Edward Seaga, Norman Manley and the defamation suits

Dr Dayton Campbell, general secretary of the People’s National Party (PNP), is facing three defamation lawsuits from individuals associated with the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP). Defamation lawsuits in Jamaica’s political arena are not uncommon....

Dr Dayton Campbell, general secretary of the People’s National Party (PNP), is facing three defamation lawsuits from individuals associated with the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP). Defamation lawsuits in Jamaica’s political arena are not uncommon. Throughout the decades, members of the major political parties have brought cases against each other. One of the earliest records of the mention of defamation lawsuits in post-Independence Jamaica’s political arena, involved a young rising political star, Edward Seaga, and the father of Jamaica’s Independence, Norman Manley.

It is fair to say that Seaga and Manley did not really get along. They respected each other, sure, but did they like each other - that is up for debate. However, in the beginning, there was admiration. In his autobiography, Edward Seaga, My Life and Leadership: Volume I: Clash of Ideologies, 1930-1980, Seaga stated that he first met Manley in 1955. As he recalled, “I was in the company of my friend, Dr M. G. ‘Mike’ Smith, who was paying a quick visit to Drumblair, Manley’s home and residential estate in uptown Kingston ... Manley arrived soon after Mike Smith and I got to Drumblair. He heard of my research in West Kingston and the promotion of Kapo ... We got into a discussion on Kapo’s art compared to Dunkley, the first Jamaican intuitive artist ... Manley’s image as an articulate man with a persuasive personality had preceded him; our brief discussion reinforced this.”

By the late 1950s, when Seaga became formally involved in Jamaican politics, he began writing commentary on Jamaican politics and development for The Gleaner. In that position, he gave “biting critiques” of the government’s dealings, the government now being headed by the PNP, where Manley was chief minister. Manley did not take these criticisms lightly and at one point told the press that Seaga was “a man with some pretensions to learning”. In one instance, Seaga wrote a letter to The Gleaner’s editor which was published on April 15, 1958. In it, he states, “I have no intention of trading emotional outbursts with the chief minister, Mr Norman Manley. I was not primarily concerned with whether the rumour I repeated in my article concerning contracts valuing £430,000 reported to be granted to the Charles Lopez Construction Co Ltd is true or false. Valid or not, it affected support for the PNP among much of the big-money sector of the business community and the alienation of this support was of importance to the articles. If Mr Manley sincerely believes that I have fabricated this rumour, it indicates to me that he is more than out of touch with the business world around him that I would have dared to imagine.”

Criticism and controversy

The next day, Manley issued a statement addressing the article to which he closed with the following as ‘shade’ to Seaga; “Finally, let me say that I do not at all object to comments and criticism of government activity. I believe that governments thrive on criticism and that controversy and debate are among the ways of maintaining a lively and alert public opinion. It happens that I like controversary and get great pleasure from it. I find, however, that many people who write for the press seem to think that criticism and controversy should be a one-sided affair. They like to criticise, but they are upset when they are answered. Critics should be made of sterner stuff.”

