COVID-19 dominated the world

Obesity and poor outcomes from men, in particular, are among the key issues to have emerged from Jamaica’s battle with COVID-19 last year, 10 months to the date since the first case of the deadly and highly contagious virus was confirmed on the island.

For its immense, unprecedented impact, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) – a previously unknown form of the virus – was unrivalled as the newsmaker of 2020.

The virus is spread mainly between people, when an infected person comes in close contact with another person, through respiratory droplets such as sneezing and coughing or even surface touching.

COVID-19 rose from its nest in China in November 2019, and embarked on a world tour, shutting down countries and sending people, those not in defiance of restrictions, scampering for refuge from an invisible enemy.

The tumultuous period was first spurred by the January 30 declaration of the disease as a public-health emergency of international concern.

Then on March 11, the ‘pandemic’ label was added, which the World Health Organization (WHO) said was because of “alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction”.

OBESITY MAKES IT MORE DEVASTATING

Jamaica’s entry into the global count on March 10 with a confirmed case brought the figures to 116,135, but the scare those numbers triggered at the time would be dwarfed when compared with the 81.5 million infections up to December 31 and the 1.8 million persons who lost their lives.

Jamaica, up to year end, confirmed 12,915 COVID-19 cases from 138,968 tests, with 303 deaths.

From those numbers, a picture began to emerge of the differentiated impacts well beyond the economic fallout, which is expected to cost the economy upwards of nine per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP).

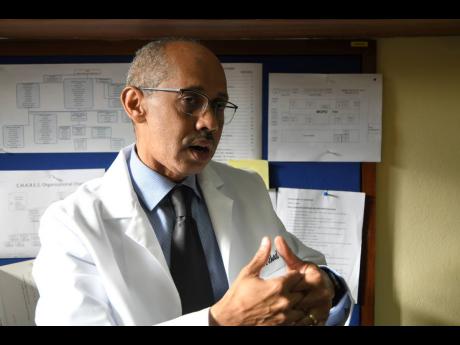

Professor Michael Boyne, the head of the Department of Medicine at the University Hospital of the West Indies (UHWI), has declared that Jamaica is fighting two epidemics – the coronavirus and non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

Many of the NCDs – such as diabetes, heart diseases and hypertension – form part of the range of comorbidities that make people more susceptible to COVID-19.

“What also makes it a bit more deadly for us, too, is obesity. The higher your weight or body fat, the more likely, for reasons which we don’t quite fully understand, it makes it (COVID-19) more devastating to us,” said Boyne.

“If you look at many of the persons who have not done so well, you would have also seen that one factor that was common was obesity.”

Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health, stated a WHO definition, which added that a body mass index (BMI) over 25 is considered overweight, and over 30 is obese.

The conditions are heavily tied to diet and the consumption of energy-dense foods that are high in fat and sugar, worsened by lack of physical activity – making the body ripe for diseases such as cancers, hypertension, diabetes, among others.

The situation is stark here, where one in two Jamaicans (54 per cent) is considered overweight, based on the latest data available through the 2016-2017 Jamaica Health and Lifestyle Survey.

Noting that obesity is also referred to as an inflammatory condition, Boyne explained that this presents an advantageous environment for the coronavirus.

Fat in the abdomen, explained US-based scientist Anne Dixon in ScienceMag, pushes up on the diaphragm, causing that large muscle which lies below the chest cavity to impinge on the lungs and restrict airflow.

This reduced lung volume leads to collapse of airways in the lower lobes of the lungs, where more blood arrives for oxygenation than in the upper lobes.

COVID-19, which attacks the lungs, gets a big boost in those situations.

National data on the breakdown of confirmed but recovered COVID-19 cases with co-morbidities was not immediately available, but Dr Karen Webster-Kerr, national epidemiologist, said the death cases give an indication of the distribution of lifestyle diseases.

Some 92 per cent of the 302 deaths up to December 30 were linked to one or more risk factors – cardiovascular disease (54 per cent), diabetes (41 per cent) and renal disease (10 per cent).

