Michael Henry seeks to inspire others

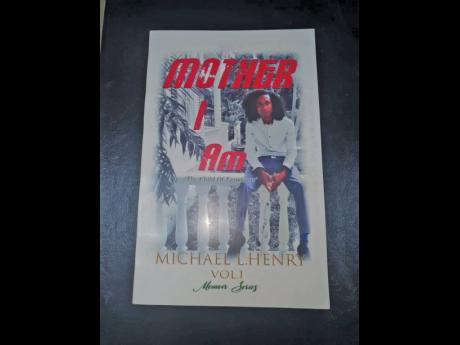

Michael Henry knows what it is like to be lonely, missing his parents, and trying to find acceptance in the wrong crowd. He opens up on his journey in his book, Mother I Am: The Child of Emigrants.

Henry, born in Kingston, was sent to live with his grandparents in Raymonds, Clarendon. As Christians, they ensured he went to church and got involved in church activities. Those days, Henry said, were the best times of his life.

All that changed when his grandfather died, after which his grandmother’s health went downhill, and she soon passed away, too.

When he was nine, Henry was sent back to Kingston to live with his parents. The family unit broke apart when his father had an affair, and his mother decided she would not stay “in that setting” anymore and went abroad.

“Shortly after she went abroad, my father, he saw a way wherein he could build a better life, as he realised it was only him and me; so he went away as well to the UK,” he said.

Henry, who passed his GSAT exam for Camperdown High School, said his mother left when he was in the seventh grade, and one year later his father followed suit.

“Everything changed. The stable home that I was used to was no longer there. My siblings were no longer around me; I was always around my neighbours, who are really strangers, and I started to take on the lifestyle of them – just like a gang lifestyle; smoking weed and mixing with the wrong sort of company,” Henry shared.

Feeling betrayed and alone, he said he felt like there was no one to offer him the love, care and comfort he was used to – just as his grandparents gave him.

THUG LIFE

He turned to ‘thug love’ and adapted their lifestyle. To be accepted, he did the things they were doing just to feel as though he belonged. It wasn’t long before he developed the lifestyle of “a street boy,. he said that in the midst of all that, something he was taught by his grandparents kept him struggling to finish school; he ended up getting a ”couple subjects”. His grades were too poor to graduate; however, the principal didn’t want to give up on him, so he was allowed to attend lower-sixth form.

Henry never made it to upper sixth as, he said, he realised he was getting too deep in the street life and if he continued on that trajectory – being on the streets and involved with guns and doing criminal activities – he would not live very long.

“Many of my peers were dying. Some of them police killed, and I realised that that wasn’t the script I wanted for my life,” he noted.

Henry said things started looking up for him when a church lady, who lived close by introduced him to the deacon of her church, who worked as a land surveyor. He gave him a job as his assistant and started mentoring him, encouraging him to get out of the environment he was in. His lifestyle caught up with him when police raided his apartment and found ganjal. He was charged for dealing in and possession of the drug.

OWN UP

“The don who had the same charge told me I should own up to everything (including his). I did and it messed up everything, as my mother had to discontinue the filing process for me,” he said.

He decided to leave Kingston, as the judge warned him that he had to get away away from the environment and turn his life around.

He also gives credit to Douglas Gordon, who mentored him after his ganja charge through his outreach programme, Last Project.

In 2014, when he returned to his grandmother’s community in Raymonds to live with his uncle, it was with a renewed mind.

“I wanted to make a difference in the lives of others who were living similar lifestyles (barrel children) who broke out. My aim is to inspire them, and the best way to reach a mass audience was by penning the book,” he told The Gleaner.

The book was launched at CanEx (Cannabis Exposition) in September at the Montego Bay Convention Centre.

Today, Henry makes a living from his art, which can be found at the gallery on Ward Avenue, Mandeville.