Alexander Bedward a complex folk hero

JAMAICA’S HISTORY and heritage are replete with notable men and women, some of whom had been elevated to the status of national hero, the highest national honour in the land. Others have been colourful folk heroes and heroines, from the people and of the people. Alexander Bedward (1859-1930) was one of such folk heroes, and he was as complex and colourful as they could possibly get.

Born to peasant parents, he worked for a while on the Mona Estate near August Town. Times were hard and like thousands other Jamaicans he went to Colon in Panama in the 1880s to work on the Panama Canal. It could have been because of the dreadful working conditions in Colon why he returned home, yet, Olive Senior, in Encyclopedia of Jamaican Heritage, has another explanation.

“While in Colon, Bedward had a vision or ‘religious crisis’ that made him return home,” she writes. At home there was a “remarkable prophet” named H.E.S. Woods, also called ‘Shakespeare’, who had established the Jamaica Native Baptist Free Church in August Town. He converted and baptised Bedward, and predicted that a movement led by a charismatic leader would emerge from the elders in his church.

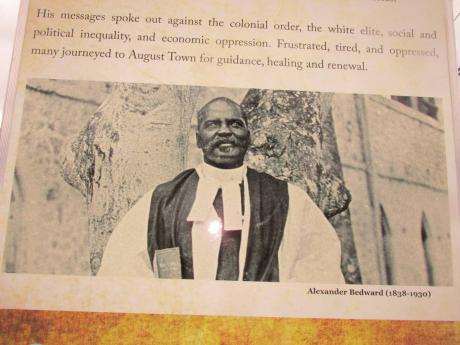

It now seems like Bedward was that leader. At the beginning of the 1890s he became very active in Woods’ church. It was a refuge and home to many, an escape from European religiosity from which the laity felt disconnected and did not trust. The established Church and the government themselves did not trust what Bedward and his followers were doing, and so they got antsy and kept a close watch on them. For, it was not all about religion and spirituality. Politics, too, was in the mix.

In 1895 Bedward was arrested for sedition because he prophesied that “the black wall will crush the white wall”. It is said that he also mentioned the Morant Bay Uprising of 1865. He was declared insane and committed to a lunatics’ asylum. His sojourn there was short-lived as he was well defended by his lawyers.

For the next 26 years Bedwardism thrived at August Town. In 1901, the same year when Woods died, he had made Bedward a bishop, and gave him the title of ‘shepherd’. Affiliated camps were set up in other parts of the island. Bedward fast became known as a faith healer, who was “called by God”. His preaching was rivetting, pulling people from all over the island to his camp at August Town, which included a church, beside the Hope River – the ‘healing stream’ – into which converts were baptised.

“Bedwardism taught obedience as its foundation principle. Of the ‘three heavens’ prepared for the believer, the first one was to be gained through blood, the second through love, the third through obedience to the teachings of Bedward. Much, in these teachings, emphasised the Holy Ghost as the third revelation of the Trinity,” Martha Warren Beckwith writes in A Reader in African-Jamaican Music Dance Religion, edited by Markus Coester and Wolfgang Bender. There was much focus on a special purification ceremony before baptism and on a voluntary three-day fast after baptism.

At the beginning of the 1920s, Bedward had predicted his ascent to Heaven, the destruction of white people, and the rule of Bedwardism on Earth. People were encouraged to relocate to the camp, which would be the only safe place to be when the predictions came to pass. He said he would go to Heaven on December 31, 1920 and return on January 3, 1921. That ascent and descent did not manifest; Bedward said the time was not right, and kept giving new dates.

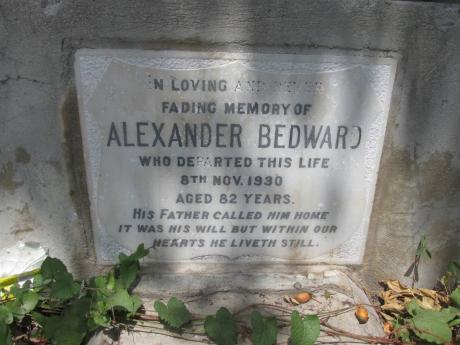

Perhaps April 21, 1921 was the right time; it was the day when he and his followers started a march to Half-Way Tree. Police and soldiers, waiting for the time, curtailed the march and arrested Bedward and over 600 members of his flock. They were charged under the Vagrancy Law. Some were jailed immediately; others were remanded to return for trial. Bedward, their charismatic shepherd,was locked up in the lunatics’ asylum where he died on November 8, 1930.

“Far from being, as the scoffers say, a scheming pretender fattening up on the credulity of his followers, he was himself the most duped among them. He was a dreamer, now so far gone in senility, he must have been about 62 years of age, as to have dreamed the impossible,” Martha Warren Beckwith, who interviewed Bedward in December 1920, writes.

Influential, powerful, iconic, delusional perhaps, Alexander Bedward’s place in Jamaica’s social and religious history is a checkered, complex and celebrated one, indelible. He has inspired folk and pop culture, is the subject of academic papers, and has put Hope River and August Town on the world map. He had furnished many answers to some people’s ontological questions, and had provided a space where they could freely express themselves and fulfil their spiritual needs.

In Bedward they saw themselves and what they could possibly be. He was an unapologetic rebel with a cause, and the Bedwardites supported, and followed him all the way to jail and the madhouse. For he was Bedward, the man for all reasons, their healer at a time when colonial ethos and sensibilities were mainly concerned with Christianising them, yet creating social barriers, and disregarding their spiritual needs.

The folk song, “Dip them Bedward, dip dem/Dip dem in de healing stream/Dip dem sweet but not too deep/Dip dem fe cure bad feeling,” is telling.

“I was also privileged to be able to sit and listen to the most fascinating stories about Alexander Bedward from a number of people, one of whom was my grandfather, Earnest Gordon, a Baptist deacon. He had travelled from St Ann to Kingston with scores of other people to be baptised by Bedward … I knew by the expression on their faces and the fervour with which they spoke, that these events meant much to them and that in recounting and retelling the stories they were affirming their significance,” Maria A. Robinson-Smith writes in her book, Revivalism Representing An Afro-Jamaican Identity.