Heartbeat of surgery

Anaesthesiologists take patients through operating turbulence to safe landing

Consultant anaesthesiologist Dr Suzanne McDonald’s eyes welled with tears not once, but twice last week as she talked about a patient who she fought hard to save - but failed, and another for whom she could do nothing but sit with him until he...

Consultant anaesthesiologist Dr Suzanne McDonald’s eyes welled with tears not once, but twice last week as she talked about a patient who she fought hard to save - but failed, and another for whom she could do nothing but sit with him until he died.

All this during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Anesthesiology, is the medical specialty concerned with the total care of patients before, during and after surgery and includes anaesthesia, intensive care and pain medicine. Anaesthesiologists are the first ones in and last out of the theatre of any major surgery. As doctors, their training should insulate them from becoming personally attached to their patients, but the veneer is sometimes breached.The young woman, an obstetrics referral from Mandeville Hospital, died, and while the master technicians at the Victoria Jubilee Hospital (VJH) saved the baby, McDonald had wanted more.

“The ones that hit hardest for me are the ones that you know you fought for. You fight hard to keep them optimal before, during, and after the surgery. And somewhere in the process, you lose them.

“... So, of course, you beat up yourself. All the time. Oh, my gosh! We wouldn’t be human if we don’t, but that’s how you learn. But you toss and turn and relive the surgery in your sleep, and wonder what you could have done differently to have changed the outcome,” Dr. McDonald told The Gleaner.

‘YOU HAVE GOT TO LOVE IT, PASSIONATELY’

Although morbidity mortality sessions provide opportunities for members of the department to share difficult procedures, it still weighs heavily. The process is usually required again in a short time.Her eyes again brimmed with bright tears as she bemoans the very little they must work with at the Kingston Public Hospital (KPH), the regional trauma centre, the facility accessed by hundreds of thousands of poor Jamaicans annually.

During a visit to KPH last week, it was patently clear that much more than an overhaul was needed for the no-fee-paying, one-of-a-kind facility, which takes referral from every hospital in Jamaica, public or private. Still, relatives of all who must face the surgeon’s scalpel hope their relatives will all come back alive.

Dr McDonald says she came to medicine wanting to be an obstetrician, but while that was short-lived, not so her love for the surgical specialty. Anaesthesia, she says, made her more rounded and after “trying it out as an elective” she never left.

“I really find it to be an all-round interest, anaesthesia and intensive care. I know some people prefer anaesthesia and some critical care, but I like the exposure that it gives me, how it allows me to touch different areas of medicine and different people. I felt like I found my niche, and this is what keeps me going. With what we do, you have got to love it, passionately,” said Dr McDonald.

“My, our, services are required every day, 24 hours per day. We are the main specialty on the ground 24 hours per day. Whereas you can be on call in other specialties, we have to be there to administer the drugs, and things can happen so quickly. We have to respond to a lot of things all over the hospital, and everybody knows who they will find on the compound at any time on any given day,” she told The Gleaner.

Anaesthesia, like the medical school, attracts a large percentage of women, and there are about 80 of them to serve the entire island in both the public and private sectors. If possible, though highly unlikely, she stays far from neurosurgery and orthopaedics, and opts for general surgery and obstetrics. After 24 continuous hours of on-call duty, a day off must be taken. Covering KPH, National Chest Hospital and VJH often takes a toll on the personnel.Still, for Dr. McDonald, it is fulfilling.

“The poor people we serve are some of the most grateful people in this country. I come to work every day for them. They feel like somebody when you go all out for them, and they feel like we do. It is also amazing, because most times you don’t remember them, but they remember you and it warms your heart,” she told The Gleaner.

‘CLOSE, PRECISE MANAGEMENT CRITICAL’

For Dr Christine Stephen, head of the Department of Anaesthesiology at KPH, it is a very special role that requires a lot of planning to care for the patients who depend so heavily on their doctors’ steady hands and head. She says it is not always easy.

“You always have to plan for things going wrong. We are sort of like gatekeepers. We manage the surgeons, we manage the surgery. You think about what is in front of you, what could be in front of you, all the things that can go wrong and be prepared to manage them, because things happen all the time. Preparation is key…” she explained.

Smooth sailing is required, but sometimes there is turbulence.

“You want the smooth sailing, and that’s often what it is, and that matters. It’s like flying a plane; the takeoff and landing are critical. And sometimes during the flight, maintenance is rocky and you have to maintain calm. Keep steady hands at the wheel. Most people will be OK; you just tweak, tweak, tweak.”

“Knowing what to do often comes from experience, and oftentimes the junior doctors will say to us, ‘We are the pulse of the hospital.’ They often say, you guys carry the hospital, it’s a whole production. Females look for the fine details. And they are going to find it. This is not to say males are not thorough, but if something is missing somewhere, the female is going to find it,” said Dr Stephen.

Close and precise management are critical and require consultation and agreement. Sometimes it comes down to the anaesthetist saying, “Well, you can’t put the patient to sleep.” Acting in the best interest of patients is their job, and when death is unexpected it is jarring, but does not stop preparation for the other surgery.

“The patients don’t know this, but you toss, you turn, you vent, you ruminate, you go through over and over again. What could I have done differently. How could I have made this better; and it weighs, and it takes a toll. I felt like it would get easier over the years, but I don’t know that’s true, because each time it’s another family that you have to deal with. You eventually move on, but it influences your practice, and that’s how you get your experience.”

