Kwanza is not a black Christmas

Parts of the story of Jesus Christ are that he was conceived immaculately by a round, young virgin at Nazareth; born in Bethlehem of Judea; grew up in Nazareth, among other places; and died at Calvary on a cross. These are places that are located in what is now known as Israel to some and Palestine to others.

The gospel also referred to him as the Messiah, the Son of the living God. His crucifixion is said to have been the ultimate sacrifice to save the world from sin.

No one knows for sure when it had started, but every year, for centuries, December 25 is celebrated as the anniversary of His birth. Yet, what started out as a religious observance has evolved into a worldwide season of commercialism. And in many respects, the social and commercial elements of Christmas have superseded its religious significance, and the biggest Christian holiday is now the biggest shopping and spending season in the world.

Not everybody is enamored by Christmas and what it represents. Some regard it a season of pagan festivities, contrary to the principles of Christianity. Islam and Judaism have even rejected Jesus Christ as the Messiah, the one to redeem the world. Muhammad is the prophet that Muslims say Allah had sent to Earth, while the Jews are saying that the Messiah is yet to come.

Apart from Jesus’ birth, Christmas is represented by a lot of symbolism, such as the crucifix, the Virgin Mary, Baby Jesus in a stable, thee wisemen following a star, Christmas trees, Santa Claus and his reindeer, etc. These symbols mean absolutely nothing to many people.

They have not subscribed to its religious, sociocultural and commercial significance. And, since December 1966, African Americans have been celebrating Kwanza, which many people regard as a wholescale rejection of the Eurocentric nature of the Christmas story, at the centre of which there is a white Messiah.

Yet, Kwanza started out as a cultural, not a religious holiday by Maulana Karenga, a professor and department chair at California State University, Long Beach. “The celebration of Kwanza is about embracing ethical principles and values so the goodness of the world can be shared and enjoyed by us and everyone,” he said.

It was established mainly for African Americans to reconnect with their roots and heritage, and that was why an African word was selected for the holiday’s name. Also spelt ‘Zwanza’ or ‘Zwanzaa’ and pronounced ‘Kwahn-zuh’, it originated from a Swahili phrase, Matunda ya zwanza, which means ‘first fruits’.

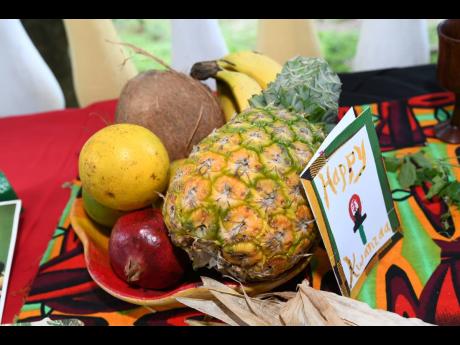

There are also seven symbols of Kwanza. Celebrants drink from the unity cup (kikombe cha umoja) in honour of their African ancestors. The kinara (seven-candle holder) symbolises stalks of corn that branch off to form new shoots. Fruits, nuts, and vegetables that remind celebrants of the harvest fruits that nourish the people of Africa are represented by the Mazao.

The Kwanza symbols themselves are arranged on the mkeka, a mat made of straw or African cloth, depicting the foundation upon which communities are built. Traditionally, an ear of corn (vibunzi) is placed on to the mkeke for each child present.

The seven candles of Kwanza are collectively called mishumaa saba. Each represents a day and is lit on that particular day. They are arranged in the kinara – three red ones on the left, three green ones on the right, and a black one in the centre.

Red represents the blood that is shed in the struggle for freedom, black is for the colour of the people, and green symbolises the fertile land of Africa. They are the same colours as the UNIA established by Marcus Garvey.

Kwanza celebrations were introduced to Jamaica by the late Queen Mother Mariamne Samad at her home in Havendale, St Andrew. It would go the entire length of the season, from December 26 to January 1. Over the years, the observance of Samad’s Kwanza dwindled to just one evening, on January 1.

It is a time of feasting, sharing and reflection, not to observe the birth of an African deity. It is widely regarded as ‘black people Christmas’. But, it is not. Christmas is about the birth of Jesus Christ. Kwanza is not.

From it started in the United States in 1966, it has been observed by black people in the diaspora to different degrees. Right here in Jamaica, there have been some people who, over the years, observe it on a minor scale. The late Queen Mother Mariamne Samad was the most consistent celebrant over the years.

Kwanza TEACHINGS

Not only did the Garveyite celebrate, but she also hosted gatherings and taught people about Kwanza and other black-people-related topics. “I started a group of women wearing beautiful African outfits. I started Kwanza. I started the dashiki. I started teaching classes,” she said in a conversation about her achievements and legacy.

Samad was born in the United States, where Kwanza is big, and became a member of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. She got married to a Jamaican with whom she settled upon his return to Jamaica after he retired. The last Kwanza she observed in Jamaica was in 2019. She made the transition in November of that same year.

Despite the efforts of Samad and a few others, Kwanza has not caught on in Jamaica as they had hoped. Christmas is still a big holiday here, where Christianity is the biggest religion. “Kwanza will never be popular in Jamaica because the majority of Jamaicans celebrate Christmas, and also, many Jamaicans reject their ties to African identities,” Sophia Walsh-Newman, a performance artiste and teacher of all things black, told The Gleaner recently.

Some people even see Kwanza as competing against Christmas. To this, Walsh-Newman said, “For me, Kwanza does not replace Christmas. Although I do not celebrate Christmas, I think Kwanza and Christmas can coexist for some. However, if you truly live the principles of Kwanza on a daily basis, the concept of Christmas will naturally be rejected.”

Walsh-Newman has been celebrating Kwanza with her children, family, friends and community for more than 30 years. The woman who referred to herself as a “returnee”, said she had organised a Kwanza celebration for the past 35 years and did not plan to stop doing so. “As long as I am in Jamaica during Kwanza, there will be a celebration,” she declared at an observance at her St Ann home last Thursday. It was actually a pre-Kwanza event, held on that day for a variety of reasons.

Central to everything was a table replete with symbols representing various elements and principles of Kwanza. Food was also in the mix, for, as with Christmas, Kwanza is a time for feasting, giving and sharing. In speaking with The Gleaner after the event, Walsh-Newman said, among other things, “As an African woman, Kwanza resonates with me culturally. It allows me to fully express myself and share my experiences and traditions.”