Table over tablets - COVID-19 exposes inequality in society as job losses push families to the brink, says Gayle

As The Gleaner drove through Trench Town and Majesty Gardens in Kingston on Monday morning, the streets were teeming with children playing and loitering, unperturbed about lessons they are missing as classes progress online.

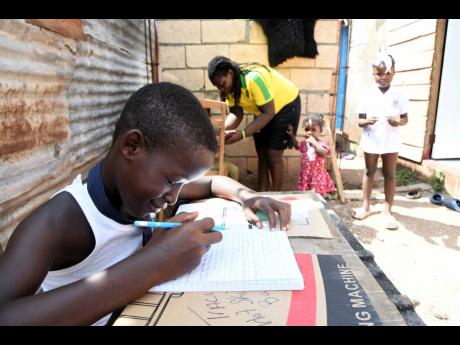

In an environment where parents have to make unenviable choices due to crippling financial constraints, the pangs of hunger win out in the immediate present over other needs, such as resources to keep abreast with COVID-era lessons – an expense many parents simply cannot manage.

A number of them told The Gleaner that they have had to forego purchasing school supplies, as they have lost their jobs due to the pandemic. When they had previously faced such dire challenges in the past, they could still send children off in the mornings without even a meal at times, relying on schools to feed them. That option is not available now, with classes being forced online to prevent the spread of COVID-19, and their children are being left behind.

A recent Inter-American Development Bank survey revealed that nearly 60 per cent of families earning less than minimum wage reported a job loss in the household, while 25 per cent high-income families reported job loss in their households. The effects are poles apart for both groups.

Kaysha Lindo, a mother of seven, told The Gleaner that since getting laid off from the wholesale she worked at eight months ago, she has been struggling to meet the basic needs of her children. While using her neighbour’s Wi-Fi, she passes around her phone among five of her kids for them to log on to classes.

She is most worried about her 15-year-old son.

“[He is] on the corner right now. Every minute him outside with other boys. It’s really bad. It’s a different influence from being in the bookwork.” 36-year-old Lindo, a resident of Second Street in Trench Town, said. “You never can tell. Other boys out there who are doing wrong. He will be on a corner with them and not being able to do his work, it will be bad; it will lead to something else.”

Social anthropologist Dr Herbert Gayle, a lecturer in the Department of Sociology, Psychology and Social Work at The University of the West Indies, Mona, told The Gleaner that COVID-19 has highlighted the level of inequality within the Jamaican society. Persons in low-income, inner-city households faced much greater hurdles and lack of opportunity, he said.

“In order to exist, you have to have both the agency ... [and] the material to survive,” he said.

Gayle pointed out that there were four basic things needed for children to succeed in the 21st century – food, a safe community, at least one stable parent, and educational training. It is an uphill task for poor parents to meet these four bars of anthropological security.”

Majesty Gardens resident Garfield Gitezene lamented a culture where young boys found joy in dressing up in masks and brandishing toy guns they had made from discarded roll-on bottles to have ‘shoot-outs’ in the streets.

Having grown up in the community, the 34-year-old shared that many children have grown to become gang members, but a change in the children’s environment would help to steer them in the right direction.

“In dem environment yah, you see mostly gun straight through the day and the night, and you don’t want the youth dem fi come see dem them things there, so you would a wish for a better community and a better approach for the youth dem,” said the father of two.

In 2017, a study led by Violence Prevention Alliance head Dr Elizabeth Ward found that “youth pointed to ‘idle hands’ and lack of youth engagement as a push factor for violence and crime”.