to indigent patients or those who are paying solely out of pocket or are indigent.

“This subsidy is funded through grants from HIC Foundation to ensure that good quality healthcare is inclusive and to bridge the equity and access gap in Jamaica. In addition, HIC Foundation provides financial support for many Jamaicans that have contributed to national growth but are now in advanced age and with limited income. These individuals are covered under the ‘Legends Program’ and receive free lifetime healthcare at the Heart Institute funded by HIC through its HIC Foundation,” Madu said.

The successes attained and the lessons learned by HIC can be replicated in other nations to address social determinants that impede access to cardiovascular care and medical care in vulnerable populations. It has the potential to alleviate the access gap to high-quality care in developing countries and in underserved and marginalised communities in developed countries.

Cardiovascular disease, mainly heart attacks and strokes, accounts for most non-communicable disease (NCD) deaths with approximately 17.9 million deaths yearly. An estimated 15 million people die from a NCD between the ages of 30 and 69 years; over 85 percent of these ‘premature’ deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.

Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of death, hospitalisation and disability in the West Indies. Jamaica is one of the largest Caribbean islands, with a population of almost three million people, but lacked adequate number of healthcare professionals, with 3000 doctors available. In response, HIC was established to address the dearth of high-quality cardiovascular care on the island.

The HIC Heart Hospital in Kingston is the only dedicated full-service tertiary cardiac centre in the English-speaking Caribbean that provides full out-patient and in-patient services, including complex cardiac surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, peripheral interventions, electrophysiology procedures and nuclear imaging under one roof.

The Kingston facility features an ultra-modern operating theatre suite, two interventional cardiology suites, a cardiac emergency room, an 11-bed cardiac ICU, and a telemetry unit, with an emergency cardiac ambulance service available 24 hours per day.

There are additional clinics and satellite locations in other towns on the island (Mandeville, established in 2007, Ocho Rios in 2010, Spanish Town in 2015 and Montego Bay (with an additional Interventional Cardiology suite) in 2020) which provide outpatient care and diagnostics.