What went wrong at Moneague?

Two breaths of hydrogen sulphide could have knocked victims dead, says expert

As several probes continue into the deaths of three cesspool workers who inhaled noxious fumes at Moneague College on September 6, there is growing evidence of a culture of non-compliance with safety protocols among workers and bosses at Central...

As several probes continue into the deaths of three cesspool workers who inhaled noxious fumes at Moneague College on September 6, there is growing evidence of a culture of non-compliance with safety protocols among workers and bosses at Central Cesspool Limited.

While Audley Dinnall, owner and director of Central Cesspool Limited, revealed that his company provided employees with glasses, goggles and chest waders, he painted an image of a workforce that often went rogue but were not held to standards by his own management.

“When they go in on particular jobs, they have that [equipment] when they expect that they are going to use it. Not all the time it is necessary for them to have it. Sometimes they use it at their own discretion,” Dinnal told The Gleaner in an interview.

“Sometimes you have to push workers to wear their steel-pointed shoes, and if you are not there to push them to wear it, they come in slippers same way … . It is a part of the culture.”

But Dinnall will have weightier questions to answer about other safety standards that may have been ignored in the debacle in which high concentrations of toxic gases, including hydrogen sulphide, appeared to have caused Kirk Kerr, Joslyn Henry, and Beresford Gordon to suffocate.

The lines of enquiry will include whether Central Cesspool used a specialised gas meter to ascertain the gas concentration in the eventual death chamber and whether the workers were fitted with oxygenated breathing apparatuses.

Dinnall declined to comment when asked if his company possessed equipment to pump oxygen into the septic tank. He said that the Moneague incident was the first such tragedy in the company’s more than 20 years of operation.

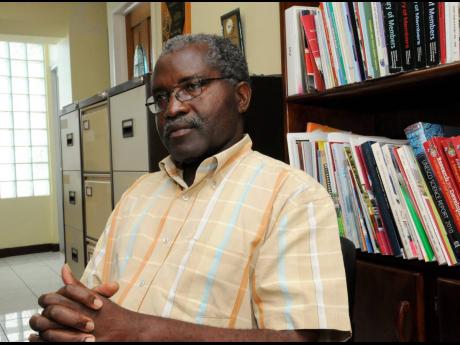

Professor of supramolecular chemistry, Ishenkumba Kahwa, believes that hydrogen sulphide was the most likely cause of the deaths.

Small concentrations of the gas at 0.01-1.5 parts per million (ppm) smell like rotten eggs but will become toxic at levels of 1,000ppm.

“If someone goes into a pit that has a lot of hydrogen sulphide in it, they would only need to take two breaths before they are knocked out and dead … . The fact that the people were rapidly knocked unconscious, it means that it would be way above 700 parts per million,” Kahwa told The Gleaner.

The professor said that no one should have descended into the tank before lowering a gas probe to establish the concentration levels. He also stressed the importance of allowing gases to disperse before any work commences – either by leaving the tank open or by lowering a duct that is attached to a pump that sucks air from the septic tank.

The United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommended exposure limit for hydrogen sulphide is 10ppm for no more than 10 minutes at a time.

NIOSH outlines that a threshold of 100ppm is immediately dangerous to life and health and might interfere with the ability to escape if difficulty arises.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has set a general industry ceiling limit of 20ppm, while the general industry peak is 50ppm.

Owner and operator of Hibiscus Guest House and Cesspool Specialist, Joseph Parker, believes that too little time may have elapsed before they entered the pit.

The deaths of the three men have come as a blow to Parker, as he has worked with the father of Beresford Gordon for more than 20 years.

James Gordon said that he has been devastated by the death of his son, who had flickers of interest in following in his dad’s footsteps from age 12.

During their last conversation in August, Beresford spoke at length about his passion for the job, said the elder Gordon.

“He said he loved the work and I tell him, yes, you must keep it,” James said.