Over 215 of those who died were 60 years and older, a vulnerable cohort because of the increased likelihood for comorbidities.

And while obesity directly accounted for 11 of the deaths, Boyne argues that further investigation is likely to result in an obesity link with the other conditions.

VERY PRONE POPULATION

Globally, the issue has attracted significant attention.

International researchers last August released data showing that of 399,000 obese patients who contracted COVID-19, 113 per cent were more likely than people of healthy weight to land in the hospital; 74 per cent more likely to be admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU); and 48 per cent more likely to die, according to data from the Obesity Reviews journal.

With those predispositions, it’s “interesting” that the devastation in countries such as the United States has not been similar here, noted diabetes expert, Professor Errol Morrison, who added that combined, diabetes and hypertension affect almost one in two Jamaicans.

“With obesity on top of it, we have a very prone population,” Morrison told The Sunday Gleaner.

“Whether the virus will survive as long and as well and effectively in the hot climate as it does in the northern cooler climate is also a question. It should not be pushed under the carpet and say ‘nonsense’. There is some truth in it and we need to look at it … it is a multiple story.”

For Professor Boyne, the comparatively limited negative health impacts are a “wonder”.

“I’m just amazed that we have not been sicker but I’m also very thankful,” he said, noting that “there’s a lot of speculation” about the differentiated outcomes.

“It might also be that we have the benefit of learning from persons overseas,” he reasoned.

Assessment of trends and emerging concerns

Professor Michael Boyne, the head of the Department of Medicine at the University Hospital of the West Indies (UHWI), was among several health professionals from the UHWI, the leading institution in the local response to COVID-19, who spoke with The Sunday Gleaner about their assessment of trends and emerging concerns arising from the cases.

Since the first case in Jamaica in March last year, the intensive care unit (ICU) has seen more than 200 COVID-19 patients, along the continuum of mild, moderate and severe cases.

The first critically ill patient admitted to the unit was a male returning resident from the United Kingdom, who was among the passengers from a March flight from which a woman was confirmed as Jamaica’s first COVID-19 positive patient.

That flight triggered the wave of border closures, which was limited at first to the United Kingdom (UK) and eight other countries before a full lockdown that stretched into July amid outcries from citizens stranded in foreign lands and on the high seas.

“The symptoms actually started shortly before he left the UK, which he just probably thought were symptoms similar to the seasonal flu,” disclosed Dr Kelvin Metalor, head of UHWI’s anaesthesia and ICU, of the first critically ill patient in Jamaica.

The man’s condition deteriorated and he was later referred to a public hospital by his general practitioner for a few days.

“At the time that he arrived in our institution, he was extremely ill. He was already intubated … he still remains one of our unique cases. A very challenging patient to manage but, as you know in cricket, it set the innings.”

The patient survived but, as Metalor grimly admitted, “a lot” of patients did not make it.

FEAR OF THE UNKNOWN

One of the main challenges with the patient revolved around the ‘fear of the unknown’ and the rich absence of information to guide healthcare workers.

“The exact modes of transmission of this particular virus were not all elucidated. The infectivity was still being studied,” Metalor shared, joining the lament of colleagues around the world.

“There was a lot of fear; a lot of apprehension among the staff. Persons didn’t know what to expect; they didn’t know how easy it would be for them to be contaminated … there were no specific treatments available.”

He added: “It was still a very unknown territory at that particular point in time. It was difficult to get staff to work with the patient, and we could understand the position of the staff because a lot of them didn’t know what to expect.”

As the science quickly developed and treatment options became more defined for this novel coronavirus, the initial fears which were resident among the wider population, even resulting in nurses being shunned, subsided among the critical front-line cohort.

Best drugs for treating COVID-19

Steroids, now a “mainstay” in the treatment of COVID-19 cases, said Professor Michael Boyne, the head of the Department of Medicine at the University Hospital of the West Indies (UHWI), are critical to helping control inflammation by “toning down” an overactive immune system.