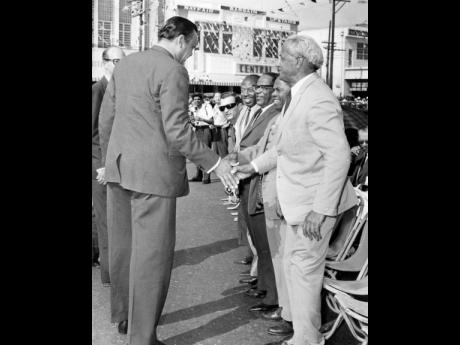

Safe to say, as Jamaica entered her post-Independence era and as both men stepped into new government roles, the political rivalry was still present. As Seaga details in his autobiography, these encounters with Manley “hardened my position and caused me to be even more scathing”. The rivalry between both men came to a head in October 1965, during the unveiling of Paul Bogle’s monument at Heroes Circle (then the George VI Memorial Park), as the country was celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Morant Bay Rebellion. Given that Bogle’s monument was done by Edna Manley, she arrived at the ceremony to which her husband, Norman, also was in attendance. In his book, N.W.Manley and the Making of Modern Jamaica, historian Arnold Bertram quotes Manley as saying, “I have come to the ceremony and my colleagues with me because we honour Paul Bogle”. And yet, Seaga insisted that Manley was to be removed from the VIP box, because he was not part of the official party even though his wife was in the VIP box. As history would have it, the crowd, which consisted of PNP supporters, was displeased and jeered Seaga on his actions towards Manley. In response, Seaga uttered a phrase that was said by Bogle during the 1865 rebellion. “Fire with fire, blood with blood and thunder with thunder.”

Taken out of its original context, the phrase has become a heavily quoted critique of Seaga’s contribution to the early days of Jamaica’s political violence, even though in all fairness he was quoting Bogle’s words at a ceremony to honour the man himself. As esteemed academic historian, Dr Matthew J. Smith states in his academic paper, ‘Rockstone: On Race, Politics and Public Memorials in Jamaica’, Seaga’s utterance was “words meant for colonial authorities but in the political atmosphere of independent Jamaica were read as inciting violence”. Still, the Bogle incident and the assumed violent threat would further strain the relationship between the young political protégé and the aging political vanguard. It also had a lasting effect on the Manley family. In her book, Drumblair: Memories of a Jamaican Childhood, Michael Manley’s daughter, Rachel, stated that “the incident had a profound effect on my father, who stated bluntly that he would never forget this insult to his father”.

Political violence

Almost a year later, Seaga made moves to file a lawsuit against Norman Manley. The situation surrounded a police raid that occurred at the West Kingston headquarters of both the JLP and PNP with the intention to curb the growing political violence in the constituency. In the middle of a state of emergency, law enforcement officers found suspicious materials at the JLP office. Soon after, Manley issued the following statement: “It is reported that a large number of revolvers and some homemade bombs and materials for making bombs and other instruments of violence including barbed wire bats have been found in the Western Kingston Headquarters of the Jamaica Labour Party”.

On October 5, 1966, Seaga issued the following statement, “On the basis of legal advice taken, I have instructed my solicitors to file writs against Mr. N. W. Manley... to recover damages for libel in connection with a statement issued by Mr Manley”. According to Seaga in his statement, only one bomb was found in his office (he was the member of parliament of the area at this time) and not any of the other materials mentioned by Manley.

Still, for publishing Manley’s statement, Seaga stated a similar defamation suit would be filed against The Gleaner Company Ltd and the Jamaica Broadcasting Commission (JBC). The next day, on October 6, The Gleaner carried the headline: ‘Libel Writ Filed Against RJR’. The article detailed that, on October 5, at 11:20 a.m., Seaga’s lawyer, George Fatta, filed a writ in the Supreme Court Registry claiming damages for alleged libel against RJR. Then, in an entirely new case, a month later in November 1966, Seaga filed defamation charges against JBC and another PNP member. This time, the defendant was Dudley Thompson, the man who would become his opponent in the MP race for Western Kingston in the February 1967 general election. The defamation suit concerned a statement made by Thompson on September 1, 1966, which JBC carried in a broadcast.

The legal events of 1966 obviously did not repair the strained relationship between Seaga and Norman Manley, and one could argue that the legal affairs between Seaga and Thompson played a small role in the explosion of political violence unleashed upon Western Kingston during the 1967 election.

Today, Jamaica and its political leaders must watch cautiously and ensure that the defamation suits against the current PNP general secretary do not have any lasting negative effects on the nation, including how both political parties are perceived by the electorate heading into the next general elections.

J.T. Davy is a member of the historical and political content collective, Tenement Yaad Media, where she co-produces their popular historical podcast, Lest We Forget. She is also a writer at the regional collective, Our Caribbean Figures. Send feedback to jordpilot@hotmail.com and editorial@gleanerjm.com.