Man with renal failure pleads for donor

As kidney disease becomes more prevalent among Jamaicans, most struggle with cost of treatment

Chronic renal failure is a major public health problem in Jamaica, and this is placing added financial burden on the healthcare sector as well as on the growing number of patients who need care.

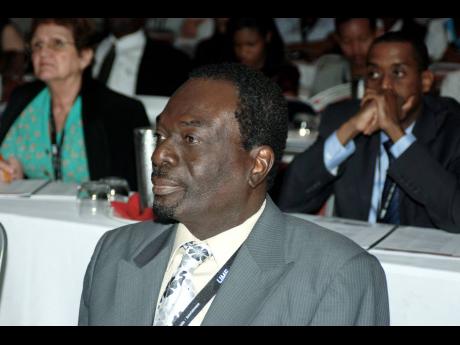

Professor Emeritus of Nephrology at The University of the West Indies Everard Barton said the number of persons suffering from renal failure in Jamaica is about 600 to 700 per one million. He said the figure is about 1,000 per one million people among persons aged 65 and upwards.

There are more than 2,000 persons currently on dialysis, and a growing number of patients waiting at the Cornwall Regional Hospital (CRH), Mandeville Regional Hospital, Spanish Town Hospital, Kingston Public Hospital (KPH), and to a lesser extent, at the University Hospital of the West Indies (UHWI). Adding to the backlog is the current COVID-19 crisis confronting public hospitals, forcing persons with end-stage kidney disease to seek treatment at private facilities, if they can afford it.

Forty-year-old Michael Everett, a Portmore man who was diagnosed with kidney failure in June, is among those who are having difficulty keeping up with the cost of dialysis and dieting requirements.

Appeal for help

Everett has sent out an appeal for help, having exhausted all his savings on dialysis since he was first diagnosed with kidney failure.

“I feel some pain and after them check me at the clinic, they immediately referred me to the Kingston Public Hospital where I was admitted the same day, and after more checks, they found out that I have kidney failure,” Everett told The Gleaner.

“The news came as a shock to me. I took it to heart and my blood pressure went up very high, so they had to keep me in the hospital for two weeks to get it under control.”

According Everett, doctors at KPH recommended that he received two rounds of dialysis per week, but he could only get one per week because there are many other patients on the waiting list. Upon his discharge from the hospital, he was given a referral to a private facility where he would have to pay to get his weekly rounds of dialysis.

“I check a couple and some were asking for up to $25,000 for one treatment. I couldn’t manage that price so I checked around and found one that charge $15,000,” Everett shared.

He added, “Even with the $15,000 for one treatment, for me to come up with $30,000 per week for the two treatments the doctors at KPH ordered, and to find money for special diet without a source of income, is causing me to be more sick,” he declared.

“I can’t work again with this catheter attached to my chest,” he said while lifting his shirt to show the area where the tube is affixed. “I don’t have nobody to help me, all my savings gone (and) there is family but no family. I have to rely on friends for help now, and I don’t know how long this will continue,” the kidney patient revealed.

Barton agreed that the cost for dialysis is beyond the reach of low-income Jamaicans, which he said is driven by the fluid that is used during the process.

He noted that the cost to the public health sector will not allow the hospitals to give this service free, except for the UHWI that has in place a fee that is far less than private providers to administer more than half of the recommended weekly treatment.

“I know what we did at the university hospital is that we have started Peritoneal dialysis, which is another type of dialysis that is done through the belly, and I know KPH is doing it also, and Cornwall Regional to a limited extent.”

Can be done at home

Barton said this type of dialysis will help to reduce the waiting list and give hospitals the capacity to perform more weekly dialyses.

In addition, it can be performed by the patients themselves at home, creating greater convenience for them. He said the cost for this type of dialysis could prove to be even less expensive, depending on the source of the fluid that is used in the process.

But with Everett unable to afford even this type of dialysis, his only other option would be to have a kidney transplant, which is also an expensive process and requires aftercare treatment and medication to assist his body to assimilate to the new kidney. Barton said this is required even when there is a perfect match.

“I would prefer to get a transplant but I don’t have nobody to give me a kidney. I am begging anyone out there who can give me a kidney to help me out please,” Everett pleaded.

Barton, who founded the Caribbean Institute of Nephrology, said there are candidates whose relatives have indicated their willingness to be kidney donors and are ready for transplants, but the process has been delayed due to COVID-19.

For Everett, who has no family donor, he will have to be placed on a waiting list for a matching kidney, and this could mean a considerable waiting period.

“We will have to hit the road again when it is physically convenient to reset the national campaign for deceased donor kidneys,” Barton assured, adding that the outreach has to be carefully assessed.

In the meantime, Everett is hoping that he will get help as he struggles to cope with the disease.