Scotland: Reparation not on Commonwealth’s agenda

Campaigners want bloc to take up thorny issue in fight for justice

Shock has met revelations that reparation for slavery is not an agenda item for the Commonwealth, whose ceremonial head is the British monarch and whose members, including Jamaica, are mostly former colonies. “There has been no specific call for...

Shock has met revelations that reparation for slavery is not an agenda item for the Commonwealth, whose ceremonial head is the British monarch and whose members, including Jamaica, are mostly former colonies.

“There has been no specific call for the Commonwealth to be the platform,” Commonwealth Secretary General Baroness Patricia Scotland said in an interview with The Sunday Gleaner last week.

Member states, she reminded, are sovereign and “nobody can force them to put things on the agenda if they don’t wish it”.

That situation should change, argued professors Verene Shepherd and Rupert Lewis, two major voices in the push for reparation from European countries that profited from the transatlantic slave trade and slave plantations in the Caribbean.

“If it is true that reparation is not on the agenda of the Commonwealth meetings, then that is shocking to me,” said Shepherd, who chairs the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

“The Commonwealth has a huge role to play in the reparation campaign. After all, the CARICOM reparation movement is largely directed at the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the vast majority of the member countries of the Commonwealth are former colonised territories of the British empire whose wealth was extracted to put the ‘Great’ before ‘Britain’,” she said.

In the brief interview, the Commonwealth secretary general said that the organisation, which evolved out of the British empire, is not bounded by treaty but by “goodwill”, and it is up to member states to decide whether “this is now a time when the Commonwealth wishes to put it on its agenda for discussion”.

But she acknowledged that the group “could be a suitable platform for that debate”, pointing to the positions on issues such as climate change and even the advocacy against apartheid in South Africa.

“I think it’s very interesting, indeed, how this debate is coming more and more to the fore. And the secretariat, of course, has always been there ready, willing and able to support our member states to facilitate debate on any issue which is of keen interest to our members,” she said.

Scotland spoke to this newspaper last Thursday, following the conclusion of the Commonwealth Women’s Affairs Ministers Meeting in the Bahamas.

Her disclosure comes amid discussions over the recent publication of a report which said the United Kingdom, a key target of the reparation movement, should pay US$24 trillion to 14 countries for its involvement in the transatlantic chattel slavery. It said Jamaica is owed some US$9.5 trillion.

The total sum of reparations to be paid by all former slave-holding states is US$131 trillion, according to the calculations done by a group of US economists from The Brattle Group for a partnership involving the American Society of International Law and The University of the West Indies.

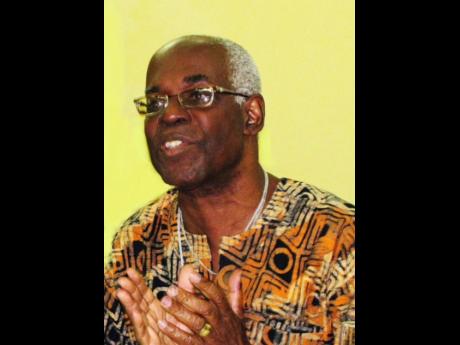

Jamaican Patrick Robinson, who is a judge of the United Nations’ court, the International Court of Justice, who wrote the introduction to the paper, said the UK will no longer be able to ignore the growing calls for reparation for transatlantic slavery.

“They cannot continue to ignore the greatest atrocity, signifying man’s inhumanity to man. They cannot continue to ignore it. Reparations have been paid for other wrongs and, obviously, far more quickly, far more speedily than reparations for what I consider the greatest atrocity and crime in the history of mankind: transatlantic chattel slavery,” he told the United Kingdom-based Guardian newspaper.

NO APOLOGY

The British government has never apologised for slavery, despite playing a major role in it.

In 2015, then-Prime Minister David Cameron, speaking from the floor of the Jamaican Parliament, told the country to “move on from this painful legacy”.

More recently, in April, current leader Rishi Sunak said “no” after an opposition MP asked whether he would make a “full and meaningful apology” and “commit to reparatory justice”.

“Trying to unpick our history is not the right way forward,” he said.

But Judge Robinson said that stance will have to change soon.

“I believe that the United Kingdom will not be able to resist this movement towards the payment of reparations: it is required by history and it is required by law.”

The Dominica-born Scotland did not answer directly whether she agreed with Robinson’s position, although she acknowledged that reparation is among some “quite challenging conversations” being “anxiously and intensely” debated “within our Commonwealth family”.

Shepherd said that while reparation may not be on the Commonwealth’s formal agenda, members, through their different groups such as CARICOM, have been lobbying for reparation.

But getting it on the agenda is crucial, she argued.

“The Commonwealth secretary general is correct that the Commonwealth could – I would say should – be a platform for advocacy for reparation. The culprit nation is the head of the Commonwealth, so why not lobby the head directly?” the historian said.

Some member states may not want to alienate financial support that comes through the Commonwealth and from the big funders, which include the UK, one Commonwealth insider said, noting that the situation could also become “awkward” for The King.

Some of the other major donors are Australia, Canada and New Zealand – a group of mainly so-called settler colonies whose experience of enslavement and colonialism historians say was markedly different from the extractive nature that characterised many ex-colonies in the Caribbean and Africa.

TIME HAS COME

Lewis, a retired professor at The University of the West Indies, said the Commonwealth is important to the reparation cause because the organisation is “the instrument that Britain has used to promote its interest in the world” and that the time has come to add “an overarching neglected issue of reparative justice to the Commonwealth’s agenda.

“Since Britain is pushing her interest in the Commonwealth, we the CARICOM countries, African countries and whoever else can be brought in to support, have to define what is our interest when it comes to this important issue of reparation which has now been quantified,” he argued.

Lewis said that CARICOM states and the Commonwealth secretary general can draw inspiration from the strong stance against apartheid in the 1970s and 1980s led by then Secretary General Sir Shridath ‘Sonny’ Ramphal, who held the position from 1975 to 1990.

“The head of the Commonwealth in the Ramphal-African-liberation-anti-apartheid days took an independent position. That is to say, it was not the position of either The Queen nor Prime Minister [Margaret] Thatcher … . Those, I think, are moral and political choices that the head of the Commonwealth has to make,” said Lewis, a leading political scientist who has published extensively on Marcus Garvey and Walter Rodney.

He said that Secretary General Scotland has a choice to make.

“That role can be interpreted by the secretary general in the same way that Sonny Ramphal interpreted his role as an advocate for the principle of political liberation and anti-racism, anti-apartheid,” he stressed.

For Shepherd, Scotland should “embrace the movement as an obligation and lobby for it to be a standing item on the agenda”.

Shepherd said the populations colonised were subjected to “the worst forms of terrorism” and the fight for reparation “is about justice and compensation from Britain to the majority of Commonwealth countries for the harms committed against them as well as for continuing harm.

“Most of these countries are poor and underdeveloped and their socio-economic conditions are not unconnected to the transatlantic trafficking in enslaved peoples, chattel enslavement, wealth extraction and general colonial and post-colonial harm,” she said.

The Commonwealth is a voluntary organisation of 56 countries representing 2.5 billion people. Its next major meeting is the heads of government talks set for October in Samoa next year.

King Charles III formally became the ceremonial head of the Commonwealth last year, following the death of his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, who led the organisation for more than 70 years.

The British monarch is not automatically head of the Commonwealth. Member states chose Charles to succeed his mother in 2018.