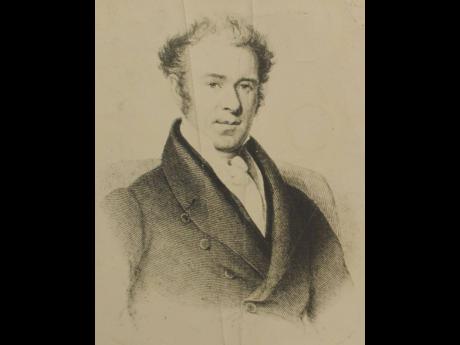

The detention and prosecution of Thomas Burchell

Baptist Reverend Thomas Burchell arrived in Jamaica from England in 1822 and quickly developed a deep hatred for slavery. He was instrumental in convincing the Baptist Missionary Society (BMS) and other social organisations to lobby the British Parliament to end slavery in its Caribbean colonies. He wrote several letters to the BMS criticising slavery, urging the organisation to join with the Society for the Abolition of Slavery in lobbying the British government to end slavery.

In 1827, one of Burchell’s letters was published in a popular British magazine and when news of the letter reached Jamaica, the local planters had Burchell arrested for treason. The planters offered to drop the charge if Burchell would make a public apology for his statements, but Burchell refused. The case was eventually discontinued, and Burchell earned folk-hero status among the enslaved for his firm antislavery stance. But, he could not imagine what fate had in store for him.

Sam Sharpe, an enslaved lay preacher, was a member of Burchell’s church. He was given much latitude to preach the gospel to other enslaved people. But, Sharpe was also secretly telling them that slavery was wrong, and he planned a general strike after the 1831 Christmas holidays if enslaved people were not paid from then on. However, somebody pre-empted Sharpe and lit the trash house at Kensington Estate in St James. This precipitated the 1831 Christmas Rebellion also called the Sam Sharpe/Baptist/Emancipation Rebellion.

Christian missionaries were blamed and persecuted for inspiring the uprising. Burchell was on his way back from a visit to England when the insurrection unfolded. Upon arriving in the country, he was ordered by the custos of St James not to leave the ship, Garland Grove. With him were his wife, their very young child, a missionary named Walter Dendy, and his wife. On February 9, Custos Richard Barrett ordered the release of Burchell as there was no evidence to incriminate him for helping to incite the rebellion.

But, when his detractors heard of his possible release and departure from Jamaica they went on the offensive again. They asked the custos to prevent him from leaving. But when that did not work, they trumped up a witness, Samuel Stennett, to say that he had heard Burchell encouraging the enslaved to riot and telling them that they had been given their freedom, which was being withheld.

As such, Burchell was taken from the ship and brought to the courthouse. He was detained until the next quarterly session. On the way to the court house a mob confronted him. Coloured people formed a shield around him until he reached the court house. Before the matter could reach the trial stage, things took a sudden turn.

It was reported that Stennett’s statement against Burchell was a big lie. He was bribed. Stennett officially retracted the statement and implicated magistrates and militiamen who had paid him to commit perjury. George Delisser, George McFarquhar Lawson Jr, Joseph Bowen and W. C. Morris, prominent men in town, Stennett claimed, were behind his lies.

“The former of whom assured him that he would be well looked upon by the gentleman of this place, that the country would give him £10 per annum, and that he, George Delisser, would make it £50. This deponent further said that he was induced to make this declaration to relieve his conscience, as he knew nothing about the said missionaries, and that he never joined the Baptist Society as a member until after Burchell had left the country. So help me God,” Stennett is quoted as saying in Lloyd A. Cooke’s book, The Story of the Jamaican Missions.

In court, Stennett did not back down. He looked the men into their eyes and reminded them of what they did. “You know that you did as I have stated, and you cannot deny it, and you, Mr Delisser, Mr Morris and Mr Bowen were the first persons that spoke to me about it and offered me money if I would do it,” Cooke quoted from Thomas Abbott’s letter, “about a narrative of certain events connected with the late disturbances in Jamaica, and the charges preferred against the Baptist missionaries in that island,” to the secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society.

The matter was subsequently dismissed, and Burchell was released on March 14, 1832. His persecutors were stunned, and a mob was once again up in arms against him. They assembled where he was accommodated, and he had to be guarded again by coloured men. On Chief Justice Tuckett’s advice he sought refuge on a ship, the Ariadne, for the night. The next day, with his family, he set sail for New York en route to England, effectively ending his missionary work in Jamaica.

Burchell went on to work with the anti-slavery movement, providing firsthand details of the atrocities of slavery. This information was heavily relied upon by members of the antislavery movement to gain the passage of the Emancipation Act of 1833.