‘War zone’ - Journalist says covering 1980 elections made him feel like war correspondent; did media play politics?

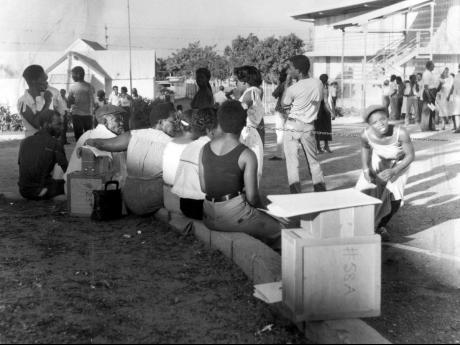

A clash of opposing ideological beliefs, armed political enforcers in garrisons carrying out the bidding of politicians, and a relentless zest for power or dogged determination to hold on to it. These, fuelled by a fight for scarce benefits and spoils, blended to produce a deadly cocktail of violence and savagery that exploded into Jamaica’s bloodiest elections in the run-up to the 1980 national polls, where more than 800 people were butchered as a result of political barbarism.

One journalist who traversed the political strongholds of both the People’s National Party (PNP) and the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), said the carnage he saw during the tumultuous election period prompted him to walk away from the profession after the polls.

“One of the reasons why I left journalism after the 1980 elections was because of the kind of carnage that I saw in terms of people being killed,” Lester Hinds, who worked as a reporter with RJR at the time, told The Gleaner.

When the barking guns subsided, which had been thrust into the hands of vulnerable young men, many uneducated, the corpses taken to the morgues were those of poor black Jamaicans who, for the most part, lived in inner-city communities or areas more popularly known at the time as ghettos.

“The political tribal violence in 1980 was staged in the inner-city communities, not up in Beverly Hills and uptown,” Hinds emphasised.

He said that for the most part, it was poor people killing each other over PNP and JLP politics.

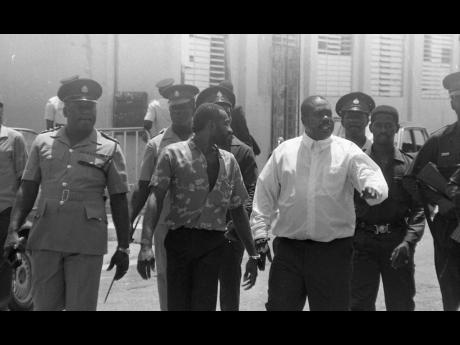

UNDER FIRE

Recounting an incident in Majesty Gardens in South West St Andrew during the election campaign that has left nightmarish flashbacks, Hinds said he received a call that there had been a killing in the volatile community.

Rushing to the area to cover, Hinds said that he first stopped at the Hunts Bay Police Station and discovered that its gates were closed, which came as a surprise.

“That night, the gates were closed, and police officers were on the roof of the building with high-powered rifles, and they shone the flashlight on us and realised it was RJR, and they let us in,” he recalled.

He said the police told them that they were aware of gunfire in Majesty Gardens but that the lawmen were not inclined to enter the community without “light” as they were awaiting the arrival of a Jamaica Defence Force helicopter with a floodlight.,

When they eventually entered the community with the army, Hinds said he saw an elderly woman, about 75 years old, “whose face was completely shot off and there was a seven-year-old who was also shot and killed. It was not a pretty sight going in there at that hour of the morning”.

“I think both sides were to be blamed for the political violence,” he said of the PNP and the JLP.

“As journalists, we also came under fire, literally came under gunfire, not that it was aimed at us, but because we were in the area covering.”

Hinds said that media practitioners at the time shared a cordial relationship although the competitive nature of the profession was never lost on them.

“We took the view that if you attack one reporter, you attack all of us, irrespective of which newsroom you worked for,” he stated.

The four major media entities at the time were The Gleaner, RJR, Daily News, and the Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation (JBC), now defunct.

He admitted that there were some journalists who were political “activists”, and they did not hide their advocacy. “They made no bones in terms of where they stood in relation to the political parties,” he added.

TIES FOR FREE PASSAGE

Wilbert Thomas *, another journalist who covered the 1980 elections, said that he established ties with notorious political enforcers at the time in order to get “free passage” in volatile communities to get the news.

Thomas named the dangerous Anthony ‘Starkey’ Tingle, leader of an Arnett Gardens, South St Andrew-based gang, and Lester Lloyd Coke, otherwise known as Jim Brown, Tivoli Gardens, West Kingston strongman, as contacts.

“It wasn’t like a big deal to have contacts with them,” said Thomas, who noted that they were viewed as facilitators who provided him with information in terms of what was happening in various communities.

“Those guys provided us with safe passage in certain communities. People seeing you with them, they were told not to interfere with you in terms of your job.”

Ewart Walters, a senior journalist who was working as a member of the Jamaican Foreign Service in 1980, said that the period leading up to the general elections was characterised by unending visits from the overseas press.

