Shalman Scott bemoans decline in Jamaica’s economic growth

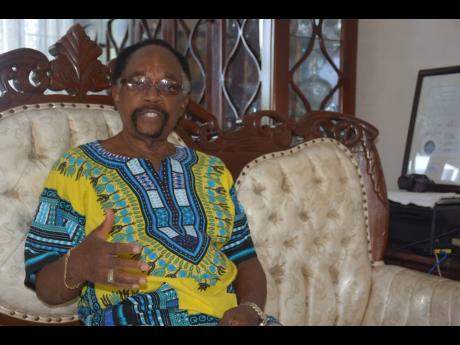

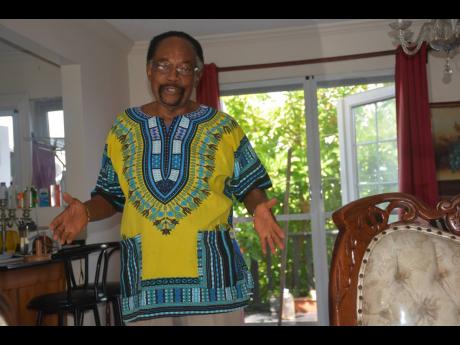

Born in 1948, Shalman Scott, one of the most prominent mayors to lead the St James Municipal Corporation and the city of Montego Bay, had the privilege of experiencing Jamaica’s Independence in 1962.

Not known to hold back his opinions on matters affecting the country, Scott has been very vocal about Jamaica’s trajectory over the last 60 years since the island got its political Independence.

“Independence was an aspiration that especially countries coming out of colonialism and slavery welcomed and aspired towards,” said the 74-year-old Montegonian, who was conferred with the Order of Distinction for his outstanding contribution to nation-building.

“And so it was a general desire for countries, as we say in Jamaica, ‘for every tub to sit on its own bottom’. That basic principle was what drove the spirit of the desire for political independence and for the Jamaican people to have a greater say in the charting of the economic and social course for the country, especially in light of what happened in the past, when there was a time when it was only the plantocracy that controlled government.”

Scott explained that becoming independent changed all of that and broadened the system of democracy which began in 1944, when the first election under Universal Adult Suffrage was held, giving ordinary Jamaicans a chance to decide on their elected representatives.

“It is very significant to understand the areas of progress that have been made over the years, but it is also pivotal to understand what preceded these areas,” he told The Sunday Gleaner.

Giving four examples, he named the Common Entrance Examination, which began in 1957, some 119 years after the abolition of slavery; the Holidays with Pay Act of 1964, one hundred and twenty-six years after slavery; the National Insurance Programme of 1968; and the National Housing Trust (NHT) Act of 1976, one hundred and thirty-eight years after slavery was abolished.

“Education became accessible to children of former slaves; Jamaicans were able to get vacation and sick leave with pay; poor houses (infirmaries) weren’t as crowded, as the NIS (National Insurance Scheme) kicked in and the island’s people could own their own homes under the NHT,” he stated.

“But, as the economy grew, those who were the ‘haves’ reaped off and creamed off the greatest part of the economy, much to the dismay and difficulty of the large masses of people.”

The increasing inequity, he said, gave rise to people turning to crime and corruption, as well as an escalation in the drug trade and other forms of criminal activities, as a way of surviving because the economic structure did not provide enough opportunities for people who became more sensitive to their right to a good life in the country, “and so all sorts of underground activity were now being pursued for survival”.

“One cannot even get a good reading where the macroeconomic performance elements are going now because that very underground economy is very difficult to read while its activities impact and converge on the formal economy,” he noted.

ORGANISED WEALTH, ORGANISED POVERTY

Using a dichotomy as an example, Scott said, if wealth is organised, poverty is also organised.

“Wealth is organised into our society, just as poverty is organised. It is not by accident that so many people have remained poor. It has always been a part of the system. One of the great signals for the insensitivity of those in political power is what happened at a time when elementary education was to be given to the children of the masses, seven years after Emancipation, and even despite the fact that England was prepared to give half of the cost, it was voted down,” Scott said.

“And that attitude has prevailed over time and has worsened because, in the last five or six decades, the economy has taken a downward turn in many areas and, even while there is talk about how employment is growing, that is not about employment. It is a question about what you are earning and, even more importantly, your purchasing power.”

Money is of no value, he said, unless it is backed by goods and services, “and so when inflation begins to reduce the purchasing power of people’s money, because of dislocation in the economy, whatever the factors, they are going to be worse off”.