“We do have the benefit of the birds’-eye view. You’re managing patients; they come for a particular surgery and they are being managed by a team. So each surgeon focuses on his particular area. I now have to look at everything and take everything into consideration. So someone will say, the cardiologist says I am fine for surgery. By their definition the patient is OK. He or she will do their investigation and tell me what those say. I now have to interpret what that says … . But a lot of time they come in for something and something else interrupts it. A good surgeon listens to the anesthesiologist,” said Dr Stephen.She says surgical teams are usually uneasy when the anaesthetist is silent.

‘EVERYTHING WE DO NEEDS TO BE SAFE’

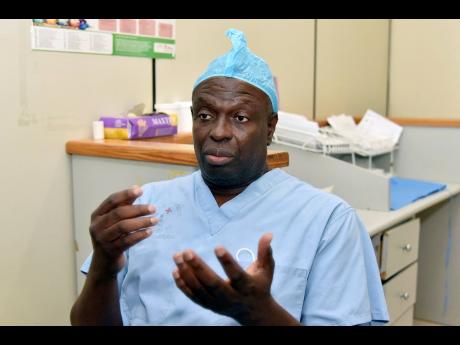

Dr Brian James, president of the Medical Association (MAJ), is a paediatric anaesthetist at Bustamante Childrens Hospital. He is among the most experienced in Jamaica and fell in love with anaesthesia after divorcing ophthalmology.

“I realize that I did not like ophthalmology, not even in the least,” he said.Instead, he found anaesthesiology to be “exciting”, and promptly enrolled in a postgraduate programme in the United Kingdom. While there, he became active with paediatric anesthesia and on completion - though his services were need at KPH - his post was at BHC. Within months after returning, he rejoined the staff at BCH and is still there today, more than three decades later.

“I am not 100 per cent sure why children are so fascinating. But it may have something to do with their innocence. You help somebody who is completely without hang-ups and baggage, then you actually see the results of what you do way more clearly than these other people with all these special requirements. All a child needs is to feel and function better. Also, children, because they tend not to have multiple physiological derangement (cormorbidities), when you do something for them, it tends to get the results more completely than an adult,” said Dr James.

Their innocence is the great appeal to him, and sometimes his patients come straight from the womb.“We do a lot of congenital abnormalities. We are the only hospital in the Caribbean with paediatric specialties. We have nine paediatric subspecialties among them are: general surgery, ENT, plastic, cardiac and neurosurgery,” Dr James explained. He recalls just recently having an eight-day-old “difficult patient”, with some of the bowels not in place.

Outlining the two main components to anaesthesia, he says anaesthetists are required to create the optimal condition for surgeries, including providing high or low blood pressure within the patients. Some surgeries require that the patients not be breathing and their hearts stopped.

Safety is the second component.

“Everything we do needs to be safe. I am a double-checker, to the point where people get upset with me,” he said, adding that they are called ‘obsessive compulsives’. Major surgeries require patients receiving at least seven drugs, and the anesthesist must know how each interacts with each other. Pharmacology and physiology are critical to the work of the anaesthetists and are often compared to the pilot’s console.

“I tell people that the anaesthetist is the first person to go into the theatre, because he or she has to prepare the patients, and at the end of the operation, you have to be there to wake them up and transfer them to the recovery room ... .” said Dr James.

He is liked by his surgical teams and was recently highlighted on social media for choosing surgery music and ordering food for the team. Some surgeons, however, want no sound, and music in the theatre was often a prior “negotiated arrangement”.

‘PLANNING, PREPARATION ARE CRITICAL’

Consultant cardiac and critical care anaesthesist at the UHWI Dr Jason Toppin is head of the Intensive Care Unit there.

“Everything bigger than simple surgeries requires an anaesthesiologist,” and knowing how much is enough to put you under when required, is a big part of training, he said.

“There are huge variations in putting someone to sleep. How big someone is, how old they are, what drugs they are on. But much of it is monitoring the patient, to say this person needs some more. The primary medicine we use to put people under is giving them a gas to breathe. During the surgery you may adjust the level, and give additional medication. If the surgeon needs you to relax, we give you drugs that cause temporary paralysis,” he explained to The Gleaner.

Leaving the theatre is almost a no-no, but if it must happen, it can be for no more than seconds, and the surgeons, anaesthesiologists and patients are the critical thirds in the whole.

“A big part of what I do is to put the patient at ease. I can do some surgeries where the patients are awake and some are asleep. So you have to know what surgery is best for a particular patient. But there is no no-risk surgery. And I still need the adult to understand the benefits, as well as know the risks,” he said.

The practitioner is constantly aware of all the things that could go wrong. This makes planning critical. When the unexpected happens, the help of colleagues is important.

“Planning, planning and preparation are critical,” he said.

Dr Toppin said some surgical teams are comfortable with music, while others want nothing. Music, however may be used to calm the patient, and surgeries can begin as early as 10 minutes to an hour before knife goes to skin. Waking up the patients after surgery is also studied. Using the airplane analogy, he said landing begins as much as 45 minutes before touchdown. The waking process is also gradual, and once the surgery is over he starts to decrease the anaesthesia.

Knowing whether a patient will wake up feeling pain or not is his job, and some surgeries are more painful than others. A pot-smoking, 20-year-old male is likely to get more painkilling medication than an 80-year-old.

“The young man is going to need more medication for pain, but he metabolises everything and is more likely to have pain, so I am going to give him more pain medication. In general, older people need less medication, but the ganja smokers, they are the ones who wake up and fight and are confused from agitation,” he explained.

Dr Toppin says patients have a small window to choose their anaesthesiologists, and individuals tend to work with surgical teams. He said the public often does not know the critical role the anaesthesiologist plays in decisions about their surgeries.

“My job is to keep my patients comfortable; to monitor you throughout, from beginning to end; to keep all of that in mind and let the surgeons do what they need to do,” he told The Gleaner.