According to Walters, visits by the foreign press were “part of a destabilisation programme because as soon as the 1980 elections were over, they stopped coming. We have not had any more mass incursion of foreign press into Jamaica since the end of 1980. And before 1976, we never had it either. Nineteen-seventy six and 1980 were two very unusual years in terms of elections and election campaigns”.

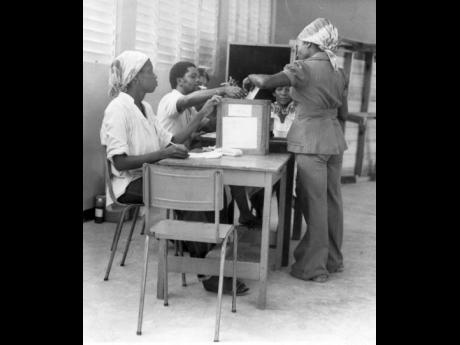

Walters argued that from Jamaica’s first general parliamentary elections under universal adult suffrage on December 14, 1944, until 1976, Jamaica had peaceful elections. He said that “nobody was trying to shoot anybody over power”.

However, he described the run-up to the 1980 elections as “a time of heightened terror. People would come up to you and say, ‘Who yu a defend?’ Your life would depend on what answer you gave.” The question was in relation to which political party the individual endorsed – PNP or JLP.

Politics was so divisive that a person who dared to show allegiance in public to one party or the other ran the risk of facing a violent attack.

MEDIA INTERFERENCE

The media did not escape criticism in the polarised political environment in 1980.

Colin Campbell, PNP politician and former Cabinet minister who was a journalist at JBC in 1980 and who was seconded to work with former Prime Minister Michael Manley as press secretary, dismissed claims that reporters at the state-owned statutory media entity were biased in carrying out their duties.

According to Campbell, then Opposition leader Edward Seaga called JBC “a cesspool”.

He defended those working at the entity at the time, saying they were professionals and resisted attempts by politicians to influence the news product.

“In those days, politicians and others did not have a lot of respect for the profession. They saw us as people to publish what they wanted to say, and this wasn’t only JBC alone. It permeated the profession, and it resulted in the interference in many news departments, not only at JBC, but The Gleaner,” said Campbell. He noted that RJR’s newsroom was more insulated from outside influence.

Further, he said that board chairmen facilitated some kind of intrusion, which resulted in strikes by media workers.

Immediately after the 1980 elections, Campbell said that reporters at the JBC, with the exception of three people, were dismissed by the Seaga-led administration following the JLP’s landslide victory.

“When they dismissed us and it went to the Supreme Court, it was rubbished in the Supreme Court. In fact, they surrendered in the Supreme Court because of all the nonsense and asked us to settle out of court,” he noted.

He explained that at the time of the settlement, the dismissed reporters had been out of JBC in excess of a year, and many moved on in other areas of the profession.

In the latter part of 1979, tensions heightened between sections of the media and the then Manley administration.

Hinds said that the indignation of the PNP could no longer be contained, and Manley led a march on The Gleaner’s North Street, Kingston, offices on September 25, 1979, protesting what he regarded as unfair journalism against his administration. The march ended with a warning from Manley: “Next time! Next time!”

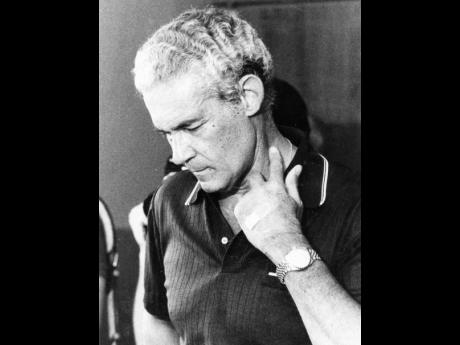

Then managing director of The Gleaner, Oliver Clarke, was of the view that Manley’s action was aimed at “bringing pressure on The Gleaner to influence editorial policy, or, indeed, to close the company” and launched a campaign to protect the free press, which he regarded as a critical pillar of democracy.

TARGET MANLEY GOVERNMENT

Walters argued that with the departure of Gleaner Editor Theodore Sealy, in 1976 and the subsequent appointment of Hector Wynter as the new editor, several members of the news-reporting staff were fired and replaced by about 15 opinion writers.

“They were saying the PNP administration was awful; Manley was dirty,” Walters said of the new Gleaner writers.

He said that The Gleaner painted the then Manley government as corrupt and a “Cuban appendage”.

Indicating that the new opinion writers had been recruited to target the Manley administration, Walters said that three months after the 1980 elections, most of the writers who had replaced career journalists left the newspaper.

The late 1970s into the mid-1980s marked the late phase of the Cold War when hostilities increased between the nuclear-armed then Soviet Union and the West.

It was a time when the Michael Manley-led regime in Jamaica experimented with “democratic socialism” even as the administration enjoyed close ties with the Communist-led Fidel Castro regime while the Edward Seaga-led JLP was closely aligned to the United States government.

* Name changed to protect identity