Creating a personal fragrance in France

Many of us grew up in post-independence Jamaica with assorted popular fragrances such as Khus Khus, Cacique, Brut by Faberge, and Old Spice. And there was also Aqua Velva, a fragrance that ran a clever ad in Spanish on the Jamaican JBC TV, urging legislation to protect women from men who wore Aqua Velva!

My first encounter with fine fragrances was in the late 1970s on a trip to Haiti when I ran into Christian Dior, Monsieur Linvin, and Givenchy fragrances for US$10 each at the duty-free shops at the airport in Port-au-Prince.

Since then, interesting fragrances have been on my radar, and I recall browsing fragrance stores once in Tokyo, Japan, in the 1990s while on a Japansplash tour with Stitchie and Buju Banton. Banton bought Cool Water by Davidoff in the attractive blue bottle, which was new at the time. Stitchie opted for a Japanese fragrance. I discovered right there a local cologne called Zephyr by Shisheido, which is the only fragrance I used for many years until it was discontinued by the manufacturer over 10 years ago. I was able to find it online once in a while, and I bought the last bottle I could find on eBay only a few months ago.

So I was intrigued when my travels took me to the south of France last month, and I discovered that I could create my own fragrance in a lab. I was in Nice, near a town called Grasse, where most of the fine fragrances of France are produced. The mild Mediterranean climate in the Maritime Alps triggers a profusion of exotic blooms, and extracts from these flowers are used in the secret formula for many treasured perfumes and colognes. I had visited Grasse several years ago, where I had extensive conversations with a ‘Nez’ who is a trained professional in the art of creating fragrances. ‘Nez’ in French means nose, and these experts must study for seven years to attain professional certification. France is, of course, the world’s leading producer of fine fragrances, and a large cadre of expert noses are needed to retain that global edge. France also produces the world’s most popular fragrance product, Channel No. 5, a consistent top seller for decades in the multibillion- dollar industry.

I planned a session for a Thursday afternoon with fragrance specialist Sasha Leroux. I arrived early at the workshop in a quiet part of the city that was only a twelve-minute walk from my hotel. I was enthusiastically welcomed with a glass of champagne and invited to take a seat. We chatted briefly, and within minutes, five other participants arrived from Germany, Saudi Arabia, and Texas. The first half-hour was spent learning about how fragrances are made, their origins in ancient Egypt, the role that flowers play in the manufacture of perfumes and the various types and strengths of fragrances. We are also enlightened about some of the unusual and unpleasant ingredients that are sometimes added to the formula to create a perfect balance: ingredients like whale vomit and deer testicles to create musk and secretions from the civet, a small, nocturnal mammal. The group exploded into laughter when Madame Leroux explained that a part of France’s dominance in the fragrance industry was due to the fact that French kings didn’t like to bathe, so fragrances became an essential part of the allure for nobility to visit the royal palace!

REAL WORK

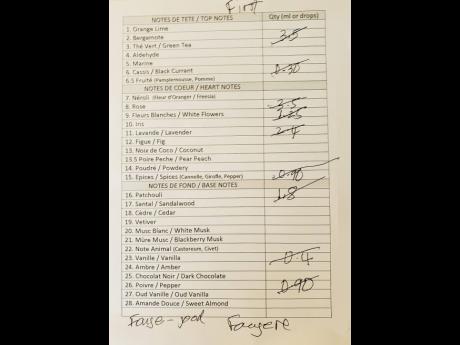

We’re now ready to create. Sasha walks us through a number of olfactory families of fragrances, including bergamot, green tea, cassis, spices, vanilla, and pepper. Some are warm and woody, some sweet and spicy, and others floral and fresh. Each work table is equipped with an array of numbered fragrances, mixing bottles, measuring devices, coffee beans to regularly clear the nostrils, and a formula card to log each ingredient carefully. We browse and select three notes that we love the most (top notes, heart notes, and base notes). Based on the individual choices, we get guidance cards, and then the real work begins, chemistry class-style, adding very specific amounts of various ingredients to the master mix. It takes about 30 to 40 minutes to mix about eight to 12 essences to bring each individual magic potion together. I immediately love my final crisp, clean citrus-like blend of orange lime, spices, and white flowers, with a splash of sandalwood, vanilla, and pepper. It is perfect, and I proceed to name it Chez David. But not everyone is happy with the outcome of their product. Gisela from Germany thought her creation was too floral, and with the help of Sasha, she spent another 20 minutes turning down the volume on the top notes, eventually bringing it to a happy place. At the end of the exercise, everyone was utterly thrilled that through diligence, we had created our own unique fragrance.

PERSONALISED ELEGANCE

Sasha pointed out that the fragrances would take on exciting new twists within a few days after the blend sits and mellows. She also informed us that the best way to spray is to the back of the neck, nearby the hairline, as fragrances cling to hair more steadfastly than they do on skin. Before we disperse, the formula for each creation is logged in a computer so that participants can reorder and have their fragrances shipped to them months or years later, as they wish. The perfumes were then placed in fancy bottles and beautifully wrapped with Sasha’s own personalised elegance. I suppose my fragrance was truly one of distinction, for I wore it in Montego Bay recently to the launch of Reggae Sumfest, and a stranger from a radio station who clearly knows a lot about fragrances approached and asked me what I was wearing. “My own fragrance,” I declared. But my answer was followed by that quizzical look as I was curiously scrutinised.

But back to France. “So Sasha, tell me, when is a French designer going to create a knockout fragrance blending the globally trendy Jamaican ganja or cannabis, lavender, and lemon grass?”

There was a long pause for reflection and then a measured reply as if the question pulled a trigger.

“You never, never know. Fragrance, like clothing, follows fashion, and the next season can always bring big surprises.”