Revivalism: A misunderstood folk religion – Part 4

Whither Revivalism?

THE PURPOSE of this series is to clarify the misconceptions that many Jamaicans have about Revivalism, a Jamaican folk religion that emerged from the Great Revival of 1860/1861. Revivalism is a confluence of African spirituality and European religiosity and is shrouded in symbolism. It has two main branches: Zion Revival, also known as 60; and Pocomania/Pukkumina, also known as 61.

By its very nature, Revival practices and rituals are very different from those of mainstream European religions despite the fact that elements of European religions are embedded within it. Some persons are wary and resentful of this difference, which could also be the basis of the plethora of myths, stigma, and taboos that are attached to it. The majority of the online feedback to the first three instalments was negative.

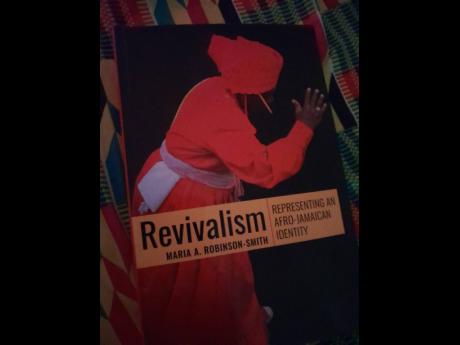

These responses are emblematic of the disdain that some Jamaicans still have for Revivalism, a religion that sprang from the souls of their African ancestors. To explain the forever contempt for Revivalism, Family and Religion turned to Revival research/scholar, Dr Maria A. Robinson-Smith, whose 2018 book, Revivalism – Representing an Afro-Jamaican Identity, evolved from her doctoral thesis.

She said, “...This thing is very deep in the psyche, that ‘nothing black is good’, that ‘anything African no good’, and anything you don’t understand is a myth, is obeah … The other thing is that our educational system did not address forms like Revivalism, how they sprung up, the value of them and where they originated. We have not looked at African religions. I remember when I was at school I learned all kind of things about Confucius and Buddha … I don’t remember learning anything about African religions … So a lot of it is ignorance and can only be addressed with education.

AMBIVALENT ATTITUDE

Much of the ignorance and resentment is perpetuated by some people in the non-Revival churches, who have always been wary and suspicious of Revival practices, but are entertained by staged performances of Revival ‘rituals’.

“In fact, nothing shows this more than the treatment of it in the annual national festival of Independence. In some of the festival entries, spirit possession and trumping are parodied, much to the sometimes embarrassed amusement of audiences,” Professor Barry Chevannes writes in his chapter,‘ Revivalism: A Disappearing Religion’,in the boo k, A Reader in African-Jamaican Music Dance Religion, edited by Markus Coester and Wolfgang Bender.

In his chapter, ‘ Revival Cults in Jamaica: Notes Towards a Sociology of Religion’, in the book, late Revival researcher and former prime minister of Jamaica, Edward Seaga, also addresses this factor.

“ The orthodox or accepted Christian churches in Jamaica have rarely, if ever, been able to come to terms with Revivalist cults. And naturally, Revivalists have found the cold formality of Christian orthodoxy, unsatisfactory. At the root of the whole problem lies the basic difference of religious thinking: on the one side, stands Christian monotheism, exclusive, guarded by a jealous God who condemns the worshippers of the Golden Calf and other idols.

“On the other side, there is African polytheism, all embracing and able to accommodate the Christian Trinity, the angels and saints, the prophets and apostles, combining these, however, with the spirit … The Christian Church in its orthodox, and accepted form, frowns upon the more emotional manifestations of the spirit,” Seaga writes.

It is also about colour and class as intimated by Seaga in the said chapter when he says, “ Revivalists are mostly outside the socio-economic framework of the middle class; membership is drawn primarily from the working class. The Christian middle class widely holds particular views of revivalists: pagan, superstitious, comical in ritual behaviour, tolerant of dishonesty. The suspicion of the practice of obeah (the use of spirits for destructive purposes) adds further to the middle class disrepute of cultists. The ambivalent attitude of the middle-class groups towards the African heritage contributes to the contempt.”

SIGNIFICANT SECTOR

The contempt is significant, and the aforementioned feedback to the first three instalments of this series is telling. Yet it seems like Revivalism is not leaving Jamaica’s religious landscape anytime soon.

The Zion Headquarters Jerusalem Spiritual Schoolroom is located in Watt Town, St Ann, to where three times a year Revival bands make pilgrimages in which Revival symbolic are on full display.

Robinson Smith said:“When you go to Watt Town … just look at the groups that are coming from all across the island. And look at the age groups, (which) span generations, up to baby. When you see three-year-olds, and so, when you put them down and they rock to the rhythm, you know it’s in their blood. The young people - so many young people are in it now. It’s really not going anywhere. It’s here to stay. A lot of young people are in it, that is what tells you that the religion is here to stay.”

Robinson-Smith, a former associate/’student’ of Edward Seaga, concludes her book:

“It is the Revival iconography that sets Revivalism apart from all other religions and cultural forms and gives it legitimacy as an African-Jamaican phenomenon. The seals and symbols, the iconic spaces, rituals and ceremonies, colour codes, dress, accessories, music, and dances are all part of a body of knowledge that guards the African legacy, echoes the people’s worldview and provide the signifier performance of an African Jamaican identity.”

In the foreword, Seaga says, inter alia, “T he following points made by the author must be underscored: the seals, symbols, iconic spaces, rituals and ceremonies, colour codes and accessories are part of a system of knowledge with shared meanings among Revivalists and African Jamaicans across Jamaica and beyond. This system of knowledge also guards and reinvents the African legacy that is very real to Revivalists.”

In his chapter, ‘ Revival Cults in Jamaica: Notes Towards a Sociology of Religion’, Seaga also says, “ No doubt, both Zion and Pukkumina offer their followers a spiritual, social, and, at times, economic aid, which is to them available in an acceptable and satisfying form. It remains to be seen whether the forces of social and economic change will either modify or obliterate the Revival practices of a significant sector of the Jamaican population.”