The more common steroids in use include dexamethasone, whose credibility in fighting COVID-19 is built on tests in the UK where, for patients on ventilators, the treatment was shown to reduce mortality by about one-third, and for patients requiring only oxygen, mortality was cut by about one-fifth.

The main drug regimen at the UHWI is dexamethasone, with an alternative being hydroxycortisone, the medics said.

In September, based on “moderate certainty evidence” of a mortality reduction of 8.7 per cent and 6.7 per cent in severely or critically ill COVID-19 patients, the World Health Organization (WHO) “strongly” recommended dexamethasone, hydrocortisone or prednisone be given orally or intravenously to those classes of patients.

But it advised against their use in treating with non-severe COVID-19 cases, unless the patient is already taking this medication for another condition.

“For dexamethasone, it is 6mg once a day for 10 days,” Boyne said, outlining the dosage used.

“We’ll also use remdesivir, which has got a lot of press. We use 200mg once a day on the first day and then 100mg every day for five days. We tend to use the remdesivir in the earlier stages of the disease.”

Anti-blood clotting drugs are also an important part of the treatment protocol.

“We’ve also found that in persons who have had COVID-19, that they are at a greater risk of developing blood clots. We give them anticoagulants and we use enoxaparin, which we give as a dose of one milligram per kilogram twice per day, and that’s an injection,” said Boyne.

That latter treatment tends to go for moderately to severely ill patients.

PRONING

The drug regimen that’s administered is only part of the treatment protocol, emphasized Dr Kelvin Metalor, head of UHWI’s anesthesia and ICU, who insisted that the personnel around patients are fundamental, especially in the absence or shortage critical resources.

This has been highlighted mainly in the need to skilfully turn patients on their stomach, a process called proning that’s done to boost oxygenation and lung support, especially for patients in respiratory distress.

It’s also where the issue of obesity complicates things, the senior doctor admitted.

“One of the ways that you manage COVID is that you try to get them on their tummy and if you have a lot of fat around your tummy, it’s very difficult to get them to prone,” Metalor said.

“Either they cannot self-prone because they are physically limited or if they are intubated, it’s very challenging to be able to take all of that pressure away from the tummy and that affects our ability to adequately ventilate them.”

Proning beds are available but the cost is prohibitive, with one unit going for at least US$120,000, which is just one hurdle, since other issues include suppliers unwilling to sell outside their jurisdiction because of the lack of local technical expertise.

The concern for men and the impact on them have also been among the revelations for the local experts.

Dr Karen Webster-Kerr, national epidemiologist, said there’s no definitive reason why Jamaican men are more likely to get symptoms than women.

“Men are more likely to have more severe symptoms than women and men are more likely to die than women, significantly so,” she revealed in an interview in mid-December.

“We also control for other factors. We control for age and co-morbidities and it did not change the association. One may contribute more but it did not take away the significant difference between male and females.”

The health seeking behaviour between the sexes may offer some explanation, the epidemiologist said, however.

“They (men) are less likely to seek help than women. They tend not to know if they have co-morbidities. Two-thirds of men don’t know that they have hypertension, diabetes and so would not be treated. If you have uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes or another chronic illness, your outcomes will be poor. That could be a possibility,” Webster-Kerr noted.

Of the 302 COVID-19 deaths that were recorded in Jamaica up to December 30, men accounted for 56 per cent (170) and therefore with a case fatality rate of 2.9, compared to 1.9 for women. The disaggregated data for other confirmed cases was not available.

JAMAICA NOT UNIQUE

Jamaica is not unique in the disproportionate outcomes for men, with scientists in a July paper for United States public health response arguing for a consideration of the biological and psychosocial factors that put men at risk.

They noted that up to that time, although there was not apparent sex differences in the number of confirmed cases, more men than women died from COVID-19 in 41 of 47 countries.