Regarded as a firebrand who has served his country in several areas of public service, including as a trade unionist, Shalman Scott has been the voice of reason for researchers, talk-show hosts, politicians, media houses and the ordinary man.

He has constantly called for the balancing of the economic scale, allowing the marginalised to have opportunities.

“We made significant strides in the ‘50s and the ‘60s. When we look at the history of the Jamaican economy in the post-colonial period, we made strides in many ways. There was tremendous economic expansion and consolidation although there was inequity in the system,” he said.

But things started going downhill from there, which led to a psychological effect of mistrust, a historical and endemic mistrust of the masses of the people towards those who control wealth and power.

That mistrust, unfortunately, was bolstered by a turn in the ‘70s, and right up to where the country is now, turned against the growth that Jamaica was seeing, such as the rising changes in political ideology.

“For example, when the concept of democratic socialism was announced in the ‘70s, the [United States’] Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had its pointman down, attempting to stultify Michael Manley’s socialist programmes, which were leaning towards a greater advancement and consolidation of opportunities for the poor. It was destroyed by way of violence and destabilisation,” said the historian.

“What it tells us is that the process of destabilisation of the Jamaican economy prevented a lot of the fruit trees to bear for the benefit of the masses of our people. And so what we have had entrenched in the country, based on the evolution of our history and despite the efforts to bring progress, is this concept of organised wealth and organised poverty.”

Scott said Jamaica is still saddled with those types of issues that are keeping people back.

“Sixty years later, several decades after the period of economic growth in the ‘50s and ‘60s, after that, it has been periods of economic decline, arising from all sorts of factors but at the least of which has been the deliberate destruction of the Jamaican economy – evidence which is given by no less a person than the former hemispheric head of the CIA, Philip Agee,” Scott declared.

DORRETTE WAS HIS WORLD

Despite the heartbreak of watching his beloved country go backward instead of forward over the years, undoing the strides that were being made, Shalman Scott remains in the fight for better.

Jamaica will always be home. And he reflects on those years and events that gave rise to the man he has become.

His late wife Dorrette was his entire world, he said, the pain still lingers even after losing her 20 years ago.

Scott shared the same bench with Dorrette at Mount Zion Primary School in Rose Hall, St James, moving from one class after the other.

Best friends from as early as age seven, the two would separate when Dorrette moved on to another school. But, by the time they became college students, they reunited, both becoming teachers, making significant contributions to education in Jamaica.

Scott did not attend one of the traditional high schools in the Second City and, when he left primary school, he went to trade school where he learned electrical installation and automotive electrical, honing those skills later as part of an apprenticeship programme in the Public Works Department.

Scott went on to tutor at Cornwall College in the history department, while Dorrette later became principal of the largest early-childhood institution in the Caribbean, the Montego Bay Infant School.

As skilful as he was in electrical science, Scott was born for the classroom, and that’s where he influenced the likes of two former mayors, Noel Donaldson Jr and Hugh Solomon, who were students of his history class at Cornwall College.

It was during his tenure at the popular Montego Bay boys’ school, where he made an indelible contribution, that the people in the Rose Hall Division of St James convinced the man born and bred in Barrett Town to represent them at the local government level.

A son of the soil, it was an easier feat for him to win the seat. He did this three times, representing his community as a parish councillor for 14 years, five and a half in the position of Montego Bay mayor between 1981 and 1986.

It was he who stood next to Governor General Sir Florizel Glasspole when he announced the Act of Declaration officially awarding Montego Bay city status, on May 1, 1981, months after this was passed in Parliament in 1980.

The father of four – three boys and a girl, one now deceased – would go on to lose his wife and best friend Dorrette years later.

He has made his presence felt as an honours graduate of both Georgetown University and the London School of Economics.

He attended both institutions on scholarships, topping all his classes on completion.

Among the greatest achievements of the Mico Teachers’ College graduate today is the critical role played by the St James Parish Council in the development of the Montego Bay waterfront programme while he was chairman.

“It is those developments that gave Montego Bay the kind of status and economic standing that she now has within the context of the country’s economy. At the cultural level, the Sam Sharpe monument in Sam Sharpe Square was unveiled,” Scott said.

While he was mayor, Scott became such an integral part of the World Conference of Mayors that he was re-elected five times as a vice-president, with responsibility for the activities and programmes in the Caribbean and Central America.