Subsequent studies have also raised concerns about the so-called “shadow pandemic” of violence against women and girls exacerbated, the World Bank said, by the stay-at-home orders, forcing some victims to be locked up with their abusers.

“Gender-based violence has gone up exponentially,” Reuters quoted Alison Drayton, the Jamaica-based director and resident representative for the UNFPA’s sub-regional office.

Stay-at-home and work-from-home orders backed by extended night-time curfews were pretty much national policy and even legal mandates.

COVID-19 trauma still lingers in Corn Piece

For some communities, especially early on in the outbreak, quarantines and special curfews were implemented to control the spread of COVID-19.

Bull Bay in St Andrew, home base for the first confirmed case in March, which was imported from the United Kingdom; and Corn Piece Settlement in Clarendon where the first confirmed COVID-19 deceased person, a 79-year-old man with United States travel history, lived, were among the communities that faced stiffer measures.

The Sunday Gleaner revisited Corn Piece in December but relatives were reluctant to talk about what has happened in the intervening months.

Residents, however, were crying for attention as they said they felt abandoned and cut off from the rest of the country.

The quarantine might have been lifted and the security forces long gone, but the memories for some still linger.

For one mother, Shanique Malcolm, the quarantine left a negative effect on her young daughter who she said has been traumatised by the presence of the police and soldiers in the area.

“Right now, she fraida di police dem. If she see one police right now, she start move shaky and run go hide,” Malcolm shared, pointing out that the tents were set up in the vicinity of her home and her daughter had first-hand view of the police and soldiers with their guns.

“Dem walk through as dem like, dem do anyting as dem like, so mi feel seh a dats why she fraida dem now, cause she see the gun and ting every day,” she related.

According to the mother, she tried on many occasions to reassure her daughter that the police would not hurt her, but it doesn’t seem to be working. She said her daughter still shakes when she sees them and she has had on many occasions to hold her for her to be reassured.

Rastafarian Ray Washington Williams said though thankful neither he nor any of his relatives contracted the coronavirus, he, too, has been left shaken from the ‘bad treatment’.

“Mi nuh eat certain foods, especially di tin food, and a one time dem gi mi fish,” he said of the supplies they received from the authorities during the lockdown, adding that what he went through pressure his head up until now.

COMMUNITY NEEDS ATTENTION

While some residents might have had different experiences during the lockdown, they all agree on one thing when it comes on to the community – it needs attention.

“Look at the big football field. We need a community centre, something wey young people can have Internet. We not even have a basic school in the community,” Williams said, a sentiment also shared by Malcolm and a shopkeeper close by who said it has been months since her daughter had any lessons, as she cannot afford the data plan to facilitate the online classes.

In a statement to Parliament on October 6, Health Minister Dr Christopher Tufton acknowledged the mental health strain for Jamaicans who were forced into near isolation at home, and children unable to interact with their peers, which led to the launch a $20 million support programme.

Heading into 2021, the local authorities, along with the medical practitioners, admit that what Jamaica has been experiencing in terms of case count may only be the “tip of the iceberg”.

It doesn’t help that the year ended with Jamaica confirming four cases of the COVID-19 variant found in the UK, for which there is little data on its full impact.

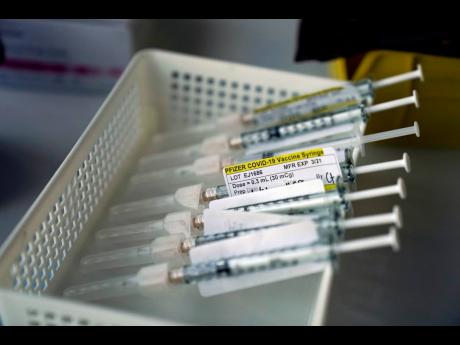

Months of research and trials resulted in the UK, in December, granting approval for a COVID-19 vaccine. Jamaica’s chances are tied up COVAX, a global collaboration led by the World Health Organization.

Cecelia Campbell-Livingston also contributed to this story.